Byblos syllabary

[2] A four-line part of inscription l consisting of characters not elsewhere found in Proto-Byblian texts has been interpreted as an Egyptian dating formula in the hieratic script.

[4] When such an object was later reused, the original text was largely erased and replaced by an inscription in Phoenician alphabetic characters.

Several of these Phoenician inscriptions are dated to the 10th century BCE, which suggests that objects with Pseudo-hieroglyphs may have remained in use longer than is usually assumed.

Colless believes that the proto-alphabet evolved as a simplification of the syllabary, moving from syllabic to consonantal writing, in the style of the Egyptian script (which did not normally indicate vowels).

Thus, in his view, the inscriptions are an important link between the Egyptian hieroglyphic script and the later Semitic abjads derived from Proto-Sinaitic.

The corpus of inscriptions is generally considered far too small to permit a systematic decipherment on the basis of an internal analysis of the texts.

Yet already in 1946, one year after Dunand published the inscriptions, a claim for its decipherment was made, by Edouard Dhorme, a renowned Orientalist and former cryptanalyst from Paris.

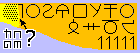

He noted that on the back of one of the inscribed bronze plates was a much shorter inscription ending in a row of seven nearly identical chevron-like marks, very much like our number "1111111".

Dhorme now interpreted the whole word ('b-..-..-t') as Phoenician "b(a) + š(a)-n-t", "in the year (of)" (Hebrew bišnat), which gave him the phonetic meanings of all four signs.

These he substituted in the rest of the inscriptions, thereby looking for recognizable parts of more Phoenician words that would give him the reading of more signs.

In 1961 and 1962 Malachi Martin published two articles, after an autopsy of all inscriptions then in existence (one tablet had been partly lost when Dunand had tried to remove its thick oxide crust[13]).

The first article[14] was devoted to vague, half-erased traces of Proto-Byblian signs on several objects, already hinted at by Dunand.

Martin there saw parallels with Egyptian hieroglyphs, Phoenician consonantal signs, and also two presumed determinatives ("to pray, speak" and "deity, Lord (of)").

Variants he attributed to the different writing materials (stone, metal), or achievement and freedom of individual engravers.

His 27 classes seem to suggest that Martin thought it possible that the syllabary might be an alphabet, but he did not draw this conclusion explicitly.

For example, the sign which in Phoenician has the value g (Hebrew gimel), is assumed to have the phonetic value ga. A sign which resembles an Egyptian hieroglyph meaning "King of Upper Egypt" is interpreted as "mulku" (Semitic for 'regal'; compare Hebrew mèlekh, 'king'), which furnished the phonetic reading mu.

As noted earlier, James Hoch (1990) sees the source of the signs in Egyptian Old Kingdom characters (c. 2700–2200 BC) and so this West Semitic syllabary would have been invented in that period.

In 2008 Jan Best, a Dutch prehistorian and protohistorian, published an article Breaking the Code of the Byblos Script.

He found that the -u/-e ambiguity seen in wa-ka-ya-lu/e, which is also known in Linear A (where the same word is spelled sometimes ending in -u, sometimes in -e), was quite common on tablets c and d.[20] Best concluded that most Byblos syllables belong to four vowel sequences (like la, le, li, lu—an -o series -*lo seems to be absent).

At the end of tablet c the conspicuous number 'seven' corresponds with the names of the seven men who oversaw the building project.

), a petty ruler at Alalakh; and among the seven dedicators on tablet c we encounter a name that sounds familiar: Ya-wa-ne Yu-za-le-yu-su, or 'the Greek Euzaleos'.

[25] Best surmised that the building of the three temples for the Sun god, with rich temple gifts (gold, oil, rituals), may have been meant to propitiate the Egyptian pharaoh and to tempt him to support Yarimlim and Ammitaku against the Hittite king Hattusilis I who threatened to attack the region around 1650 BCE.

The idea that the syllabic Linear A Script from Crete had a number of Semitic characteristics encountered some resistance among those scholars who specialised in Ancient Greek.

[30] Ihor Rassokha, professor of the Department of History and Cultural Studies of the Kharkiv National Academy of Municipal Economy wrote the article "Indo-European origin of alphabetic systems and deciphering of the Byblos script."