Caenorhabditis elegans

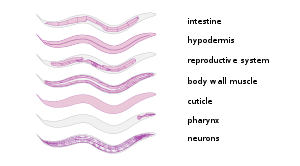

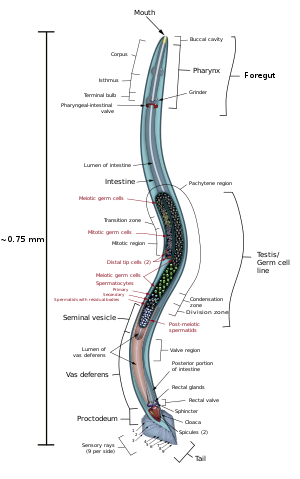

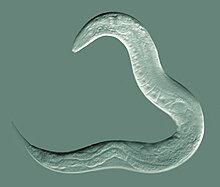

It has a cuticle (a strong outer covering, as an exoskeleton), four main epidermal cords, and a fluid-filled pseudocoelom (body cavity).

A set of ridges on the lateral sides of the body cuticle, the alae, is believed to give the animal added traction during these bending motions.

In relation to lipid metabolism, C. elegans does not have any specialized adipose tissues, a pancreas, a liver, or even blood to deliver nutrients compared to mammals.

[23] C. elegans has excitatory cholinergic and inhibitory GABAergic motor neurons which connect with body wall muscles to regulate movement.

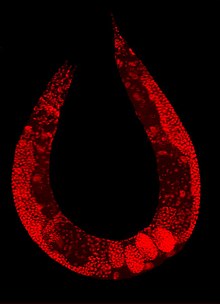

[24] Numerous gut granules are present in the intestine of C. elegans, the functions of which are still not fully known, as are many other aspects of this nematode, despite the many years that it has been studied.

They are very similar to lysosomes in that they feature an acidic interior and the capacity for endocytosis, but they are considerably larger, reinforcing the view of their being storage organelles.

This death fluorescence typically takes place in an anterior to posterior wave that moves along the intestine, and is seen in both young and old worms, whether subjected to lethal injury or peacefully dying of old age.

Recent chemical analysis has identified the blue fluorescent material they contain as a glycosylated form of anthranilic acid (AA).

The worms that reproduce through self-fertilization are at risk for high linkage disequilibrium, which leads to lower genetic diversity in populations and an increase in accumulation of deleterious alleles.

[33] The tra-1 is a gene within the TRA-1 transcription factor sex determination pathway that is regulated post-transcriptionally and works by promoting female development.

[33] In hermaphrodites (XX), there are high levels of tra-1 activity, which produces the female reproductive system and inhibits male development.

[30] The closely related organism Caenorhabditis briggsae has been studied extensively and its whole genome sequence has helped put together the missing pieces in the evolution of C. elegans sex determination.

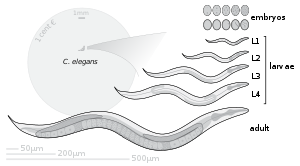

[54] Important developmental events controlled by heterochronic genes include the division and eventual syncitial fusion of the hypodermic seam cells, and their subsequent secretion of the alae in young adults.

They possess chemosensory receptors which enable the detection of bacteria and bacterial-secreted metabolites (such as iron siderophores), so that they can migrate towards their bacterial prey.

[63] C. elegans can also use different species of yeast, including Cryptococcus laurentii and C. kuetzingii, as sole sources of food.

[67] Pathogenic bacteria can also form biofilms, whose sticky exopolymer matrix could impede C. elegans motility [68] and cloaks bacterial quorum sensing chemoattractants from predator detection.

[70] Nematodes can survive desiccation, and in C. elegans, the mechanism for this capability has been demonstrated to be late embryogenesis abundant proteins.

[79] Research has explored the neural and molecular mechanisms that control several behaviors of C. elegans, including chemotaxis, thermotaxis, mechanotransduction, learning, memory, and mating behaviour.

[84] The use of OP50 does not demand any major laboratory safety measures, since it is non-pathogenic and easily grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) media overnight.

[92] This ability has been mapped down to a single gene, sid-2, which, when inserted as a transgene in other species, allows them to take up RNA for RNAi as C. elegans does.

[96] Furthermore, during meiosis in C. elegans the tumor suppressor BRCA1/BRC-1 and the structural maintenance of chromosomes SMC5/SMC6 protein complex interact to promote high fidelity repair of DNA double-strand breaks.

[100] As for most model organisms, scientists that work in the field curate a dedicated online database and WormBase is that for C. elegans.

[105] Knockdown of the nucleotide excision repair gene Xpa-1 increased sensitivity to UV and reduced the life span of the long-lived mutants.

Consistent with the idea that oxidative DNA damage causes aging, it was found that in C. elegans, exosome-mediated delivery of superoxide dismutase (SOD) reduces the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and significantly extends lifespan, i.e. delays aging under normal, as well as hostile conditions.

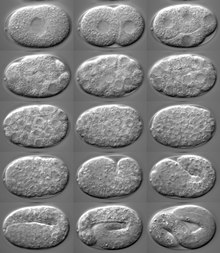

[110] Moreover, extensive research on C. elegans has identified RNA-binding proteins as essential factors during germline and early embryonic development.

[122] C. elegans has also been demonstrated to sleep after exposure to physical stress, including heat shock, UV radiation, and bacterial toxins.

[137] C. elegans and other nematodes are among the few eukaryotes currently known to have operons; these include trypanosomes, flatworms (notably the trematode Schistosoma mansoni), and a primitive chordate tunicate Oikopleura dioica.

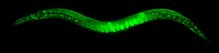

Several scientists have won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for scientific discoveries made working with C. elegans.

It was awarded in 2002 to Sydney Brenner, H. Robert Horvitz, and John Sulston for their work on the genetics of organ development and programmed cell death, in 2006 to Andrew Fire and Craig C. Mello for their discovery of RNA interference, and in 2024 to Victor Ambros and Gary Ruvkun for their discovery of microRNA and its role in gene regulation.

[152][153] In 2008, Martin Chalfie shared a Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on green fluorescent protein; some of the research involved the use of C. elegans.