Florence Cathedral

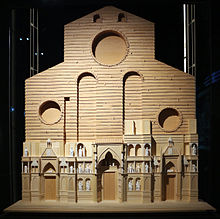

Commenced in 1296 in the Gothic style to a design of Arnolfo di Cambio and structurally completed by 1436 with the dome engineered by Filippo Brunelleschi;[1] the basilica's exterior is faced with polychrome marble panels in various shades of green and pink, bordered by white, and features an elaborate 19th-century Gothic Revival (west) façade by Emilio De Fabris.

These three buildings are part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site covering the historic centre of Florence and are a major tourist attraction of Tuscany.

[4] The ancient structure, founded in the early 5th century and having undergone many repairs, was crumbling with age, according to the 14th-century Nuova Cronica of Giovanni Villani,[5] and was no longer large enough to serve the growing population of the city.

[5] Other major Tuscan cities had undertaken ambitious reconstructions of their cathedrals during the Late Medieval period, such as Pisa and particularly Siena where the enormous proposed extensions were never completed.

The building of this vast project was to last 140 years; Arnolfo's plan for the eastern end, although maintained in concept, was greatly expanded in size.

In 1331, the Arte della Lana, the guild of wool merchants, took over patronage for the construction of the cathedral and in 1334 appointed Giotto to oversee the work.

In 1349, action resumed on the cathedral under a series of architects, starting with Francesco Talenti, who finished the campanile and enlarged the overall project to include the apse and the side chapels.

The exterior walls are faced in alternate vertical and horizontal bands of polychrome marble from Carrara (white), Prato (green), Siena (red), Lavenza and a few other places.

[21] That architectural choice, in 1367, was one of the first events of the Italian Renaissance, marking a break with the Medieval Gothic style and a return to the classic Mediterranean dome.

The spreading problem was solved by a set of four internal horizontal stone and iron chains, serving as barrel hoops, embedded within the inner dome: one at the top, one at the bottom, with the remaining two evenly spaced between them.

[20] Each of Brunelleschi's stone chains was built like an octagonal railroad track with parallel rails and cross ties, all made of sandstone beams 43 cm (17 in) in diameter and no more than 2.3 m (7.5 ft) long.

The commission for this gilt copper ball [atop the lantern] went to the sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio, in whose workshop there was at this time a young apprentice named Leonardo da Vinci.

Fascinated by Filippo's [Brunelleschi's] machines, which Verrocchio used to hoist the ball, Leonardo made a series of sketches of them and, as a result, is often given credit for their invention.

A huge statue of Brunelleschi now sits outside the Palazzo dei Canonici in the Piazza del Duomo, looking thoughtfully up towards his greatest achievement, the dome that would forever dominate the panorama of Florence.

[35] The building of the cathedral had started in 1296 with the design of Arnolfo di Cambio and was completed in 1469 with the placing of Verrochio's copper ball atop the lantern.

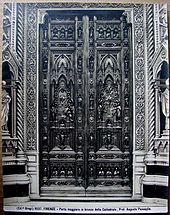

This neo-gothic façade in white, green and red marble forms a harmonious entity with the cathedral, Giotto's bell tower and the Baptistery.

Many decorations in the church have been lost in the course of time, or have been transferred to the Museum Opera del Duomo, such as the magnificent cantorial pulpits (the singing galleries for the choristers) of Luca della Robbia and Donatello.

[36] Christ crowning Mary as Queen, the stained-glass circular window above the clock, with a rich range of coloring, was designed by Gaddo Gaddi in the early 14th century.

There was also a glass-paste mosaic panel The Bust of Saint Zanobius by the 16th-century miniaturist Monte di Giovanni, but it is now on display in the Museum Opera del Duomo.

[36] Many decorations date from the 16th-century patronage of the Grand Dukes, such as the pavement in colored marble, attributed to Baccio d'Agnolo and Francesco da Sangallo (1520–26).

Originally left whitewashed following its completion it was the Grand Duke Cosimo I de' Medici who decided to have the ceiling of the dome painted.

During the restoration work, which ended in 1995, the entire pictorial cycle of The Last Judgment was photographed with specially designed equipment and all the information collected in a catalogue.

[38][39] In 1475 the Italian astronomer Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli (who was also a mathematical tutor of Brunelleschi) pierced a hole in the dome at 91.05 metres (298.7 ft) above the pavement to create a meridian line.

[40] The height precluded the installation of a complete meridian line on the floor of the cathedral, but allowed a short section of approximately 10 metres (33 ft) to run between the main altar and the north wall of the transept.

The archaeological history of this huge area was reconstructed through the work of Franklin Toker: remains of Roman houses, an early Christian pavement, ruins of the former cathedral of Santa Reparata and successive enlargements of this church.

[47] In 1955 the Opera del Duomo installed 22 mechanical deformometers, which were read four times a year to record the variations in the width of the major cracks in the inner dome.

[47][37] However analysis by Andrea Chiarugi, Michele Fanelli and Giuseppetti (published in 1983) found that the principal source of the cracks was a dead-weight effect due to the geometry of the dome, its weight (estimated to be 25,000 tons)[37] and the insufficient resistance of the ring beam, while thermal variations, has caused fatigue loading and thus expanding of the structure.

[46] In 1987 a second and more comprehensive digital system (which automatically collects data every six hours) was installed by ISMES (in cooperation with the Soprintendenza, the local branch of the Ministry of Culture, which is responsible for the conservation of all historical monuments in Florence).

It consists of 166 instruments, among which are 60 thermometers measuring the masonry and air temperature at various locations, 72 inductive type displacement transducers (deformometers) at various levels on the main cracks of the inner and outer domes; eight plumb-lines at the centre of each web, which measure the relative displacements between pillars and tambour; eight livellometers and two piezometers, one near the web 4 and the other below the nave which register the variation of the underground water level.

[50] Using software that had been used to model the structures of large dams, a computer model of the dome was developed in 1980 in a collaboration between Italian National Agency for Electric Power and Structural and Hydraulic Research Centre (CRIS) by a group of researchers led by Michele Fanelli and Gabriella Giuseppetti in cooperation with the Department of Civil Engineering of the University of Florence, under the supervision of Andrea Chiarugi.