Bucareli Treaty

[6][7] The treaty sought to channel the demands of U.S. citizens for alleged damage to their property caused by internal wars of the Mexican Revolution from 1910 to 1921.

Part of the relative weakness of President Álvaro Obregón's government came from the fact that the United States had not recognized the postrevolutionary regime.

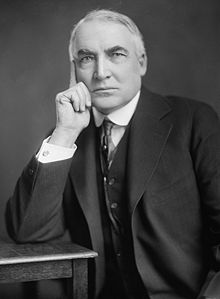

[11] The 1917 Mexican Constitution, with its strong socialist and nationalist influence, had hurt many U.S. interests,[4] which made U.S. President Warren G. Harding refuse to recognize Obregón as legitimate.

The U.S. also demanded the repeal of several articles of the Mexican Constitution of 1917 or at least their exemption for the U.S.[3] For Obregón, U.S. recognition of his government was a priority to avoid the constant threat of war.

[10] The low-profile negotiations that led to the treaty took place from May to August 1923 at the Secretariat of the Interior building on Avenida Bucareli, in Mexico City.

In regards to the absence of further discussion in the American Senate, we could conclude that the entire Bucareli Treaty was technically approved, if not in a strict sense of legislative ratification.

Robles also recalled no discussion of the General Conventions in the Senate beyond straight approval, and he believed the agreement was too personal to represent the Mexican government.

[25] Overall, the undemocratic way of approval, the lack of negotiations in the cabinet, along with the bloody measures, was ultimately not only undesirable but also detrimental to the legitimacy of the treaty, even the administration itself.

The former interim president, Adolfo de la Huerta, who was in Obregon's cabinet as Secretary of the Treasury, asserted that the treaty violated the national sovereignty and subjected Mexico to humiliating conditions.

De la Huerta resigned and moved to Veracruz, where he launched a manifesto that set off the Delahuertista rebellion in December 1923.

[26] It has been argued that from 1910 to 1930, civil wars, military coups, and rebellions devastated the industries in Mexico and stopped higher education, research, and technological development and that the social and political instability also drove off the foreign investments.

[citation needed] When Plutarco Elías Calles took office on December 1, 1924, one of the main points of contention between the United States and Mexico remained oil.

[29] After that, Calles quickly rejected the Bucareli Treaty and began drafting a new oil law that strictly fulfilled Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution.