C. V. Raman

[13] At age 18, while still a graduate student, he published his first scientific paper on "Unsymmetrical diffraction bands due to a rectangular aperture" in the British journal Philosophical Magazine in 1906.

[13] Aware of Raman's capacity, his physics teacher Rhishard Llewellyn Jones insisted he continue research in England.

[23] Raman followed suit and qualified for the Indian Finance Service achieving first position in the entrance examination in February 1907.

With their support, he obtained permission to conduct research at IACS in his own time even "at very unusual hours," as Raman later reminisced.

[26] The work inspired IACS to publish a journal, Bulletin of Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, in 1909 in which Raman was the major contributor.

Sudhangsu Kumar Banerji (who later become Director General of Observatories of India Meteorological Department), a PhD scholar under Ganesh Prasad, was his first student.

But to his advantage, the terms and conditions as a professor were explicitly indicated in the report of his joining the university, which stated:Mr C.V. Raman's acceptance of the Sir T N Palit Professorship on condition that he will not be required to go out of India... Reported that Mr C. V. Raman joined his appointment as Palit Professor of Physics from 2.7.17... Mr Raman informed that he will not be required to take any teaching work in MA and MSc classes, to the detriment of his own research or assisting advanced students in their researches.

[38] Maharaja Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV, the King of Mysore, Jamsetji Tata and Nawab Sir Mir Osman Ali Khan, the Nizam of Hyderabad, had contributed the lands and funds for the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore.

The Viceroy of India, Lord Minto approved the establishment in 1909, and the British government appointed its first director, Morris Travers.

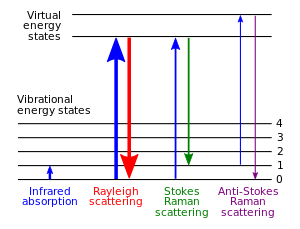

As a necessary preliminary to the discussion, a theoretical calculation and experimental observations of the intensity of molecular scattering in water will be presented.

There Compton presented his experimental findings, which William Duane of Harvard University argued with his own with evidence that light was a wave.

[34][78] Referring to the invention, Raman later remarked, "When I got my Nobel Prize, I had spent hardly 200 rupees on my equipment,"[79] although it was obvious that his total expenditure for the entire experiment was much more than that.

[80] From that moment they could employ the instrument using monochromatic light from a mercury arc lamp which penetrated transparent material and was allowed to fall on a spectrograph to record its spectrum.

[86] Raman presented the formal and detailed description as "A new radiation" at the meeting of the South Indian Science Association in Bangalore on 16 March.

[92] He made a series of experimental verification, after which he commented, saying, "It appears to me that this very beautiful discovery which resulted from Raman's long and patient study of the phenomenon of light scattering is one of the most convincing proofs of the quantum theory".

[100][91] With another student, Nagendra Nath, he provided the correct theoretical explanation for the acousto-optic effect (light scattering by sound waves) in a series of articles resulting in the celebrated Raman–Nath theory.

[23] The wedding day is popularly recorded as on 6 May,[122][123][124] but Raman's great-niece and biographer, Uma Parameswaran,[125] revealed a factual date of 2 June 1907.

[130]) His wife later jokingly recounted that their marriage was not so much about her musical prowess (she was playing veena when they first met) as "the extra allowance which the Finance Department gave to its married officers.

Raman's elder brother Chandrasekhara Subrahmanya Ayyar's son Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar won the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physics.

[131] Throughout his life, Raman developed an extensive personal collection of stones, minerals, and materials with interesting light-scattering properties, which he obtained from his world travels and as gifts.

He nominated Raman for the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1930, presented him the Hughes Medal as President of the Royal Society in 1930, and recommended him for the position of Director at IISc in 1932.

[145] Traditional pagri (Indian turban) with a tuft underneath and a upanayana (Hindu sacred thread) were his signature attire.

"[159] From October 1933 to March 1934, Max Born was employed by IISc as Reader in Theoretical Physics following the invitation by Raman early in 1933.

[167] Born was nominated several times for the Nobel Prize specifically for his contributions to lattice theory, and eventually won it for his statistical works on quantum mechanics in 1954.

But Raman clearly foresaw as he replied to C. Subramaniam, then the Minister for Finance Education in Madras, that his proposal to Nehru's government "would be met with a refusal."

As to problems of food resources in India, his advice to the government was, "We must stop breeding like pigs and the matter will solve itself.

"[136] The Indian Academy of Sciences was born out of conflicts during the procedures of the proposal for a national scientific organization in line with the Royal Society.

[160] He lacked diplomatic personality with other colleagues, which S. Ramaseshan, his nephew and later Director of IISc, reminisced, saying, "Raman went in there like a bull in a china shop.

[24] Aston even made a personal attack on Born by referring to him as someone "who was rejected by his own country, a renegade and therefore a second-rate scientist unfit to be part of the faculty, much less to be the head of the department of physics.

The committee, chaired by James Irvine, Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of St Andrews, reported in March that Raman had misused the funds and entirely shifted the "centre of gravity" towards research in physics, and also that the proposal of Born as Professor of Mathematical Physics (which was already approved by the Council in November 1935) was not financially feasible.