The Buddha

His given name, "Siddhārtha" (the Sanskrit form; the Pali rendering is "Siddhattha"; in Tibetan it is "Don grub"; in Chinese "Xidaduo"; in Japanese "Shiddatta/Shittatta"; in Korean "Siltalta") means "He Who Achieves His Goal".

[31] A list of other epithets is commonly seen together in canonical texts and depicts some of his perfected qualities:[32] The Pali Canon also contains numerous other titles and epithets for the Buddha, including: All-seeing, All-transcending sage, Bull among men, The Caravan leader, Dispeller of darkness, The Eye, Foremost of charioteers, Foremost of those who can cross, King of the Dharma (Dharmaraja), Kinsman of the Sun, Helper of the World (Lokanatha), Lion (Siha), Lord of the Dhamma, Of excellent wisdom (Varapañña), Radiant One, Torchbearer of mankind, Unsurpassed doctor and surgeon, Victor in battle, and Wielder of power.

It was also the age of influential thinkers like Mahavira,[90] Pūraṇa Kassapa, Makkhali Gosāla, Ajita Kesakambalī, Pakudha Kaccāyana, and Sañjaya Belaṭṭhaputta, as recorded in Samaññaphala Sutta, with whose viewpoints the Buddha must have been acquainted.

These texts contain descriptions of the culture and daily life of ancient India which can be corroborated from the Jain scriptures, and make the Buddha's time the earliest period in Indian history for which significant accounts exist.

[116] Legendary biographies like the Pali Buddhavaṃsa and the Sanskrit Jātakamālā depict the Buddha's (referred to as "bodhisattva" before his awakening) career as spanning hundreds of lifetimes before his last birth as Gautama.

"[134] According to later biographies such as the Mahavastu and the Lalitavistara, his mother, Maya (Māyādevī), Suddhodana's wife, was a princess from Devdaha, the ancient capital of the Koliya Kingdom (what is now the Rupandehi District of Nepal).

The earliest Buddhist sources state that the Buddha was born to an aristocratic Kshatriya (Pali: khattiya) family called Gotama (Sanskrit: Gautama), who were part of the Shakyas, a tribe of rice-farmers living near the modern border of India and Nepal.

[156] While the earliest sources merely depict Gotama seeking a higher spiritual goal and becoming an ascetic or śramaṇa after being disillusioned with lay life, the later legendary biographies tell a more elaborate dramatic story about how he became a mendicant.

[177] According to the legendary biographies, when the ascetic Gautama first went to Rajagaha (present-day Rajgir) to beg for alms in the streets, King Bimbisara of Magadha learned of his quest, and offered him a share of his kingdom.

[184][185] Gautama felt unsatisfied by the practice because it "does not lead to revulsion, to dispassion, to cessation, to calm, to knowledge, to awakening, to Nibbana", and moved on to become a student of Udraka Rāmaputra (Pali: Udaka Ramaputta).

[203] The Pali texts also report that he continued to meditate and contemplated various aspects of the Dharma while living by the River Nairañjanā, such as Dependent Origination, the Five Spiritual Faculties and suffering (dukkha).

[u] Various sources such as the Mahāvastu, the Mahākhandhaka of the Theravāda Vinaya and the Catusparisat-sūtra also mention that the Buddha taught them his second discourse, about the characteristic of "not-self" (Anātmalakṣaṇa Sūtra), at this time[212] or five days later.

[209] The Theravāda Vinaya and the Catusparisat-sūtra also speak of the conversion of Yasa, a local guild master, and his friends and family, who were some of the first laypersons to be converted and to enter the Buddhist community.

[213][209] The conversion of three brothers named Kassapa followed, who brought with them five hundred converts who had previously been "matted hair ascetics", and whose spiritual practice was related to fire sacrifices.

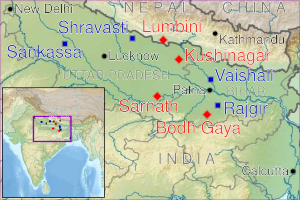

[217][209] For the remaining 40 or 45 years of his life, the Buddha is said to have travelled in the Gangetic Plain, in what is now Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and southern Nepal, teaching a diverse range of people: from nobles to servants, ascetics and householders, murderers such as Angulimala, and cannibals such as Alavaka.

The early texts tell the story of how the Buddha's chief disciples, Sāriputta and Mahāmoggallāna, who were both students of the skeptic sramana Sañjaya Belaṭṭhiputta, were converted by Assaji.

The Buddha is eventually convinced by Ānanda to grant ordination to Mahāprajāpatī on her acceptance of eight conditions called gurudharmas which focus on the relationship between the new order of nuns and the monks.

Early sources speak of how the Buddha's cousin, Devadatta, attempted to take over leadership of the order and then left the sangha with several Buddhist monks and formed a rival sect.

The Sthavira texts generally focus on "five points" which are seen as excessive ascetic practices, while the Mahāsaṅghika Vinaya speaks of a more comprehensive disagreement, which has Devadatta alter the discourses as well as monastic discipline.

The Buddha says that the Sangha will prosper as long as they "hold regular and frequent assemblies, meet in harmony, do not change the rules of training, honour their superiors who were ordained before them, do not fall prey to worldly desires, remain devoted to forest hermitages, and preserve their personal mindfulness".

[273] A number of teachings and practices are deemed essential to Buddhism, including: the samyojana (fetters, chains or bounds), that is, the sankharas ("formations"), the kleshas (unwholesome mental states), including the three poisons, and the āsavas ("influx, canker"), that perpetuate saṃsāra, the repeated cycle of becoming; the six sense bases and the five aggregates, which describe the process from sense contact to consciousness which lead to this bondage to saṃsāra; dependent origination, which describes this process, and its reversal, in detail; and the Middle Way, summarized by the later tradition in the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path, which prescribes how this bondage can be reversed.

[276] All beings have deeply entrenched samyojana (fetters, chains or bounds), that is, the sankharas ("formations"), kleshas (unwholesome mental states), including the three poisons, and āsavas ("influx, canker"), that perpetuate saṃsāra, the repeated cycle of becoming and rebirth.

It is the unsatisfactoriness and unease that comes with a life dictated by automatic responses and habituated selfishness,[280][281] and the unsatifacories of expecting enduring happiness from things which are impermanent, unstable and thus unreliable.

[280]In numerous early texts, this basic principle is expanded with a list of phenomena that are said to be conditionally dependent,[295][ab] as a result of later elaborations,[296][297][298][ac] including Vedic cosmogenies as the basis for the first four links.

[338] According to Richard Gombrich, the Buddha's teachings on Karma and Rebirth are a development of pre-Buddhist themes that can be found in Jain and Brahmanical sources, like the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad.

[339] Likewise, samsara, the idea that we are trapped in cycles of rebirth and that we should seek liberation from them through non-harming (ahimsa) and spiritual practices, pre-dates the Buddha and was likely taught in early Jainism.

He posits that the Fourth Noble Truths, the Eightfold path and Dependent Origination, which are commonly seen as essential to Buddhism, are later formulations which form part of the explanatory framework of this "liberating insight".

[aq] The Buddha also critiqued the Brahmins' claims of superior birth and the idea that different castes and bloodlines were inherently pure or impure, noble or ignoble.

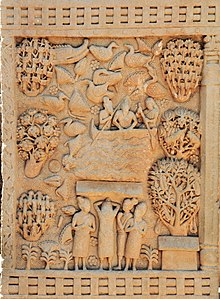

During this early aniconic period, the Buddha is depicted by other objects or symbols, such as an empty throne, a riderless horse, footprints, a Dharma wheel or a Bodhi tree.

[424] Other styles of Indian Buddhist art depict the Buddha in human form, either standing, sitting crossed legged (often in the Lotus Pose) or lying down on one side.