Camera obscura

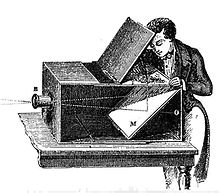

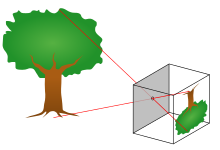

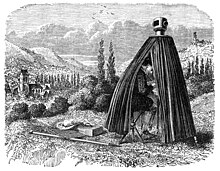

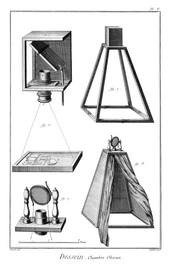

[2][3][4] Camera obscura can also refer to analogous constructions such as a darkened room, box or tent in which an exterior image is projected inside or onto a translucent screen viewed from outside.

As a drawing aid, it allowed tracing the projected image to produce a highly accurate representation, and was especially appreciated as an easy way to achieve proper graphical perspective.

[8] The human eye (and that of many other animals) works much like a camera obscura, with rays of light entering an opening (pupil), getting focused through a convex lens and passing a dark chamber before forming an inverted image on a smooth surface (retina).

[12] There are theories that occurrences of camera obscura effects (through tiny holes in tents or in screens of animal hide) inspired paleolithic cave paintings.

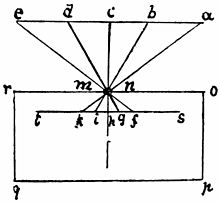

[18] The formation of pinhole images is touched upon as a subject in the work Problems – Book XV, asking: Why is it that when the sun passes through quadri-laterals, as for instance in wickerwork, it does not produce a figure rectangular in shape but circular?

However, the roundness of the image was attributed to the idea that parts of the rays of light (assumed to travel in straight lines) are cut off at the angles in the aperture become so weak that they cannot be noticed.

[23] In the 6th century, the Byzantine-Greek mathematician and architect Anthemius of Tralles (most famous as a co-architect of the Hagia Sophia) experimented with effects related to the camera obscura.

[21] In the 10th century Yu Chao-Lung supposedly projected images of pagoda models through a small hole onto a screen to study directions and divergence of rays of light.

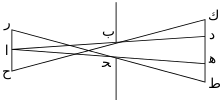

[26] Middle Eastern physicist Ibn al-Haytham (known in the West by the Latinised Alhazen) (965–1040) extensively studied the camera obscura phenomenon in the early 11th century.

Among those Ibn al-Haytham is thought to have inspired are Witelo, John Peckham, Roger Bacon, Leonardo da Vinci, René Descartes and Johannes Kepler.

[21] In his 1088 book, Dream Pool Essays, the Song dynasty Chinese scientist Shen Kuo (1031–1095) compared the focal point of a concave burning-mirror and the "collecting" hole of camera obscura phenomena to an oar in a rowlock to explain how the images were inverted:[33] "When a bird flies in the air, its shadow moves along the ground in the same direction.

[34] English philosopher and Franciscan friar Roger Bacon (c. 1219/20 – c. 1292) falsely stated in his De Multiplicatione Specerium (1267) that an image projected through a square aperture was round because light would travel in spherical waves and therefore assumed its natural shape after passing through a hole.

[35] Polish friar, theologian, physicist, mathematician and natural philosopher Vitello wrote about the camera obscura in his influential treatise Perspectiva (circa 1270–1278), which was largely based on Ibn al-Haytham's work.

[37][38] French astronomer Guillaume de Saint-Cloud suggested in his 1292 work Almanach Planetarum that the eccentricity of the Sun could be determined with the camera obscura from the inverse proportion between the distances and the apparent solar diameters at apogee and perigee.

[39] Kamāl al-Dīn al-Fārisī (1267–1319) described in his 1309 work Kitab Tanqih al-Manazir (The Revision of the Optics) how he experimented with a glass sphere filled with water in a camera obscura with a controlled aperture and found that the colors of the rainbow are phenomena of the decomposition of light.

[40][41] French Jewish philosopher, mathematician, physicist and astronomer/astrologer Levi ben Gershon (1288–1344) (also known as Gersonides or Leo de Balneolis) made several astronomical observations using a camera obscura with a Jacob's staff, describing methods to measure the angular diameters of the Sun, the Moon and the bright planets Venus and Jupiter.

He suggested to use it to view "what takes place in the street when the sun shines" and advised to use a very white sheet of paper as a projection screen so the colours would not be dull.

[48] In his influential and meticulously annotated Latin edition of the works of Ibn al-Haytham and Witelo, Opticae thesauru (1572), German mathematician Friedrich Risner proposed a portable camera obscura drawing aid; a lightweight wooden hut with lenses in each of its four walls that would project images of the surroundings on a paper cube in the middle.

The gnomon was used to study the movements of the Sun during the year and helped in determining the new Gregorian calendar for which Danti took place in the commission appointed by Pope Gregorius XIII and instituted in 1582.

Trees, forests, rivers, mountains "that are really so, or made by Art, of Wood, or some other matter" could be arranged on a plain in the sunshine on the other side of the camera obscura wall.

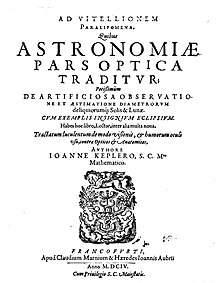

[50][56][57] The earliest use of the term camera obscura is found in the 1604 book Ad Vitellionem Paralipomena by German mathematician, astronomer, and astrologer Johannes Kepler.

[48] In 1611, Frisian/German astronomers David and Johannes Fabricius (father and son) studied sunspots with a camera obscura, after realizing looking at the Sun directly with the telescope could damage their eyes.

[63] In his 1613 book Opticorum Libri Sex[64] Belgian Jesuit mathematician, physicist, and architect François d'Aguilon described how some charlatans cheated people out of their money by claiming they knew necromancy and would raise the specters of the devil from hell to show them to the audience inside a dark room.

[66]German Orientalist, mathematician, inventor, poet, and librarian Daniel Schwenter wrote in his 1636 book Deliciae Physico-Mathematicae about an instrument that a man from Pappenheim had shown him, which enabled movement of a lens to project more from a scene through a camera obscura.

[68] Italian Jesuit philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer Mario Bettini wrote about making a camera obscura with twelve holes in his Apiaria universae philosophiae mathematicae (1642).

[71] German Jesuit scientist Gaspar Schott heard from a traveler about a small camera obscura device he had seen in Spain, which one could carry under one arm and could be hidden under a coat.

It has been widely speculated that they made use of the camera obscura,[65] but the extent of their use by artists at this period remains a matter of fierce contention, recently revived by the Hockney–Falco thesis.

[73] Johann Zahn's Oculus Artificialis Teledioptricus Sive Telescopium, published in 1685, contains many descriptions, diagrams, illustrations and sketches of both the camera obscura and the magic lantern.

These were extensively used by amateur artists while on their travels, but they were also employed by professionals, including Paul Sandby and Joshua Reynolds, whose camera (disguised as a book) is now in the Science Museum in London.

[84][85] Other contemporary visual artists who have explicitly used camera obscura in their artworks include James Turrell, Abelardo Morell, Minnie Weisz, Robert Calafiore, Vera Lutter, Marja Pirilä, and Shi Guorui.