Caliban over Setebos

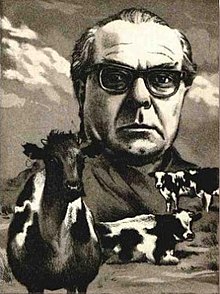

[1] Here it is the poet Georg Düsterhenn, who, like Schmidt, comes from Hamburg-Hamm, has Lower Silesian-lausitz roots, is an atheist and spent Second World War as a typing pool soldier in Norway.

There he wants to meet his childhood crush Fiete Methe again, in order to "decisively & irresistibly make himself schmaltzy" for a volume of poetry that will be an economic failure and thus reduce his taxable income.

[12] The text is preceded by a motto, which parodies in phonetic English an epigram dedicated to Herodotus from the Anthologia Graeca, whose historical work is divided into nine books named after the muses.

Schmidt consistently ignores the rules of orthography: Not only is the respective dialect of the characters imitated, but the chosen spelling exhausts the sound and meaning possibilities of a word.

With 3,000 fioriturs & pralltrillers, which required considerable art & effort.The deliberate polysemy of his language has its origins in Schmidt's etymology theory, which was fed by his encounter with psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud.

[17] As the literary scholar Friedhelm Rathjen notes, Caliban over Setebos seems disintegrated: It is not immediately clear to the reader what sense the various elements of the plot make.

[21] An evil God who does not care about the suffering of his creatures was already a theme in his 1949 story Leviathan and in the title Nobodaddy's Kinder, under which his short novel Brand's Haide, Aus dem Leben eines Fauns and Schwarze Spiegel were published as a trilogy in 1963.

[26] In the sign for the bus stop, Düsterhenn's "green-pale 'H' of the face" catches the eye, the fare is an obolus - this coin was given to the dead to pay the ferryman Charon for his crossing of the Styx, the Kötelbeck, a small stream at the entrance to the village, has a "stügisch" effect and "'Der Erste Schiffer'" himself makes an appearance in the form of a man urinating by the wayside.

The relationship between the two is changed by Schmidt, however, because in Caliban über Setebos it is not the man who leads the woman, but vice versa (namely up a narrow staircase to Düsterhenn's room in the inn), and it is not he who looks around at her, but she at him.

[31] H. Levy, who chauffeurs Düsterhenn on his escape from the village, is portrayed as a Jew; Bernd Rauschenbach recognizes in him a portrait of Schmidt's Jewish brother-in-law Rudy Kiesler, who fled to the US with his wife from the National Socialists in 1933.

Rainer Maria Rilke's solemn Sonnets to Orpheus, written in 1922, are quoted and comically reinterpreted above all in faecal language or obscene passages, for example in the description of the sex act between Rieke-Fiete and the house servant: sonnets 2/IV (the "unicorn"), 2/VII ("between the streaming poles of feeling fingers") and 1/XVII ("See, the machine, how it rolls and avenges itself and disfigures and weakens us" - in Schmidt: "him disfigured & weakened") are quoted there.

[33] Stefan Jurczyk also recognizes references in the story to the ancient myths of Pentheus and Actaion, who were torn apart by maenads and dogs respectively after watching scenes that were forbidden to the male eye.

[34] Schmidt adopted the poetological principle of basing a narrative set in the present on an ancient myth, which is contrasted and satirized by the sometimes profane or burlesque content, from his role model James Joyce.

Joyce himself is mentioned twice by name in Caliban over Setebos - once for his alleged ability to reconstruct a family's history from their dirty laundry, then Düsterhenn imagines an encounter with the man who died in 1941, paraphrasing the thought of his own death.

In Caliban über Setebos, reverence is paid to him, among other things, with a reminiscence of a reader of Friedrich Rückert's supposedly erotic poem Der Ehebrecher:[37] In reality, the poem is called The Cup of Honor and contains no sexual content whatsoever - a classic Freudian blunder; on the other hand, the story teems with allusions to Freud's 1908 essay Character and Analeroticism, which Schmidt had read shortly before writing it.

[41] Werner Schwarze discovers in Caliban über Setebos not only allusions to classical ancient mythology, but also to that of the Egyptians: Thus, the goddess of death Hathor can be recognized as well as Isis, who already played a role in the story Kundian Harness, also contained in the volume Cows in Semi-Mourning, or the creator god Ptah.

[43] Karl May, on whose texts Schmidt had tested his etymological theory (Sitara und der Weg dorthin, published in 1963, the year Caliban über Setebos was written), receives a covert citation when Düsterhenn's kitschy, amateurish poetry is presented in the Urania chapter.

[47] Friedhelm Rathjen recognizes several allusions in Caliban over Setebos to the novel The Night Life of the Gods by the American popular writer Thorne Smith.

Schmidt had moved from this federal state to the more liberal Hesse in 1955 after his short novel Seelandschaft mit Pocahontas had earned him criminal proceedings for blasphemy and distribution of lewd writings.

Because EHRHARDT didn't get his turn anyway; let's not kid ourselves.The question of what Brentano, highlighted in small capitals, might love is an allusion to the rumors about the CDU politician's homosexuality - in keeping with the themes of the story, in which not only female homosexuality plays a role, but also in the relationship between Düsterhenn and H. Levy ("Hauptsache er'ss nich direkt schwul"[52]) latently masculine as well, for example when Düsterhenn jumps into the open back of Levy's car at the end.

[53] Robert Wohlleben assumes that Schmidt wrote Caliban über Setebos as a model for his readers in order to make clear how his multireferential etymological texts should be read.

In KAFF auch Mare Crisium from 1960, he had worked with text foils for the first time in a Joycian manner, namely with the Nibelungensage and the myth of El Cid: "The non-participation of the readership exceeded the boldest expectations".

By so obviously basing his Düsterhenn story on the Orpheus myth, Schmidt wanted to educate his readers to read in multiple dimensions - as a preliminary exercise to Zettel's dream.

This polysemantic procedure collides with Schmidt's depth psychological etymological theory, which attempts to reduce everything to a single meaning, namely the sex drive.

[57] On January 19, 1964, Schmidt explained in a letter to his editor Ernst Krawehl why he no longer wanted to emphasize the mythological parts of the story typographically, as originally planned: "Fucking myth!

[58] In the figure of the impotent, trivial and money-hungry (psychoanalytically interpreted: anal fixation) Düsterhenn, the writer Schmidt and his attitude to his bread work are reflected in sharp self-criticism.

[59] Marius Fränzel places the underlying Orpheus myth at the center of his interpretation: according to him, the story is about a "monomaniacal loner" on a "journey into the past", but he himself is not clear about its deeper motivation: Düsterhenn is a deluded man.

The impotence that has become apparent allows Düsterhenn a distanced, observant attitude towards sexuality in the sense of the etymological theory (this is the meaning of voyeurism in the Terpsichore chapter); he is no longer at the mercy of his urges: At the end of the plot, he describes himself as "ä sädder änd a veiser Männ"[61] (this is a quote from Samuel Coleridge's ballad The Rime of the Ancient Mariner).

At the same time, Düsterhenn also freed himself from poetry - he lost his rhyming lexicon during his escape - so that in future he could depict in prose what had previously been repressed, describe the world realistically and without kitsch as what he was convinced it was: a "Uni= sive Perversum", senseless "Fusch=Werk".