Roman art

The development of realistic technique is credited to Zeuxis and Parrhasius, who according to ancient Greek legend, are said to have once competed in a bravura display of their talents, history's earliest descriptions of trompe-l'œil painting.

[9] Partly because Roman cities were mostly far larger than the Greek city-states in population, and generally less provincial, art in Ancient Rome took on a wider, and sometimes more utilitarian, purpose.

The Church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople employed nearly 10,000 workmen and artisans, in a final burst of Roman art under Emperor Justinian (527–565 CE), who also ordered the creation of the famous mosaics of Basilica of San Vitale in the city of Ravenna.

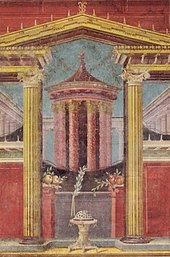

A succession of dated styles have been defined and analysed by modern art historians beginning with August Mau, showing increasing elaboration.

During the Hellenistic period, it evoked the pleasures of the countryside and represented scenes of shepherds, herds, rustic temples, rural mountainous landscapes and country houses.

It is possible to see evidence of Greek knowledge of landscape portrayal in Plato's Critias (107b–108b): ... and if we look at the portraiture of divine and of human bodies as executed by painters, in respect of the ease or difficulty with which they succeed in imitating their subjects in the opinion of onlookers, we shall notice in the first place that as regards the earth and mountains and rivers and woods and the whole of heaven, with the things that exist and move therein, we are content if a man is able to represent them with even a small degree of likeness ...[16]Roman still life subjects are often placed in illusionist niches or shelves and depict a variety of everyday objects including fruit, live and dead animals, seafood, and shells.

There are a very few large designs, including a very fine group of portraits from the 3rd century with added paint, but the great majority of the around 500 survivals are roundels that are the cut-off bottoms of wine cups or glasses used to mark and decorate graves in the Catacombs of Rome by pressing them into the mortar.

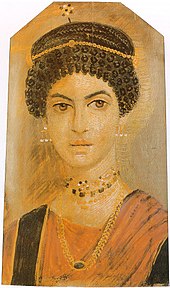

[26] One of the most famous Alexandrian-style portrait medallions, with an inscription in Egyptian Greek, was later mounted in an Early Medieval crux gemmata in Brescia, in the mistaken belief that it showed the pious empress and Gothic queen Galla Placida and her children;[27] in fact the knot in the central figure's dress may mark a devotee of Isis.

Josephus describes the painting executed on the occasion of Vespasian and Titus's sack of Jerusalem: There was also wrought gold and ivory fastened about them all; and many resemblances of the war, and those in several ways, and variety of contrivances, affording a most lively portraiture of itself.

[34]These paintings have disappeared, but they likely influenced the composition of the historical reliefs carved on military sarcophagi, the Arch of Titus, and Trajan's Column.

In the second zone, to the left, is a city encircled with crenellated walls, in front of which is a large warrior equipped with an oval buckler and a feathered helmet; near him is a man in a short tunic, armed with a spear...Around these two are smaller soldiers in short tunics, armed with spears...In the lower zone a battle is taking place, where a warrior with oval buckler and a feathered helmet is shown larger than the others, whose weapons allow to assume that these are probably Samnites.This episode is difficult to pinpoint.

An Etruscan speciality was near life size tomb effigies in terracotta, usually lying on top of a sarcophagus lid propped up on one elbow in the pose of a diner in that period.

The Romans did not generally attempt to compete with free-standing Greek works of heroic exploits from history or mythology, but from early on produced historical works in relief, culminating in the great Roman triumphal columns with continuous narrative reliefs winding around them, of which those commemorating Trajan (113 AD) and Marcus Aurelius (by 193) survive in Rome, where the Ara Pacis ("Altar of Peace", 13 BC) represents the official Greco-Roman style at its most classical and refined, and the Sperlonga sculptures it at its most baroque.

[42] For a much wider section of the population, moulded relief decoration of pottery vessels and small figurines were produced in great quantity and often considerable quality.

Even the most important imperial monuments now showed stumpy, large-eyed figures in a harsh frontal style, in simple compositions emphasizing power at the expense of grace.

Ernst Kitzinger found in both monuments the same "stubby proportions, angular movements, an ordering of parts through symmetry and repetition and a rendering of features and drapery folds through incisions rather than modelling...

[49] Contrary to the belief of early archaeologists, many of these sculptures were large polychrome terra-cotta images, such as the Apollo of Veii (Villa Givlia, Rome), but the painted surface of many of them has worn away with time.

This unprecedented achievement, over 650 foot of spiraling length, presents not just realistically rendered individuals (over 2,500 of them), but landscapes, animals, ships, and other elements in a continuous visual history – in effect an ancient precursor of a documentary movie.

[50] During the Christian era after 300 AD, the decoration of door panels and sarcophagi continued but full-sized sculpture died out and did not appear to be an important element in early churches.

[52] Producers of the millions of small oil lamps sold seem to have relied on attractive decoration to beat competitors and every subject of Roman art except landscape and portraiture is found on them in miniature.

Metalwork was highly developed, and clearly an essential part of the homes of the rich, who dined off silver, while often drinking from glass, and had elaborate cast fittings on their furniture, jewellery, and small figurines.

A number of important hoards found in the last 200 years, mostly from the more violent edges of the late empire, have given us a much clearer idea of Roman silver plate.

In the Empire medallions in precious metals began to be produced in small editions as imperial gifts, which are similar to coins, though larger and usually finer in execution.

Though concrete had been invented a thousand years earlier in the Near East, the Romans extended its use from fortifications to their most impressive buildings and monuments, capitalizing on the material's strength and low cost.

[58] The concrete core was covered with a plaster, brick, stone, or marble veneer, and decorative polychrome and gold-gilded sculpture was often added to produce a dazzling effect of power and wealth.

[59] During the Republican era, Roman architecture combined Greek and Etruscan elements, and produced innovations such as the round temple and the curved arch.

[60] As Roman power grew in the early empire, the first emperors inaugurated wholesale leveling of slums to build grand palaces on the Palatine Hill and nearby areas, which required advances in engineering methods and large scale design.

It held over 50,000 spectators, had retractable fabric coverings for shade, and could stage massive spectacles including huge gladiatorial contests and mock naval battles.

The Pantheon (dedicated to all the planetary gods) is the best preserved temple of ancient times with an intact ceiling featuring an open "eye" in the center.

Their standing masonry remains are especially impressive, such as the Pont du Gard (featuring three tiers of arches) and the aqueduct of Segovia, serving as mute testimony to their quality of their design and construction.