Bookbinding

[2] Writers in the Hellenistic-Roman culture wrote longer texts as scrolls; these were stored in boxes or shelving with small cubbyholes, similar to a modern wine rack.

The modern English word "book" comes from the Proto-Germanic *bokiz, referring to the beechwood on which early written works were recorded.

[3] The book was not needed in ancient times, as many early Greek texts—scrolls—were 30 pages long, which were customarily folded accordion-fashion to fit into the hand.

Torah scrolls, editions of first five books of the Old Testament, known as the Israelite (or Hebrew) Bible, were—and still are—also held in special holders when read.

Two ancient polyptychs, a pentaptych and octoptych, excavated at Herculaneum employed a unique connecting system that presages later sewing on thongs or cords.

[4] At the turn of the first century, a kind of folded parchment notebook called pugillares membranei in Latin, became commonly used for writing throughout the Roman Empire.

The idea spread quickly through the early churches, and the word "Bible" comes from the town where the Byzantine monks established their first scriptorium, Byblos, in modern Lebanon.

The codex-style book, using sheets of either papyrus or vellum (before the spread of Chinese papermaking outside of Imperial China), was invented in the Roman Empire during the 1st century AD.

[8] First described by the poet Martial from Roman Spain, it largely replaced earlier writing mediums such as wax tablets and scrolls by the year 300 AD.

Since early books were exclusively handwritten on handmade materials, sizes and styles varied considerably, and there was no standard of uniformity.

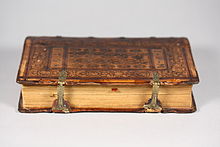

[12] The earliest surviving European bookbinding is the St Cuthbert Gospel of about 700, in red goatskin, now in the British Library, whose decoration includes raised patterns and coloured tooled designs.

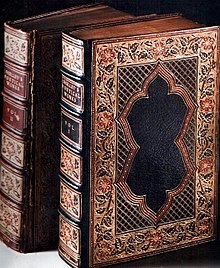

Very grand manuscripts for liturgical rather than library use had covers in metalwork called treasure bindings, often studded with gems and incorporating ivory relief panels or enamel elements.

[13] Luxury medieval books for the library had leather covers decorated, often all over, with tooling (incised lines or patterns), blind stamps, and often small metal pieces of furniture.

Medieval stamps showed animals and figures as well as the vegetal and geometric designs that would later dominate book cover decoration.

[15] Bookbinding in medieval China replaced traditional Chinese writing supports such as bamboo and wooden slips, as well as silk and paper scrolls.

[17] The initial phase of this evolution, the accordion-folded palm-leaf-style book, most likely came from India and was introduced to China via Buddhist missionaries and scriptures.

[17] With the arrival (from the East) of rag paper manufacturing in Europe in the late Middle Ages and the use of the printing press beginning in the mid-15th century, bookbinding began to standardize somewhat, but page sizes still varied considerably.

Paper leaves also meant that heavy wooden boards and metal furniture were no longer necessary to keep books closed, allowing for much lighter pasteboard covers.

[20] Leipzig, a prominent centre of the German book-trade, in 1739 had 20 bookshops, 15 printing establishments, 22 book-binders and three type-foundries in a population of 28,000 people.

[21] In the German book-distribution system of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the end-user buyers of books "generally made separate arrangements with either the publisher or a bookbinder to have printed sheets bound according to their wishes and their budget".

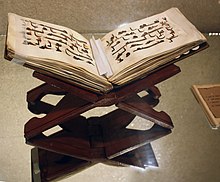

[22] The reduced cost of books facilitated cheap lightweight Bibles, made from tissue-thin oxford paper, with floppy covers, that resembled the early Arabic Qurans, enabling missionaries to take portable books with them around the world, and modern wood glues enabled the addition of paperback covers to simple glue bindings.

The history of book-binding methods features:[23] For several hundred years, Bernard Middleton reminds us, most newly published books were sold with customised or temporary bindings.

[29] Until the mid-20th century, covers of mass-produced books were laid with bookcloth, but from that period onward, most publishers adopted clothette, a kind of textured paper which vaguely resembles cloth but is easily differentiated on close inspection.

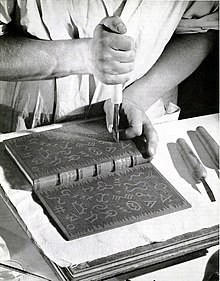

Bookbinders can learn the craft through apprenticeship; by attending specialized trade schools;[33] by taking classes in the course of university studies, or by a combination of those methods.

"In a typical design binding, the binder selects an already printed book, disassembles it, and rebinds it in a style of fine binding—rounded and backed spine, laced-in boards, sewn headbands, decorative end sheets, leather cover etc.

Many times, books that need to be restored are hundreds of years old, and the handling of the pages and binding has to be undertaken with great care and a delicate hand.

The preparation of the "foundations" of the book could mean the difference between a beautiful work of art and a useless stack of paper and leather.

This practice is reflected in the industry standards ANSI/NISO Z39.41[44] and ISO 6357,[45] but "lack of agreement in the matter persisted among English-speaking countries as late as the middle of the twentieth century, when books bound in Britain still tended to have their titles read up the spine".

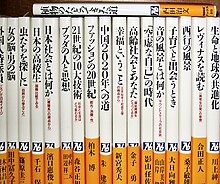

[46] In most of continental Europe, Latin America, and French Canada the spine text, when the book is standing upright, runs from the bottom up, so the title can be read by tilting the head to the left.

This allows the reader to read spines of books shelved in alphabetical order in accordance to the usual way: left-to-right and top-to-bottom.

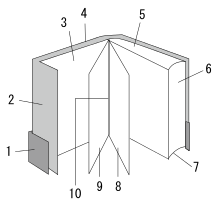

- Belly band

- Flap

- Endpaper

- Book cover

- Head

- Fore edge

- Tail

- Right page, recto

- Left page, verso

- Gutter

(left) ascending

(middle) descending

(right) upright