Arabidopsis thaliana

A winter annual with a relatively short lifecycle, A. thaliana is a popular model organism in plant biology and genetics.

[15] The plant was first described in 1577 in the Harz Mountains by Johannes Thal [de] (1542–1583), a physician from Nordhausen, Thüringen, Germany, who called it Pilosella siliquosa.

[16] A. thaliana is native to Europe, Asia, and Africa, and its geographic distribution is rather continuous from the Mediterranean to Scandinavia and Spain to Greece.

[23] Like most Brassicaceae species, A. thaliana is edible by humans in a salad or cooked, but it does not enjoy widespread use as a spring vegetable.

The first mutant in A. thaliana was documented in 1873 by Alexander Braun, describing a double flower phenotype (the mutated gene was likely Agamous, cloned and characterized in 1990).

Laibach continued his important contributions to A. thaliana research by collecting a large number of accessions (often questionably referred to as "ecotypes").

In the 1950s and 1960s, John Langridge and George Rédei played an important role in establishing A. thaliana as a useful organism for biological laboratory experiments.

[50] Other background lines less-often cited in the scientific literature are Ws, or Wassilewskija, C24, Cvi, or Cape Verde Islands, Nossen, etc.

[53] Columbia (named for the location of Rédei's former institution, University of Missouri-Columbia) was the reference accession sequenced in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative.

[54][55] In 2005, scientists at Purdue University proposed that A. thaliana possessed an alternative to previously known mechanisms of DNA repair, producing an unusual pattern of inheritance, but the phenomenon observed (reversion of mutant copies of the HOTHEAD gene to a wild-type state) was later suggested to be an artifact because the mutants show increased outcrossing due to organ fusion.

Also, as an individual plant can produce several thousand seeds, each of the above criteria leads to A. thaliana being valued as a genetic model organism.

Kaiser et al.[60] showed that in A. thaliana cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) induced by UV light can be repaired by expression of CPD photolyase.

Leaf primordia are initiated by the suppression of the genes and proteins of class I KNOX family (such as SHOOT APICAL MERISTEMLESS).

[66] By wet-mounting seedlings in water or in culture media, plants may be imaged uninvasively, obviating the need for fixation and sectioning and allowing time-lapse measurements.

A. thaliana was used extensively in the study of the genetic basis of phototropism, chloroplast alignment, and stomal aperture and other blue light-influenced processes.

[72] When the onset of darkness is unusually early, A. thaliana reduces its metabolism of starch by an amount that effectively requires division.

In 1990, Janet Braam and Ronald W. Davis determined that A. thaliana exhibits thigmomorphogenesis in response to wind, rain and touch.

[76] In 2002, Massimo Pigliucci found that A. thaliana developed different patterns of branching in response to sustained exposure to wind, a display of phenotypic plasticity.

[80] Potter et al., 2018 finds synthesis is induced by a combination of at least 2 facts, cell-specific transcription factors (TFs) and the accessibility of the chromatin.

Many model systems have been developed to better understand interactions between plants and bacterial, fungal, oomycete, viral, and nematode pathogens.

An example where A. thaliana was used to determine the genes responsible for nonhost resistance is Blumeria graminis, the causal agent of powdery mildew of grasses.

[citation needed] Both flagellin and UV-C act similarly to increase homologous recombination in A. thaliana, as demonstrated by Molinier et al. 2006.

The initiation of the SAR pathway was first demonstrated in A. thaliana in which increased SA levels are recognized by nonexpresser of PR genes 1 (NPR1)[94] due to redox change in the cytosol, resulting in the reduction of NPR1.

[97] This has led to the belief that plant-pathogen resistance is an evolutionary mechanism that has built up over generations to respond to dynamic environments, such as increased predation and extreme temperatures.

[97] In the future, comparisons of the pathosystems of wild populations + their coevolved pathogens with wild-wild hybrids of known parentage may reveal new mechanisms of balancing selection.

In life history theory we may find that A. thaliana maintains certain alleles due to pleitropy between plant-pathogen effects and other traits, as in livestock.

Xiao et al. 2005 have shown that the powdery mildew immunity mediated by A. thaliana's RPW8 (which has a CCHELO domain) is dependent on two members of this family: EDS1 itself and PAD4.

[109] An analysis of the genome-wide pattern of linkage disequilibrium suggested that self-pollination evolved roughly a million years ago or more.

However, these meioses can provide the adaptive benefit of recombinational repair of DNA damages during formation of germ cells at each generation.

A physical mechanism for self-pollination in A. thaliana is through pre-anthesis autogamy, such that fertilisation takes place largely before flower opening.

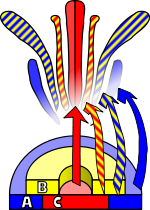

A schematic of PAMP-triggered immunity: recognition of flagellin by FLS2 (top left); effector-triggered immunity depicted through the recognition of avrRpt2 by RPS2 through RIN4 (top-right); microscopic view of callose deposition in an A. thaliana leaf (bottom left); an example of no hypersensitive response (HR) above, and HR in A. thaliana leaves below (bottom right)

on the roots of Arabidopsis thaliana

a) Overview of an A. thaliana root (primary root) with numerous root hairs, b) Biofilm-forming bacteria, c) Fungal or oomycete hyphae surrounding the root surface, d) Primary root densely covered by spores and protists, e, f) Protists, most likely belonging to the Bacillariophyceae class, g) Bacteria and bacterial filaments, h, i) Different bacterial individuals showing great varieties of shapes and morphological features [ 81 ]