British soldiers in the eighteenth century

This was in part a reaction to the constant gambling, whoring, drinking, and brawling that British soldiers participated in due to a variety of reasons.

[1] Camp life was dirty and cramped with the potential for a rapid spread of disease,[2] and punishments could be anything from a flogging to a death sentence.

Yet, many men volunteered to join the army, to escape the bleak conditions of life in the cities, for a chance to travel the world and earn a regular wage.

[9] Certainly more applicable to the landed and wealthy gentlemen, fears of invasion also persuaded many to serve;[10] not so much to support the nation as a whole, but to preserve their own interests, money and property which could be lost if the enemy succeeded.

[12] John Cookson suggests that serving with the army did command a certain respect, and those men that became the holder of an office "could lay claim to the title of [being a] gentleman".

[21] There was much that could go wrong with the musket – from misfires in wet weather, to the gun firing at random due to sparks which set the powder off.

[25] A traditional regiment of foot, made up of ten companies of approximately 792 men, would have carried a set of camp equipment that included 160 tents, 160 tin kettles with bags, 160 hand hatchets, 12 bell tents, 12 camp colours, 20 drum cases, 10 powder bags, 792 water flasks with strings, 792 haversacks and 792 knapsacks.

The courts – either regimental, district or general – were advised by a military lawyer and made up of panels of officers, with some sentences even being determined by the commander-in-chief.

The camp followers were usually subject to the same military law as the men themselves: a sutler could be flogged or even killed if found to be trading without a licence, and common offences included stealing and disobeying of direct orders.

Soldiers received a daily wage after their sign up bounty, though once equipment and food had been purchased, they were left with little in the way of luxuries.

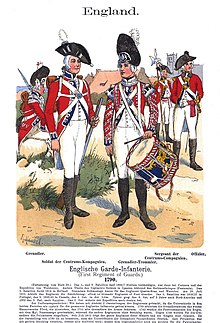

[42] When marching into war a soldier would have worn the traditional red uniform consisting of the distinctive regimental coat, a white shirt, grey trousers to be held up by a pair of braces, shoes and a cap.

[44] A greatcoat, fashioned in grey wool, would be worn and was normally tied on top of the haversack or knapsack which was carried by the men while on the move.

[45] The chance to wear something as distinctive as the regimental red could be extremely tempting; a new and vivid uniform would have been a welcome change from the drab colours worn by most men in everyday society and soldiers frequently drew interest from admiring women.

[44] This uniform was much lighter than the one worn for war, being made from linen and the caps from wool, and therefore allowing the men to work in comfort during encampment.

Officers wore one shoulder belt which often supported a sabre scabbard or pistol cartridge box, since they did not carry a musket.

When on campaign, soldiers would normally be supplied with an allowance of bread, meat, oatmeal or rice and either beer or rum to wash it down with.

[51] Stews and meat pies were regularly cooked and small beer – for which a man received around 5 pints per diem – and rum were watered down in order to last and deter the men from drunken behaviour.

[52] Small beer was often brewed to kill any germs that was present in the water, and was one way in which to reduce the spread and rates of disease.

Vegetables were also grown and livestock procured to help feed the troops, but there were many reports of soldiers sickening due to a lack of proper nourishment.

[54] The level to which troops were adequately fed varied, being dependent on the nature of the terrain the army was operating in and on the skill of their senior commanders.

A loaf of bread usually cost around 5d, while a dragoon soldier, earning 1s 6d daily, would have paid 6d for a ration of forage consisting of 18 lb (8 kg) of hay and one peck (16 dry pints) of oats.

Considering the prices of camp necessaries during this period, many items cost a few shillings: a haversack could be purchased for 3s 6d while leather powder bags could be found for 7s.

[63] Patriotic parades and celebrations often included regular army units, the militia or local volunteer regiments, and were an important component of civic ceremony and pride.

[64] The public perception of the British Army gradually changed as the long war with Revolutionary/Imperial France wore on, contributing to the Duke of York's structural, recruitment and training reforms in the early 1800s.