Cambrian

[6] The assembly of Gondwana during the Ediacaran and early Cambrian led to the development of new convergent plate boundaries and continental-margin arc magmatism along its margins that helped drive up global temperatures.

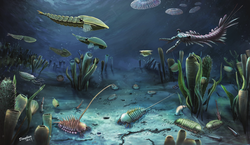

[8] The Cambrian marked a profound change in life on Earth; prior to the Period, the majority of living organisms were small, unicellular and poorly preserved.

The clear fossil record of the Silurian, however, allowed Murchison to correlate rocks of a similar age across Europe and Russia, and on these he published extensively.

The recognition of small shelly fossils before the first trilobites, and Ediacara biota substantially earlier, has led to calls for a more precisely defined base to the Cambrian Period.

After decades of careful consideration, a continuous sedimentary sequence at Fortune Head, Newfoundland was settled upon as a formal base of the Cambrian Period, which was to be correlated worldwide by the earliest appearance of Treptichnus pedum.

[20] Discovery of this fossil a few metres below the GSSP led to the refinement of this statement, and it is the T. pedum ichnofossil assemblage that is now formally used to correlate the base of the Cambrian.

[1] The ash horizon in Oman from which this date was recovered corresponds to a marked fall in the abundance of carbon-13 that correlates to equivalent excursions elsewhere in the world, and to the disappearance of distinctive Ediacaran fossils (Namacalathus, Cloudina).

[20] *Most Russian paleontologists define the lower boundary of the Cambrian at the base of the Tommotian Stage, characterized by diversification and global distribution of organisms with mineral skeletons and the appearance of the first Archaeocyath bioherms.

There was a rapid diversification of metazoans during this epoch, but their restricted geographic distribution, particularly of the trilobites and archaeocyaths, have made global correlations difficult, hence ongoing efforts to establish a GSSP.

Secondary markers for the base of the Miaolingian include the appearance of many acritarchs forms, a global marine transgression, and the disappearance of the polymerid trilobites, Bathynotus or Ovatoryctocara.

[33] Those not in favour of the existence of Pannotia show the Iapetus opening during the Late Neoproterozoic, with up to c. 6,500 km (c. 4038 miles) between Laurentia and West Gondwana at the beginning of the Cambrian.

These covered an area of > 2.1 × 106 km2 across northern, central and Western Australia regions of Gondwana making it one of the largest, as well as the earliest, LIPs of the Phanerozoic.

[35] However, some models show these terranes as part of a single independent microcontinent, Greater Avalonia, lying to the west of Baltica and aligned with its eastern (Timanide) margin, with the Iapetus to the north and the Ran Ocean to the south.

[6] During the Cambrian, the terranes that would form Kazakhstania later in the Paleozoic were a series of island arc and accretionary complexes that lay along an intra-oceanic convergent plate margin to the south of North China.

[6] Its northern margin was passive for much of the Paleozoic, with thick sequences of platform carbonates and fluvial to marine sediments resting unconformably on Precambrian basement.

Also, early in the Cambrian, the eastern margin of South China changed from passive to active, with the development of oceanic volcanic island arcs that now form part of the Japanese terrane.

This bioturbation decreased the burial rates of organic carbon and sulphur, which over time reduced atmospheric and oceanic oxygen levels, leading to widespread anoxic conditions.

[47] Periods of higher rates of continental weathering led to increased delivery of nutrients to the oceans, boosting productivity of phytoplankton and stimulating metazoan evolution.

[46][47][48] Overall, these dynamic, fluctuating environments, with global and regional anoxic incursions resulting in extinction events, and periods of increased oceanic oxygenation stimulating biodiversity, drove evolutionary innovation.

[8][48][7] The basal Cambrian δ13C excursion (BACE), together with low δ238U and raised δ34S indicates a period of widespread shallow marine anoxia, which occurs at the same time as the extinction off the Ediacaran acritarchs.

However, during the early Cambrian, a series of linked δ13C and δ34S excursions indicate high burial rates of both organic carbon and pyrite in biologically productive yet anoxic ocean floor waters.

The oxygen-rich waters produced by these processes spread from the deep ocean into shallow marine environments, extending the habitable regions of the seafloor.

Increased temperatures led to a global sea level rise that flooded continental shelves and interiors with anoxic waters from the deeper ocean and drowned carbonate platforms of archaeocyathan reefs, resulting in the widespread accumulation of black organic-rich shales.

[49][17] The base of the Miaolingian is marked by the Redlichiid–Olenellid extinction carbon isotope event (ROECE), which coincides with the main phase of Kalkarindji volcanism.

[7] During the Miaolingian, orogenic events along the Australian-Antarctic margin of Gondwana led to an increase in weathering and an influx of nutrients into the ocean, raising the level of productivity and organic carbon burial.

[7] This indicates similar geochemical conditions to Stages 2 and 3 of the early Cambrian existed, with the expansion of seafloor anoxia enhancing the burial rates of organic matter and pyrite.

[52] These variations and slow decrease in Mg2+/Ca2+ of seawater were due to low oxygen levels, high continental weathering rates and the geochemistry of the Cambrian seas.

[55][56] Although molecular clock estimates suggest terrestrial plants may have first emerged during the Middle or Late Cambrian, the consequent large-scale removal of the greenhouse gas CO2 from the atmosphere through sequestration did not begin until the Ordovician.

What made them so apparently abundant was their heavy armor reinforced by calcium carbonate (CaCO3), which fossilized far more easily than the fragile chitinous exoskeletons of other arthropods, leaving numerous preserved remains.

The Ediacaran biota suffered a mass extinction at the start of the Cambrian Period, which corresponded with an increase in the abundance and complexity of burrowing behaviour.