Burmese clothing

Burmese clothing also features great diversity in terms of textiles, weaves, fibers, colours and materials, including velvet, silk, lace, muslin, and cotton.

[1] Trade with neighboring societies has been dated to the Pyu era, and certainly enriched the material culture, with imported textiles used for ritual and costume.

[1] For instance, the Mingalazedi Pagoda, built during the reign of Narathihapate, contains enshrined articles of satin and velvet clothing, which were not locally produced.

[2] Vincenzo Sangermano, an Italian priest who was posted in the Konbaung kingdom at the turn of the 19th century, observed that locals were "splendid and extravagant in their dress.

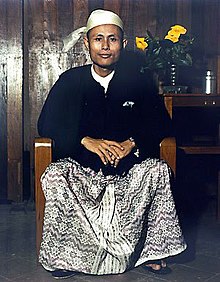

[3] These accessories accompanied traditional attire, consisting of a sarong-like wrap – paso for men or a htamein for women – both of which were made of cotton or silk.

[3] Men and women alike dressed in their finest attire, including ornamented jackets, for visits to pagodas and other important events.

Unlike in neighboring French Indochina, the Burmese monarchy was completely dismantled, creating an immediate vacuum for state sponsorship of material culture, institutions, and traditions.

[9] The colonial era ushered in a wave of non-aristocratic nouveau riche Burmese who sought to adopt the styles and costumes of the aristocrats of pre-colonial times.

[11][10] Inspired by Gandhi's Swadeshi movement, Burmese nationalists also waged campaigns boycotting imported goods, including clothing, to promote the consumption of locally produced garments.

[10] Clothing styles also evolved during the colonial era; the voluminous taungshay paso and htamein with its train, were abandoned in favor of a simpler longyi that was more convenient to wear.

[12] Similarly, women began wearing hairstyles like amauk (အမောက်), consisting of crested bangs curled at the top, with the traditional hair bun (ဆံထုံး).

The pre-colonial htamein features a broad train called yethina (ရေသီနား) and is only seen in modern times as wedding attire or a dance costume.

[17] The name acheik may derive from the name of the quarter in which the weavers lived, Letcheik Row (လက်ချိတ်တန်း); the term itself was previously called waik (ဝိုက်), referring to the woven zig-zag pattern.

[2] The wave-like patterns may have in fact been inspired by Neolithic motifs and natural phenomena (i.e., waves, clouds, indigenous flora and fauna).

[17] For business and formal occasions, Bamar men wear a Manchu jacket called a taikpon eingyi (တိုက်ပုံအင်္ကျီ, [taɪʔpòʊɴ]) over a mandarin collar shirt.

The most formal rendition of Myanmar's national costume for females includes a buttonless tight-fitting hip-length jacket called htaingmathein (ထိုင်မသိမ်း, [tʰàɪɴməθéɪɴ]), sometimes with flared bottoms and embroidered sequins.

The Burmese national costume for men includes a kerchief called gaung baung (ခေါင်းပေါင်း, [ɡáʊɴbáʊɴ]), which is worn for formal functions.

The Chin peoples are a heterogenous collection of ethnic groups that generally live in western Myanmar and speak related Kuki-Chin languages.

[20] Mon women traditionally wear a shawl called yat toot, which is wrapped diagonally over the chest covering one shoulder with one end dropping behind the back.

Archaeological evidence from the Dvaravati era (direct ancestors of the Mon people) portrays ladies wearing what seems to be a similar shawl hanging from their shoulder.