California mission clash of cultures

The Spanish occupation of California brought some negative consequences to the Native American cultures and populations, both those the missionaries were in contact with and others that were traditional trading partners.

Each Indian was expected to contribute a certain number of hours' labor each week towards making adobes or roof tiles, working on construction crews, performing some type of handicraft, or farming.

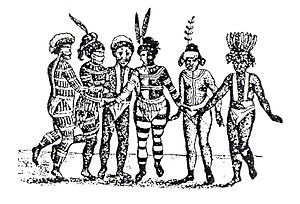

Social organization in precontact California is scarcely recorded, but a ruling elite presided over commoners and an underclass, determined by lineage and cultural inheritance.

Conversely, mission power structure was determined by elections, eliminating traditional Native American social hierarchy and replacing it with a system heavily monitored and often controlled by Franciscans.

[5] The replies, which varied greatly in length, spirit, and even value of information, were collected and prefaced by the Father-Presidente with a short general statement or abstract.

The Indians also spent much of their days learning the Christian faith, and attended worship services several times a day (Fray Gerónimo Boscana, a Franciscan scholar who was stationed at Mission San Juan Capistrano for more than a decade beginning in 1812, compiled what is widely considered to be the most comprehensive study of prehistoric religious practices in the San Juan Capistrano valley).

In addition, Native American cultural and spiritual beliefs about marriage, love, and sex were routinely disrespected or punished.

[9] Once an Indian agreed to become part of the mission community, he or she was forbidden to leave it without a padre's permission, and from then on led a fairly regimented life learning "civilized" ways from the Spaniards.

[12] The canonization of Junípero Serra continues to spark contemporary debate regarding the treatment of Native Americans at the hands of Franciscan missionaries.