Islamic art

[3] From its beginnings, Islamic art has been based on the written version of the Quran and other seminal religious works, which is reflected by the important role of calligraphy, representing the word as the medium of divine revelation.

Nevertheless, representations of human and animal forms historically flourished in nearly all Islamic cultures, although, partly because of opposing religious sentiments, living beings in paintings were often stylized, giving rise to a variety of decorative figural designs.

[21] The disappearance of royal-sponsored figurative arts in Arabic-speaking lands at a later period is best explained by the overthrow of their ruling dynasties and reduction of most their territories to Ottoman provincial dependencies, not by religious prohibition.

[25] An ivory casket carved in early eleventh century Cordova shows a Spanish Muslim ruler holding a cup seated upon a lion throne, similar to that of Solomon.

[30] Chinese influences included the early adoption of the vertical format natural to a book, which led to the development of a birds-eye view where a very carefully depicted background of hilly landscape or palace buildings rises up to leave only a small area of sky.

The spiritual centre of this movement is the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB), with leading teachers such as A.D. Pirous, Ahmad Sadali, Mochtar Apin and Umi Dachlan as their main representatives.

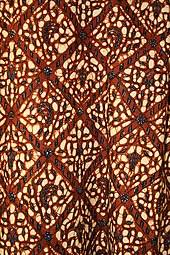

Their versatility is utilized in everyday Islamic and Muslim life, from floor coverings to architectural enrichment, from cushions to bolsters to bags and sacks of all shapes and sizes, and to religious objects (such as a prayer rug, which would provide a clean place to pray).

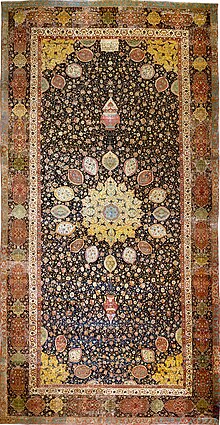

There are a few survivals of the grand Egyptian 16th century carpets, including one almost as good as new discovered in the attic of the Pitti Palace in Florence, whose complex patterns of octagon roundels and stars, in just a few colours, shimmer before the viewer.

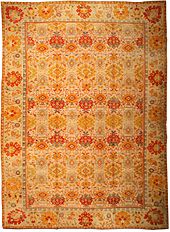

Spanish carpets, which sometimes interrupted typical Islamic patterns to include coats of arms, enjoyed high prestige in Europe, being commissioned by royalty and for the Papal Palace, Avignon, and the industry continued after the Reconquista.

Apart from the products of city workshops, in touch with trading networks that might carry the carpets to markets far away, there was also a large and widespread village and nomadic industry producing work that stayed closer to traditional local designs.

Ottoman İznik pottery produced most of the best work in the 16th century, in tiles and large vessels boldly decorated with floral motifs influenced, once again, by Chinese Yuan and Ming ceramics.

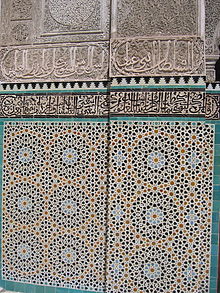

The geometric patterns, such as modern North African zellij work, made of small tiles each of a single colour but different and regular shapes, are often referred to as "mosaic", which is not strictly correct.

The Mughals made much less use of tiling, preferring (and being able to afford) "parchin kari", a type of pietra dura decoration from inlaid panels of semi-precious stones, with jewels in some cases.

Medieval Islamic metalwork offers a complete contrast to its European equivalent, which is dominated by modelled figures and brightly coloured decoration in enamel, some pieces entirely in precious metals.

More common objects with elaborate decoration include massive low candlesticks and lamp-stands, lantern lights, bowls, dishes, basins, buckets (these probably for the bath),[57] and ewers, as well as caskets, pen-cases and plaques.

Traditional Islamic furniture, except for chests, tended to be covered with cushions, with cupboards rather than cabinets for storage, but there are some pieces, including a low round (strictly twelve-sided) table of about 1560 from the Ottoman court, with marquetry inlays in light wood, and a single huge ceramic tile or plaque on the tabletop.

Some designs are calligraphic, especially when made for palls to cover a tomb, but more are surprisingly conservative versions of the earlier traditions, with many large figures of animals, especially majestic symbols of power like the lion and eagle.

[66] The Shroud of St Josse is a famous samite cloth from East Persia, which originally had a carpet-like design with two pairs of confronted elephants, surrounded by borders including rows of camels and an inscription in Kufic script, from which the date appears to be before 961.

A 16th-century circular ceiling for a tent, 97 cm across, shows a continuous and crowded hunting scene; it was apparently looted by the army of Suleiman the Magnificent in his invasion of Persia in 1543–45, before being taken by a Polish general at the Siege of Vienna in 1683.

By combining the various traditions that they had inherited, and by readapting motifs and architectural elements, artists created little by little a typically Muslim art, particularly discernible in the aesthetic of the arabesque, which appears both on monuments and in illuminated Qurans.

A series of military victories by Christian monarchs had reduced Islamic Spain by the end of the 14th century to the city of Granada, ruled by the Nasrid dynasty, who managed to maintain their hold until 1492.

[79] Innovations in ceramics from this period include the production of minai ware and the manufacture of vessels, not out of clay, but out of a silicon paste ("fritware"), while metalworkers began to encrust bronze with precious metals.

During the 15th century this dynasty gave rise to a golden age in Persian manuscript painting, including renowned painters such as Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād, but also a multitude of workshops and patrons.

The Seljuq Turks pushed beyond Iran into Anatolia, winning a victory over the Byzantine Empire in the Battle of Manzikert (1071), and setting up a sultanate independent of the Iranian branch of the dynasty.

Influence from Byzantine visual vocabulary (blue and gold coloring, angelic and victorious motifs, symbology of drapery) combined with Mongoloid facial types in 12th-century book frontispieces.

The Mughal court had access to European prints and other art, and these had increasing influence, shown in the gradual introduction of aspects of Western graphical perspective, and a wider range of poses in the human figure.

The arts of jewelry and hardstone carving of gemstones, such as jasper, jade, adorned with rubies, diamonds and emeralds are mentioned by the Mughal chronicler Abu'l Fazl, and a range of examples survive; the series of hard stone daggers in the form of horses' heads is particularly impressive.

The Iranian Safavids, a dynasty stretching from 1501 to 1786, is distinguished from the Mughal and Ottoman Empires, and earlier Persian rulers, in part through the Shi'a faith of its shahs, which they succeeded in making the majority denomination in Persia.

Architecture flourished, attaining a high point with the building program of Shah Abbas in Isfahan, which included numerous gardens, palaces (such as Ali Qapu), an immense bazaar, and a large imperial mosque.

The albums were the creations of connoisseurs who bound together single sheets containing paintings, drawings, or calligraphy by various artists, sometimes excised from earlier books, and other times created as independent works.