Sacred bull

The Sumerian guardian deity called lamassu was depicted as hybrids with bodies of either winged bulls or lions and heads of human males.

"The human-headed winged bulls protective genies called shedu or lamassu, ... were placed as guardians at certain gates or doorways of the city and the palace.

Fill Gilgamesh, I say, with arrogance to his destruction; but if you refuse to give me the Bull of Heaven I will break in the doors of hell and smash the bolts; there will be a confusion of people, those above with those from the lower depths.

When they reached the gates of Uruk the Bull of Heaven went to the river; with his first snort cracks opened in the earth and a hundred young men fell down to death.

With his third snort cracks opened, Enkidu doubled over but instantly recovered, he dodged aside and leapt onto the Bull and seized it by the horns.

A long succession of ritually perfect bulls were identified by the god's priests, housed in the temple for their lifetime, then embalmed and buried.

[5] We cannot recreate a specific context for the bull skulls with horns (bucrania) preserved in an 8th millennium BCE sanctuary at Çatalhöyük in Central Anatolia.

One of these is Gavaevodata, which is the Avestan name of a hermaphroditic "uniquely created (-aevo.data) cow (gav-)", one of Ahura Mazda's six primordial material creations that becomes the mythological progenitor of all beneficent animal life.

In medieval times, Hadhayans also came to be known as Srīsōk (Avestan *Thrisaok, "three burning places"), which derives from a legend in which three "Great Fires" were collected on the creature's back.

— Atri and the Last Sun "He the mighty bull who with his seven reins let loose the seven rivers to flow, who with his thunderbolt in his hand hurled down Ruhina as he was climbing up to the sky, he my people is Indra."

The humpbacked Zebu bull (bos indicus) appears on the coinage of the Indian subcontinent from the Iron Age to the modern day.

Bull symbols appear regularly on silver karshapana, or punchmarked coins, first issued by the Janapada kingdoms, and continued by the Magadhan and Mauryan empires.

[9] Kushan empire (c.30-275 CE) coins and those of the Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom (230-365) depict the Iranian god Wēś beside a bull, sometimes holding a trident and beside a Nandipada symbol.

[18] Exodus 32:4[19] reads "He took this from their hand, and fashioned it with a graving tool and made it into a molten calf; and they said, 'This is your god, O Israel, who brought you up from the land of Egypt'."

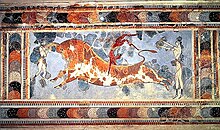

Zeus took over the earlier roles, and, in the form of a bull that came forth from the sea, abducted the high-born Phoenician Europa and brought her, significantly, to Crete.

Minotaur was fabled to be born of the Queen and a bull, bringing the king to build the labyrinth to hide his family's shame.

In the Classical period of Greece, the bull and other animals identified with deities were separated as their agalma, a kind of heraldic show-piece that concretely signified their numinous presence.

The religious practices of the Roman Empire of the 2nd to 4th centuries included the taurobolium, in which a bull was sacrificed for the well-being of the people and the state.

Public taurobolia, enlisting the benevolence of Magna Mater on behalf of the emperor, became common in Italy and Gaul, Hispania and Africa.

In the so-called "tauroctony" artwork of that cult (cultus), and which appears in all its temples, the god Mithras is seen to slay a sacrificial bull.

Although there has been a great deal of speculation on the subject, the myth (i.e. the "mystery", the understanding of which was the basis of the cult) that the scene was intended to represent remains unknown.

[26] Tarvos Trigaranus (the "bull with three cranes") is pictured on ancient Gaulish reliefs alongside images of gods, such as in the cathedrals at Trier and at Notre Dame de Paris.

In Irish mythology, the Donn Cuailnge and the Finnbhennach are prized bulls that play a central role in the epic Táin Bó Cúailnge ("The Cattle Raid of Cooley").

… Mistletoe is rare and when found it is gathered with great ceremony, and particularly on the sixth day of the moon….Hailing the moon in a native word that means 'healing all things,' they prepare a ritual sacrifice and banquet beneath a tree and bring up two white bulls, whose horns are bound for the first time on this occasion.

[30] The practice of bullfighting in the Iberian Peninsula and southern France are connected with the legends of Saturnin of Toulouse and his protégé in Pamplona, Fermin.

It is one of the oldest constellations, dating back to at least the Early Bronze Age when it marked the location of the Sun during the spring equinox.

Its importance to the agricultural calendar influenced various bull figures in the mythologies of Ancient Sumer, Akkad, Assyria, Babylon, Egypt, Greece, and Rome.

In his book 'Robin Hood: Green Lord of the Wildwood' (2016),John Matthews interprets the scene from the ballad in which Sir Richard-at-Lee awards, for the love of Robin Hood, a prize of a white bull to the winner of a wrestling match as seeming 'to hark back to an ancient time when the presentation of such a valuable, and probably sacred beast, would have represented an offering to the gods'.