Ohlone

[7] The Ohlone living today belong to various geographically distinct groups, most of which are still in their original home territory, though not all; none are currently federally recognized tribes.

British ethnologist Robert Gordon Latham originally used the term "Costanoan" to refer to the linguistically similar but ethnically diverse Native American tribes in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Based on the former, American anthropologist Clinton Hart Merriam referred to the Costanoan groups as "Olhonean" in the early 20th century in his posthumously published field notes,[9] and eventually, the term "Ohlone" has been adopted by most ethnographers, historians, and writers of popular literature.

Cultural arts included basket-weaving skills, seasonal ceremonial dancing events, female tattoos, ear and nose piercings, and other ornamentation.

"A rough husbandry of the land was practiced, mainly by annually setting of fires to burn-off the old growth in order to get a better yield of seeds—or so the Ohlone told early explorers in San Mateo County.

Birds included plentiful ducks, geese, quail, great horned owls, red-shafted flickers, downy woodpeckers, goldfinches, and yellow-billed magpies.

The Chochenyo traditional narratives refer to ducks as food, and Juan Crespí observed in his journal that geese were stuffed and dried "to use as decoys in hunting others".

[19] Researchers are sensitive to limitations in historical knowledge, and careful not to place the spiritual and religious beliefs of all Ohlone people into a single unified worldview.

[22] Kuksu was shared with other indigenous ethnic groups of Central California, such as their neighbors the Miwok and Esselen, also Maidu, Pomo, and northernmost Yokuts.

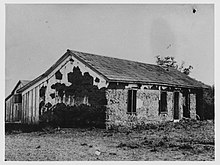

[26] Today, there is a place located in Hollister called Indian Canyon, where a traditional sweat lodge, or Tupentak, has been built for the same ceremonial purposes.

Indian Canyon is also home to many Ohlone people, specifically of the Mutsun band, and serves as an educational, cultural, and spiritual environment for all visitors.

Additionally, through knowing sacred narratives and sharing them with the public through live performances or storytelling, the Ohlone people are able to create an awareness that their cultural group is not extinct, but actually surviving and wanting recognition.

[29] Ohlone folklore and legend centered around the Californian culture heroes of the Coyote trickster spirit, as well as Eagle and Hummingbird (and in the Chochenyo region, a falcon-like being named Kaknu).

Stanger in La Peninsula: "Careful study of artifacts found in central California mounds has resulted in the discovery of three distinguishable epochs or cultural 'horizons' in their history.

The Rumsien were the first Ohlone people to be encountered and documented in Spanish records when, in 1602, explorer Sebastián Vizcaíno reached and named the area that is now Monterey in December of that year.

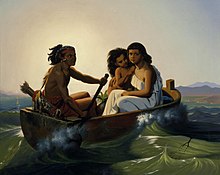

This time, the military expedition was accompanied by Franciscan missionaries, whose purpose was to establish a chain of missions to bring Christianity to the native people.

Natives today are engaging in extensive cultural research to bring back knowledge, narratives, beliefs, and practices of the post-contact days with the Spanish.

[55] Key to their success is in their involvement in unearthing and analyzing their ancestral remains in ancient burial sites, which allows them to "recapture their history and to reconstruct the present and future of their people".

[57] In other grave site, the skeletal remains of two more wolves were found with "braided, uncured yucca or soap root fiber cordage around their necks".

[57] There were many other fragments of remains of animals like deer, squirrel, mountain lion, grizzly bear, fox, badger, blue goose, and elk found as well.

[57] Although the truth may not be known about exactly what these findings mean, the Muwekma and the archeological team analyzed the ritual burial of the animal remains as a way to learn what they may tell about the Ohlone cosmology and cultural system before pre-contact influence.

[59] The tax has no legal ramifications and no connection with the United States government or Internal Revenue Service, but the organization prefers this term (as opposed to merely calling contributions donations) as it asserts indigenous sovereignty.

Ohlone might have originally derived from a Spanish rancho called Oljon, and referred to a single band who inhabited the Pacific Coast near Pescadero Creek.

However, because of its tribal origin, Ohlone is not universally accepted by the native people, and some members prefer to either to continue to use the name Costanoan or to revitalize and be known as the Muwekma.

[67] In 1925, Alfred Kroeber, then director of the Hearst Museum of Anthropology, declared the tribe extinct, which directly led to its losing federal recognition and land rights.

Per Cook, the "Northern Mission Area" means "the region inhabited by the Costanoans and Salinans between San Francisco Bay and the headwaters of the Salinas River.

It was however known to be more densely populated than the southern Salinan territory, per Cook: "The Costanoan density was nearly 1.8 persons per square mile with the maximum in the Bay region.

We can estimate that Cook meant about 18,200 Ohlone based on his own statements (70% of "Northern Mission Area"), plus or minus a few thousand margin for error, but he does not give an exact number.

[85] Eight dialects or languages of Ohlone have been recorded: Awaswas, Chalon, Chochenyo (aka Chocheño), Karkin, Mutsun, Ramaytush, Rumsen, and Tamyen.

[86] There was noticeable competition and some disagreement between the first scholars: Both Merriam and Harrington produced much in-depth Ohlone research in the shadow of the highly published Kroeber and competed in print with him.