History of the Byzantine Empire

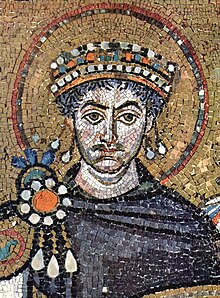

During the reign of Justinian I (r. 527–565), the Empire reached its greatest extent after reconquering much of the historically Roman western Mediterranean coast, including north Africa, Italy, and Rome itself, which it held for two more centuries.

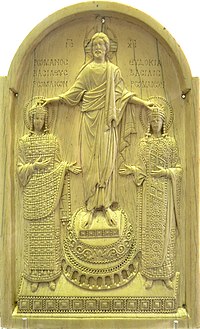

[5] During the Macedonian dynasty (9th–11th centuries), the Empire again expanded and experienced a two-century long renaissance, which came to an end with the loss of much of Asia Minor to the Seljuk Turks after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071.

It struggled to recover during the 12th century, but was delivered a mortal blow during the Fourth Crusade, when Constantinople was sacked and the Empire dissolved and divided into competing Byzantine Greek and Latin realms.

[10] In 330, he founded Constantinople as a second Rome on the site of Byzantium, which was well-positioned astride the trade routes between East and West; it was a superb base from which to guard the Danube river, and was reasonably close to the Eastern frontiers.

[19] The Eastern Empire was largely spared the difficulties faced by the West in the third and fourth centuries, due in part to a more firmly established urban culture and greater financial resources, which allowed it to placate invaders with tribute and pay foreign mercenaries.

Thus, by suggesting that Theodoric conquer Italy as his Ostrogothic kingdom, Zeno maintained at least a nominal supremacy in that western land while ridding the Eastern Empire of an unruly subordinate.

[33] In 551, a noble of Visigothic Hispania, Athanagild, sought Justinian's help in a rebellion against the king, and the emperor dispatched a force under Liberius, who, although elderly, proved himself a successful military commander.

In the Pandects, completed under Tribonian's direction in 533, order and system were found in the contradictory rulings of the great Roman jurists, and a textbook, the Institutiones, was issued to facilitate instruction in the law schools.

Their reigns were marked both by major external threats, from the west and the east, which reduced the territory of the empire to a fraction of its 6th-century extent, and by significant internal turmoil and cultural transformation.

[50] The void left by the disappearance of the old semi-autonomous civic institutions was filled by the theme system, which entailed the division of Asia Minor into "provinces" occupied by distinct armies which assumed civil authority and answered directly to the imperial administration.

[51] The withdrawal of massive numbers of troops from the Balkans to combat the Persians and then the Arabs in the east opened the door for the gradual southward expansion of Slavic peoples into the peninsula, and, as in Anatolia, many cities shrank to small fortified settlements.

In the next year Constantine IV signed a treaty with the Bulgar khan Asparukh, and the new Bulgarian state assumed sovereignty over a number of Slavic tribes which had previously, at least in name, recognized Byzantine rule.

[53] In 687–688, the emperor Justinian II led an expedition against the Slavs and Bulgars which made significant gains, although the fact that he had to fight his way from Thrace to Macedonia demonstrates the degree to which Byzantine power in the north Balkans had declined.

The territorial losses were accompanied by a cultural shift; urban civilization was massively disrupted, classical literary genres were abandoned in favor of theological treatises,[60] and a new "radically abstract" style emerged in the visual arts.

The Byzantine historian Theophylact Simocatta, writing during the reign of Heraclius (r. 610–641), relayed information about China's geography, its capital city Khubdan (Old Turkic: Khumdan, i.e. Chang'an), its current ruler Taisson whose name meant "Son of God" (Chinese: Tianzi, although this could be derived from the name of Emperor Taizong of Tang), and correctly pointed to its reunification by the Sui dynasty (581–618) as occurring during the reign of Maurice, noting that China had previously been divided politically along the Yangzi River by two warring nations.

[68][73] Leo III the Isaurian (717–741 AD) turned back the Muslim assault in 718, and achieved victory with the major help of the Bulgarian khan Tervel, who killed 32,000 Arabs with his army in 740 in Akroinon.

[76] Leo's order to remove the golden Christ over the Chalke Gates and to have it replaced with a simple cross was motivated by the need to mollify the rising tide of popular objection to all religious icons.

The Byzantine Empire reached its height under the Macedonian emperors (of Greek descent) of the late 9th, 10th, and early 11th centuries, when it gained control over the Adriatic Sea, southern Italy, and all of the territory of tsar Samuel of Bulgaria.

[101] A great imperial expedition under Leo Phocas and Romanos I Lekapenos ended with another crushing Byzantine defeat at the Battle of Achelous in 917, and the following year the Bulgarians were free to ravage northern Greece.

[116] During this period, the Byzantine Empire employed a strong civil service staffed by competent aristocrats that oversaw the collection of taxes, domestic administration, and foreign policy.

From the outset of his reign, Alexios faced a formidable attack by the Normans under Robert Guiscard and his son Bohemund of Taranto, who captured Dyrrhachium and Corfu, and laid siege to Larissa in Thessaly.

In the course of his twenty-five year reign, John made alliances with the Holy Roman Empire in the west, decisively defeated the Pechenegs at the Battle of Beroia,[138] and personally led numerous campaigns against the Turks in Asia Minor.

According to George Ostrogorsky, Andronikos was determined to root out corruption: Under his rule the sale of offices ceased; selection was based on merit, rather than favoritism; officials were paid an adequate salary so as to reduce the temptation of bribery.

[160] Despite his military background, Andronikos failed to deal with Isaac Komnenos, Béla III who reincorporated Croatian territories into Hungary, and Stephen Nemanja of Serbia who declared his independence from Byzantium.

[167] The crusaders accepted the suggestion that in lieu of payment they assist the Venetians in the capture of the (Christian) port of Zara in Dalmatia (vassal city of Venice, which had rebelled and placed itself under Hungary's protection in 1186).

[179] Massive construction projects were completed in Constantinople to repair the damages of the Fourth Crusade, but none of these initiatives was of any comfort to the farmers in Asia Minor, suffering raids from fanatical ghazis.

The Serbian king Stefan Uroš IV Dušan made significant territorial gains in Byzantine Macedonia in 1345 and conquered large swaths of Thessaly and Epirus in 1348.

By the time of the fall of Constantinople, the only remaining territory of the Byzantine Empire was the Despotate of the Morea, which was ruled by brothers of the last Emperor and continued on as a tributary state to the Ottomans.

Incompetent rule, failure to pay the annual tribute and a revolt against the Ottomans finally led to Mehmed II's invasion of Morea in May 1460; he conquered the entire Despotate by the summer.

All Balkan countries (Greeks, Bulgarians, Serbs, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Bosniaks, Kosovars, Albanians, Croats, Slovenians and Turks) were influenced by the Vlachs from the early medieval times.