Battle of Broodseinde

After the period of unsettled but drier weather in September, heavy rain began again on 4 October and affected the remainder of the campaign, working more to the advantage of the German defenders, being pushed back on to far less damaged ground.

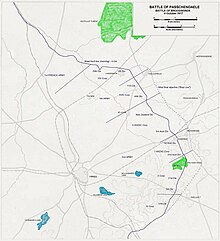

At the Battle of Poelcappelle on 9 October, after several more days of rain, the German defence achieved a costly success, holding the approaches to Passchendaele village, the most tactically important ground on the battlefield.

Haig wanted XV Corps on the Belgian coast and the amphibious force of Operation Hush readied, in case of a general withdrawal by the Germans.

Gough and Plumer replied over the next couple of days, that they felt that the proposals were premature and that exploitation would not be feasible until Passchendaele ridge had been captured as far north as Westroosebeke.

[3] The British tactical refinements had sought to undermine the German defence-in-depth, by limiting objectives to a shallower penetration and then fighting the principal battle against Eingreif divisions as they counter-attacked, rather than against the local defenders.

[5] When the Germans counter-attacked, they encountered a reciprocal defence-in-depth, protected by a mass of artillery like the British green and black lines on 31 July and suffered many casualties to little effect.

[3] The Battle of the Menin Road Ridge on 20 September, was the first attack with the more limited territorial objectives developed since 31 July, to benefit from the artillery reinforcements brought into the Second Army area and a pause of three weeks for preparation, during which the clouds dispersed and the sun began to dry the ground.

[6] The shorter intervals between attacks since then had several effects, allowing less time for either side to prepare and the Germans had to take more risks on the rest of the Western Front, to replace tired and depleted divisions in Flanders.

[26] Operation High Storm (Unternehmen Höhensturm), a bigger German methodical counter-attack, intended to recapture the area around Zonnebeke which had been planned for 3 October, was postponed for a day.

German troops counter-attacked eight times and regained Polderhoek Spur, leaving the new front line along the west of Cameron Covert and just short of Château Wood.

Massed small-arms fire from the Polderhoek spur caused many casualties in the 64th Brigade on the right, which withdrew slightly to sheltered ground, without sacrificing the commanding position which protected the right flank of the Anzac Corps further north.

The left brigade picked its way through marshy ground and tree stumps in Romulus and Remus Woods, north of Molenaarelsthoek and then outflanked a group of blockhouses, some troops crossing into the 2nd Australian Division area.

At 8:10 a.m. the advance resumed to the final objective (blue line) which was consolidated and outposts established in front of it, despite long-range fire from the Keiberg spur and a small rise north east of Broodseinde village.

The Australian troops began to fire on the move and destroyed the first German wave, at which those to the rear retreated back into the British creeping barrage, while others retired in stages through Zonnebeke.

[39] The leading battalion of the 10th Brigade on the left had edged so far forward that when the advance began, it was 30 yd (27 m) from the pillboxes at Levi Cottages at the top of the rise, beyond which was a dip then the slope of Gravenstafel ridge.

After a twelve-minute pause at this (first intermediate) objective, to give the New Zealanders on the left time to cross the boggy ground in their area, the two following battalions leapfrogged through, that of the right brigade taking many German prisoners from dug-outs along the railway embankment and reaching the red line quickly.

After a delay caused by the British bombardment dwelling for nearly half an hour, the left brigade advanced up Gravenstafel Spur and then pressed on to silence several machine-guns in pillboxes on Abraham Heights.

[40] At 8:10 a.m. the advance resumed and after a pause to capture Seine pillbox, the right brigade crossed Flandern I Stellung, which lay diagonally across its path and reached the final objective.

Fire from the Winzig, Albatross Farm and Winchester blockhouses, in the 48th (South Midland) Division area further north (and from the Bellevue spur up the Stroombeek valley), delayed the advance until they were captured.

The advance to the final objective, between Flandern I Stellung where it met the Ypres–Roulers railway, north to Kronprinz Farm on the Stroombeek began and a German battalion headquarters was captured in the Waterloo pillboxes.

Fire from the church and the Brewery pillbox in Poelcappelle caused a delay but Gloster Farm was captured with the aid of two tanks and the red line (first objective) consolidated.

A gap on the boundary with the 29th Division to the north was filled as dark fell and German infantry assembling for a counter-attack were spotted and dispersed by artillery fire.

[48] Unternehmen Höhensturm, (Operation High Storm) a methodical counter-attack (Gegenangriff) planned for 4 October, was intended to recapture as much of the ridge on Groote Molen (Tokio) spur as possible.

[54] The capture of the ridges was a great success and Plumer called the attack "... the greatest victory since the Marne" and Der Weltkrieg, the German official history, referred to "... the black day of October 4".

[56] The X Corps divisions had managed to take most of their objectives about 700 yd (640 m) forward, gaining observation over the Reutelbeek valley but had relinquished ground in some exposed areas.

[58] Wet ground had caused some units to lag behind the creeping barrage, as well as reducing the effect of shells, many landing in mud and being smothered, although this affected German artillery equally.

In his diary entry for 4 October, Rupprecht wrote that the British advance had lengthened the front, which made the defence more difficult and that a counter-attack from Becelaere and Gheluvelt was necessary.

[62] In 2018, Jonathan Boff wrote that after the war the Reichsarchiv official historians, many of whom were former staff officers, ascribed the tactical changes in the wake of the defeat of 26 September and their reversal after the Battle of Broodseinde on 4 October, to Loßberg.

The other German commanders were exculpated and a false impression created that OHL operated in a rational manner, when Ludendorff imposed another defensive scheme on 7 October.

On 2 October, Rupprecht ordered the 4th Army HQ to avoid over-centralising command only to find that Loßberg had issued an artillery plan detailing the deployment of individual batteries.