Circular dichroism

[3] This phenomenon was discovered by Jean-Baptiste Biot, Augustin Fresnel, and Aimé Cotton in the first half of the 19th century.

[2] Vibrational circular dichroism, which uses light from the infrared energy region, is used for structural studies of small organic molecules, and most recently proteins and DNA.

At a single point in space, the circularly polarized-vector will trace out a circle over one period of the wave frequency, hence the name.

For left circularly polarized light (LCP) with propagation towards the observer, the electric vector rotates counterclockwise.

In a CD experiment, equal amounts of left and right circularly polarized light of a selected wavelength are alternately radiated into a (chiral) sample.

One of the two polarizations is absorbed more than the other one, and this wavelength-dependent difference of absorption is measured, yielding the CD spectrum of the sample.

Due to the interaction with the molecule, the electric field vector of the light traces out an elliptical path after passing through the sample.

In ordered structures lacking two-fold rotational symmetry, optical activity,[8][9] including differential transmission[10] (and reflection[11]) of circularly polarized waves also depends on the propagation direction through the material.

To calculate molar ellipticity, the sample concentration (g/L), cell pathlength (cm), and the molecular weight (g/mol) must be known.

In general, the phenomenon of circular dichroism will be exhibited in absorption bands of any optically active molecule.

The capacity of CD to give a representative structural signature makes it a powerful tool in modern biochemistry with applications that can be found in virtually every field of study.

CD is the higher resolution technique since it is only observed at wavelengths where the chiral molecule absorbs light.

ORD is particularly useful for unsubstituted sugars as this class of biomolecule does not possess chromophores that absorb in the UV-Vis regions accessible via commercial CD instruments.

It can, for instance, be used to study how the secondary structure of a molecule changes as a function of temperature or of the concentration of denaturing agents, e.g. Guanidinium chloride or urea.

In this way it can reveal important thermodynamic information about the molecule (such as the enthalpy and Gibbs free energy of denaturation) that cannot otherwise be easily obtained.

The signals obtained in the 250–300 nm region are due to the absorption, dipole orientation and the nature of the surrounding environment of the phenylalanine, tyrosine, cysteine (or S-S disulfide bridges) and tryptophan amino acids.

Rather, near-UV CD spectra provide structural information on the nature of the prosthetic groups in proteins, e.g., the heme groups in hemoglobin and cytochrome c. Visible CD spectroscopy is a very powerful technique to study metal–protein interactions and can resolve individual d–d electronic transitions as separate bands.

Optical activity in transition metal ion complexes have been attributed to configurational, conformational and the vicinal effects.

Klewpatinond and Viles (2007) have produced a set of empirical rules for predicting the appearance of visible CD spectra for Cu2+ and Ni2+ square-planar complexes involving histidine and main-chain coordination.

However, CD spectroscopy is a quick method that does not require large amounts of proteins or extensive data processing.

Thus CD can be used to survey a large number of solvent conditions, varying temperature, pH, salinity, and the presence of various cofactors.

CD spectroscopy has also been done using semiconducting materials such as TiO2 to obtain large signals in the UV range of wavelengths, where the electronic transitions for biomolecules often occur.

Measurement of CD is also complicated by the fact that typical aqueous buffer systems often absorb in the range where structural features exhibit differential absorption of circularly polarized light.

Phosphate, sulfate, carbonate, and acetate buffers are generally incompatible with CD unless made extremely dilute e.g. in the 10–50 mM range.

Most common organic solvents such as acetonitrile, THF, chloroform, dichloromethane are however, incompatible with far-UV CD.

In practice these spectra are measured not in vacuum but in an oxygen-free instrument (filled with pure nitrogen gas).

Once oxygen has been eliminated, perhaps the second most important technical factor in working below 200 nm is to design the rest of the optical system to have low losses in this region.

Critical in this regard is the use of aluminized mirrors whose coatings have been optimized for low loss in this region of the spectrum.

Light from synchrotron sources has a much higher flux at short wavelengths, and has been used to record CD down to 160 nm.

[19] At the quantum mechanical level, the feature density of circular dichroism and optical rotation are identical.

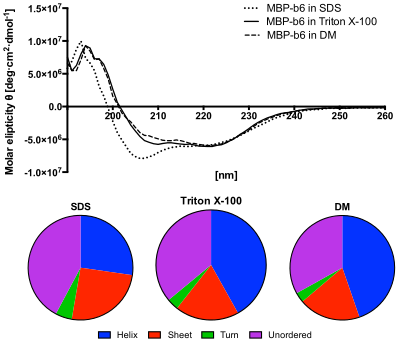

Lower panel: The content of secondary structures predicted from the CD spectra using the CDSSTR algorithm. The protein in SDS solution shows increased content of unordered structures and decreased helices content. [ 12 ]