Prehistory of Transylvania

We can assume that in Transylvania, alongside mammoths or deer, horses were a fairly important food source, if our dating of the painting on the ceiling of the cave at Cuciulat, Sălaj County, is correct.

The same cannot be said about the discoveries in the Ciuc Depression [ro] at Sândominic, Harghita County, where several tools, and a rich fauna, have been encountered in certified stratigraphic positions, belonging to the geo-chronological interval covering the late Mindel to the early Riss.

Northwestern Transylvania is the site where layers of the Middle Aurignacian culture have been identified, as signaled by the presence of blade scrapers, refitted core, [clarification needed] burins.

In Banat, the settlements of Tincova, Coșava, and Românești-Dumbrăvița, have produced flint tools demonstrating that the Aurignacian in this area evolved closely with that in Central Europe (the Krems-Dufour group).

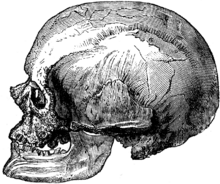

The Climente II cave has produced a human skeleton, set in a crouching position, and covered by a thick layer of red ochre, which is attributed to the Tardigravettian dwelling and which predates Level I at Cuina Turcului.

The Tardenoisian spread in several of the country's regions (Moldavia, Muntenia, Dobruja), including the mountainous area of Transylvania in the southeast (Cremenea-Sita Buzăului, Costanța-Lădăuți) and northwest (Ciumești-Pășune).

In the settlement of Ciumești, Satu Mare County, besides the typically Central and East European Tardenoisian microlitice tools made of flint and obsidian, some artefacts were found in the form of circular segments and two triangular ones, in addition to trapezes.

Some specialists do not exclude the possibility of identifying the Late Tardenoisian communities of the north-western Pontic or central European types (of which the settlement at Ciumești is one) as being in the process of neolithization, albeit incomplete, that is, displaying an incipient productive economy, whose foundations were laid by animal domestication and plant cultures.

Consequently, the process of neolithisation, which is essentially a shift to plant growing and animal breeding, was not an innovation of the local Mesolithic population but rather the result of the penetration of this territory by communities carrying the Neolithic civilization.

The small number of sites attributable to this early cultural time has not allowed the route followed by the group, to penetrate the Inter-Carpathian area, to be firmly established, yet in all likelihood, it was the Olt Valley.

At Ocna Sibiului, at Precriș, level II, a small conical stone statuette was found, with a shape representing a couple embracing, and a plinth of the same material associated with the figure.

The Parța settlement, thoroughly researched, demonstrates that the culture reached a high level of civilization, attested to by the one storey buildings and by a complex spiritual life, partly decoded by the components of the great sanctuary studied here.

The preservation by some Starčevo-Criș communities of painted pottery, in addition to the Vinča elements, engendered[clarification needed] in the area of the eastern arch of the Western Carpathians the Cluj–Cheile Turzii–Lumea Nouă–Iclod cultural complex.

The presence of red ochre scattered over the skeletons, or laid at their feet in the form of little balls, as well as other ritual elements find better analogies, however, in the necropolis at Mariupol in south Ukraine.

The role of the invasion of the pastoral tribes coming from the north-Pontic (supposedly Indo-European kinship) in bringing to an end the Eneolithic culture of sedentary farmers, represents one of the hotly debated issues among specialists in the prehistory of south-eastern Europe.

As communities acquired the secrets of alloying brass and arsenic, tin, zinc, or lead, achieving the first items in bronze, the long period during which stone constituted the main raw material for fashioning implements and weapons was coming to an end.

For the first, the most typical is the Baden–Coțofeni cultural bloc, which perpetuated in many aspects a transitory lifestyle, but evolved in parallel to the pre-Schneckenberg and Schneckenberg civilisations, which were more active in taking over[clarification needed] the products of the Aegean-Anatolian Early Bronze.

Non-ferrous metallurgy in Early Bronze Age, given the substantial fall in production as compared to the Eneolithic, should be regarded as undergoing some sort of realignment, or repositioning, rather than indicating an acute decline.

Most remarkable in this context were the super-elevated handles, shaped into ram heads, of a large size receptacle found south of the Carpathians, at Sărata Monteoru, Buzău County.

The importance of the settlements, as a constructed and limited human space for the prehistoric population, is graphically suggested by Mircea Eliade,[citation needed] when he interprets them as symbolic of the "centre of the world".

The analyzed archeological sites evolved from simple groupings of lodges to complex urban facilities, directed towards maintaining collective lifestyle quality, ensuring the protection of life and goods, and meeting specific social, economic, defense and cultic needs.

In settlements belonging to the classical period of the Bronze Age were found charred seeds, numerous farming implements, grinding mills of diverse types, all attesting the intensive cultivation of grains.

It portrayed implements (pickaxe and basket), whose absolutely sensational analogs were found in the photos of miners, taken by B. Roman at the middle of the last[clarification needed] century, strongly suggesting that the mining of non-ferrous metals was also performed underground.

[clarification needed] The mass of the ethnographic data which associates the ground with the belly, the mine with the womb, and the ore with the embryo, speaks of the sexuality of the mineral realm, and of the blacksmith's belongings and implements.

Cultic practices were performed by the people of the Bronze Age in diverse locations: in mountains, trees, springs, rivers, clearings or even, as noted, in specially assigned places inside the settlements.

The divinities guarding this space were in harmony with the weapons, ornaments or gifts personal or social in nature (grains, plants, food), with the animal, even human, sacrifices, with ceramics and bone, as well as with gold, silver or bronze.

The repeated occurrence of the solar motifs covering the walls of the receptacles deposited, typically masculine, might be speaking of the joining of the two spheres: earth-sun, female-male, immobile-mobile, thus demonstrating the dualism of creeds in the Bronze Age.

In the same era, the metals produced on the slopes of the eastern arch of the Western Carpathians arrived in different ways in distant places all over Europe; so did the salt Transylvania is so rich in.

The arguments in favour are strong: long periods of peaceful development, the location of the deposits (confluence of rivers, lakes, springs, clearings, mild slopes looking east, etc.

Finally, besides some such crafts as metallurgy which imply special skill, members of every family engaged in a series of activities such as weaving, spinning, and leather dressing, shown by the discovery in the dwellings of spindle, spools, sewing needles, and scrapers for cleaning hide.