Byzantine–Arab wars (780–1180)

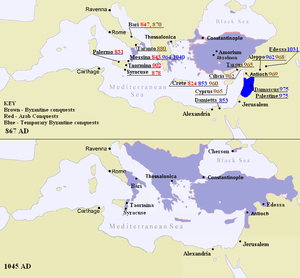

The Levant Egypt North Africa Anatolia & Constantinople Border conflicts Sicily and Southern Italy Naval warfare Byzantine reconquest Between 780–1180, the Byzantine Empire and the Abbasid & Fatimid caliphates in the regions of Iraq, Palestine, Syria, Anatolia and Southern Italy fought a series of wars for supremacy in the Eastern Mediterranean.

After a period of indecisive and slow border warfare, a string of almost unbroken Byzantine victories in the late 10th and early 11th centuries allowed three Byzantine Emperors, namely Nikephoros II Phokas, John I Tzimiskes and finally Basil II to recapture territory lost to the Muslim conquests in the 7th century Arab–Byzantine wars under the failing Heraclian Dynasty.

[4] Nonetheless, the Arabs remained a fierce opponent to the Byzantines and a temporary Fatimid recovery after c. 970 had the potential to reverse many of the earlier victories.

[7] The death of Manuel Komnenos in 1180 ended military campaigns far from Constantinople and after the Fourth Crusade both the Byzantines and the Arabs were engaged in other conflicts until they were conquered by the Ottoman Turks in the 15th and 16th centuries, respectively.

Forced to deal with the rebel Thomas the Slav, Michael had few troops to spare against a small Arab invasion of 40 ships and 10,000 men against Crete, which fell in 824.

Al-Mu'tasim however gained the upper hand with his 838 victories at Dazimon, Ancyra and finally at Amorium[13]—the sack of the latter is presumed to have caused great grief for Theophilos and was one of the factors of his death in 842.

After Leo's death in 912 the Empire became embroiled in problems with the regency of the seven-year-old Constantine VII and with invasions of Thrace by Simeon I of Bulgaria.

[20] The situation changed however when the admiral Romanos Lekapenos assumed power as a co-emperor with three of his rather useless sons and Constantine VII, thus ending the internal problems with the government.

Bardas Phokas the Elder had originally supported the claims of Constantine VII against those of Romanos I, and his position as strategos of the Armeniakon Theme made him the ideal candidate for war against the Caliphate.

[25] Instead, Nikephoros had to march rapidly to the East where Saif al-Daula of the Hamdanid dynasty, the Emir of Aleppo, had taken 30,000 men into Imperial territory,[25] attempting to take advantage of the army's absence in Crete.

Instead, Saif found himself fleeing from battle with 300 cavalry and his army torn to pieces by a brilliantly planned ambush in the mountain passes of Asia Minor.

[26] When Nikephoros arrived and linked up with his brother, their army operated efficiently and had by early 962 returned some 55 walled tows in Cilicia to Byzantium.

Like many regencies, that of Basil II proved chaotic and not without scheming of ambitious generals, such as Nikephoros, or internal fighting between Macedonian levies, Anatolians, and even the pious crowd of the Hagia Sophia.

Byzantine success was not total; in 964 another failed attempt was made to take Sicily by sending an army led by an illegitimate nephew of Nikephoros, Manuel Phokas.

[5] Having defeated their Islamic opponents, the Fatimids saw no reason to stop at Antioch and Aleppo, cities in the hands of the Christian Byzantines, making their conquest more important.

[5] After dealing with more Church matters, Tzimiskes returned in the spring of 975; Syria, Lebanon, and much of Palestine fell to the imperial armies of Byzantium.

[30] As an imperial vassal the Emir pleaded to the Byzantines for military assistance, since the city was under siege by Abu Mansoor Nizar al-Aziz Billah.

In 998, the Byzantines under the successor of Bourtzes, Damian Dalassenos, launched an attack on Apamea, but the Fatimid general Jaush ibn al-Samsama defeated them in battle on 19 July 998.

Basil spent three months in Syria, during which the Byzantines raided as far as Baalbek, took and garrisoned Shaizar, and captured three minor forts in its vicinity (Abu Qubais, Masyath, and 'Arqah), and sacked Rafaniya.

[35] The military force of the Arab world had been in decline since the 9th century, illustrated by losses in Mesopotamia and Syria, and by the slow conquest of Sicily.

While the Byzantines attained successes against the Arabs, a slow internal decay after 1025 a.d. was not arrested, precipitating a general decline of the Empire during the 11th century.

Very frequent revolt and civil war between the bureaucrats and the military aristocracy for supremacy; which as a result facilitated unruly mercenaries and foreign raiders like the Turks or Pechenegs to plunder the interior with little meaningful resistance).

Initial Byzantine success led to the fall of Messina in 1038, followed by Syracuse in 1040, but the expedition was riddled with internal strife and was diverted to a disastrous course against the Normans in southern Italy.

Facing hardship to enter the Armenian Highlands, he ignored the truce made with the Seljuks and marched to retake recently lost fortresses around Manzikert.

Byzantine attention was focused primarily on the Normans and the Crusades during this period, and they would not fight the Arabs again until the end of the reign of John II Comnenus.

[43] The new Byzantine Emperor, Manuel I Komnenos, enjoyed the idea of conquering Egypt, whose vast resources in grain and in native Christian manpower (from the Copts) would be no small reward, even if shared with the Crusaders.

[46] In 1177, a fleet of 150 ships was sent by Manuel I to invade Egypt, but it returned home after appearing off Acre due to the refusal of Philip, Count of Flanders, and many important nobles of the Kingdom of Jerusalem to help.

[47] In that year Manuel Komnenos suffered a defeat in the Battle of Myriokephalon against Kilij Arslan II of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rûm.

[48] Even so, the Byzantine Emperor continued to have an interest in Syria, planning to march his army south in a pilgrimage and show of strength against Saladin's might.

Nonetheless, like many of Manuel's goals, this proved unrealistic, and he had to spend his final years working hard to restore the Eastern front against Iconium, which had deteriorated in the time wasted in fruitless Arab campaigns.