The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

The Wedding-Guest's reaction turns from amusement to impatience to fear to fascination as the mariner's story progresses, as can be seen in the language style; Coleridge uses narrative techniques such as personification and repetition to create a sense of danger, the supernatural, or serenity, depending on the mood in different parts of the poem.

[2] The poem begins with an old grey-bearded sailor, the Mariner, stopping a guest at a wedding ceremony to tell him a story of a sailing voyage he took long ago.

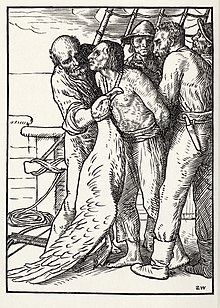

In anger, the crew forces the mariner to wear the dead albatross about his neck, perhaps to illustrate the burden he must suffer from killing it, or perhaps as a sign of regret: Ah!

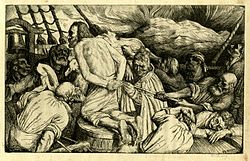

With a roll of the dice, Death wins the lives of the crew members and Life-in-Death the life of the mariner, a prize she considers more valuable.

In a trance, the mariner hears two spirits discussing his voyage and penance, and learns that the ship is being powered supernaturally: The air is cut away before, And closes from behind.

[3] After finishing his story, the mariner leaves, and the wedding-guest returns home, waking the next morning "a sadder and a wiser man".

The poem received mixed reviews from critics, and Coleridge was once told by the publisher that most of the book's sales were to sailors who thought it was a naval songbook.

On this second voyage Cook crossed three times into the Antarctic Circle to determine whether the fabled great southern continent Terra Australis existed.

[6] The discussion had turned to a book that Wordsworth was reading,[7] that described a privateering voyage in 1719 during which a melancholy sailor, Simon Hatley, shot a black albatross.

Bernard Martin argues in The Ancient Mariner and the Authentic Narrative that Coleridge was also influenced by the life of Anglican clergyman John Newton, who had a near-death experience aboard a slave ship.

[9][10] It is argued that the harbour at Watchet in Somerset was the primary inspiration for the poem, although some time before, John Cruikshank, a local acquaintance of Coleridge's, had related a dream about a skeleton ship crewed by spectral sailors.

In the one, incidents and agents were to be, in part at least, supernatural, and the excellence aimed at was to consist in the interesting of the affections by the dramatic truth of such emotions, as would naturally accompany such situations, supposing them real.

In this idea originated the plan of the Lyrical Ballads; in which it was agreed, that my endeavours should be directed to persons and characters supernatural, or at least Romantic; yet so as to transfer from our inward nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith.

[13]In Table Talk, Coleridge wrote: Mrs. Barbauld once told me that she admired The Ancient Mariner very much, but that there were two faults in it – it was improbable, and had no moral.

It ought to have had no more moral than the Arabian Nights' tale of the merchant's sitting down to eat dates by the side of a well, and throwing the shells aside, and lo!

[14]Wordsworth wrote to Joseph Cottle in 1799: From what I can gather it seems that the Ancient Mariner has upon the whole been an injury to the volume, I mean that the old words and the strangeness of it have deterred readers from going on.

If the volume should come to a second Edition I would put in its place some little things which would be more likely to suit the common taste.However, when Lyrical Ballads was reprinted, Wordsworth included it despite Coleridge's objections, writing: The Poem of my Friend has indeed great defects; first, that the principal person has no distinct character, either in his profession of Mariner, or as a human being who having been long under the control of supernatural impressions might be supposed himself to partake of something supernatural; secondly, that he does not act, but is continually acted upon; thirdly, that the events having no necessary connection do not produce each other; and lastly, that the imagery is somewhat too laboriously accumulated.

Yet the Poem contains many delicate touches of passion, and indeed the passion is every where true to nature, a great number of the stanzas present beautiful images, and are expressed with unusual felicity of language; and the versification, though the metre is itself unfit for long poems, is harmonious and artfully varied, exhibiting the utmost powers of that metre, and every variety of which it is capable.

[15] Charles Lamb, who had deeply admired the original for its attention to "Human Feeling", claimed that the gloss distanced the audience from the narrative, weakening the poem's effects.

"Like the Iliad or Paradise Lost or any great historical product, the Rime is a work of trans-historical rather than so-called universal significance.

[19] Coleridge often made changes to his poems and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner was no exception – he produced at least eighteen different versions over the years.

[20](pp 128–129, 134) The 1817 edition, the one most used today and the first to be published under Coleridge's own name rather than anonymously, added a new Latin epigraph but the major change was the addition of the gloss that has a considerable effect on the way the poem reads.

[22] Over all, Coleridge's revisions resulted in the poem losing thirty-nine lines and an introductory prose "Argument", and gaining fifty-eight glosses and a Latin epigraph.

"Ah! well a-day! what evil looks

Had I from old and young!

Instead of the cross, the Albatross

About my neck was hung." [ 3 ] : lines 139–142