Byzantine mosaics

[3] Although Byzantine mosaics evolved out of earlier Hellenistic and Roman practices and styles,[4] craftspeople within the Byzantine Empire made important technical advances[4] and developed mosaic art into a unique and powerful form of personal and religious expression that exerted significant influence on Islamic art produced in Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates and the Ottoman Empire.

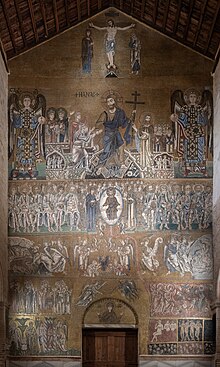

Byzantine mosaics went on to influence artists in the Norman Kingdom of Sicily, in the Republic of Venice, and, carried by the spread of Orthodox Christianity, in Bulgaria, Serbia, Romania and Russia.

In another great Constantinian basilica, the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, the original mosaic floor with typical Roman geometric motifs is partially preserved.

Orthodox bishops under Justinian continued and expanded the construction of basilicas to the adjacent port city of Classe, commissioning some of the finest mosaics anywhere in the world.

[13] In addition, archeological discoveries in the 19th and 20th centuries unearthed many Early Byzantine mosaics in the Middle East, including the Madaba Map in Jordan as well as other examples in Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Israel, and Palestine.

For instance, the monasteries at Hosios Loukas, Daphni, and Nea Moni of Chios have all been recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites,[16] and they contain some of the most magnificent Byzantine mosaics from this period.

[2] Until the disastrous sack of Constantinople in 1204 at the hands of the Fourth Crusader Army, Byzantium was seen by many in Europe as the last light of civilization due to its inherited legacy of Rome and continued cultural sophistication.

For instance, the Norman King Roger II of Sicily was actively hostile to Byzantium, but he imported Greek craftspeople to create the mosaics for Cefalù Cathedral.

[5] Similarly, the earliest surviving mosaics in St. Mark's Basilica in Venice were probably created by artists who had left Constantinople in the mid-11th century and also worked at Torcello Cathedral.

[18] During the Byzantine period, craftsmen expanded the materials that could be turned into tesserae, beginning to include gold leaf and precious stones, and perfected their construction.

In fact, mosaic art was commonly used to decorate the floors and walls of public and private spaces with geometric patterns and secular figurative subjects.

For example, the deeply influential painter and historian Giorgio Vasari defined the Renaissance as a rejection of "that clumsy Greek style" ("quella greca goffa maniera").

By the 1040s, Byzantine mosaic artists were working in the Hagia Sophia at Kiev, leaving a lasting legacy not only on Russian decorative arts but also medieval painting.