France in the Middle Ages

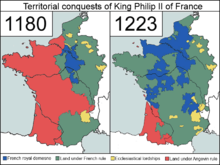

The Kingdom of France in the Middle Ages (roughly, from the 10th century to the middle of the 15th century) was marked by the fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire and West Francia (843–987); the expansion of royal control by the House of Capet (987–1328), including their struggles with the virtually independent principalities (duchies and counties, such as the Norman and Angevin regions), and the creation and extension of administrative/state control (notably under Philip II Augustus and Louis IX) in the 13th century; and the rise of the House of Valois (1328–1589), including the protracted dynastic crisis against the House of Plantagenet and their Angevin Empire, culminating in the Hundred Years' War (1337–1453) (compounded by the catastrophic Black Death in 1348), which laid the seeds for a more centralized and expanded state in the early modern period and the creation of a sense of French identity.

From the 12th and 13th centuries on, France was at the center of a vibrant cultural production that extended across much of western Europe, including the transition from Romanesque architecture to Gothic architecture and Gothic art; the foundation of medieval universities (such as the universities of Paris (recognized in 1150), Montpellier (1220), Toulouse (1229), and Orleans (1235)) and the so-called "Renaissance of the 12th century"; a growing body of secular vernacular literature (including the chanson de geste, chivalric romance, troubadour and trouvère poetry, etc.)

The Gallo-Romance group in the north of France, consisting of langues d'oïl such as Picard, Walloon, and Francien, were influenced by Germanic languages spoken by the earliest Frankish invaders.

From the 4th to 7th centuries, Brythonic-speaking peoples from Cornwall, Devon, and Wales travelled across the English Channel, both for reasons of trade and of flight from the Anglo-Saxon invasions of England, and established themselves in Armorica in northwest France.

By the end of the 15th century, serfdom was largely extinct;[20] henceforth "free" peasants paid rents for their own lands, and the lord's demesne was worked by hired labor.

In addition to these, there also existed zones with an extended urban network of medium to small cities, as in the south and the Mediterranean coast (from Toulouse to Marseille, including Narbonne and Montpellier) and in the north (Beauvais, Laon, Amiens, Arras, Bruges, etc.).

[31] With traditions going back to the Romans; one was "noble" if he or she possessed significant land holdings, had access to the king and royal court, could receive honores and benefices for service (such as being named count or duke).

First off, the aristocracy increasingly focused on establishing strong regional bases of landholdings,[33] on taking hereditary control of the counties and duchies,[34] and eventually on erecting these into veritable independent principalities[35] and privatizing various privileges and rights of the state.

[42] In its origin, the feudal grant had been seen in terms of a personal bond between lord and vassal, but with time and the transformation of fiefs into hereditary holdings, the nature of the system came to be seen as a form of "politics of land" (an expression used by the historian Marc Bloch).

The 11th century in France saw what has been called by historians a "feudal revolution" or "mutation" and a "fragmentation of powers" (Bloch) that was unlike the development of feudalism in England or Italy or Germany in the same period or later:[43] counties and duchies began to break down into smaller holdings as castellans and lesser seigneurs took control of local lands, and (as comital families had done before them) lesser lords usurped/privatized a wide range of prerogatives and rights of the state, most importantly the highly profitable rights of justice, but also travel dues, market dues, fees for using woodlands, obligations to use the lord's mill, etc.

Since the peers were never twelve during the coronation in early periods, due to the fact that most lay peerages were forfeited to or merged in the crown, delegates were chosen by the king, mainly from the princes of the blood.

The 11th century in France marked the apogee of princely power at the expense of the king when states like Normandy, Flanders or Languedoc enjoyed a local authority comparable to kingdoms in all but name.

Over the centuries, the number of jurists (or "légistes"), generally educated by the université de Paris, steadily increased as the technical aspects of the matters studied in the council mandated specialized counsellers.

In 1256, Saint Louis issued a decree ordering all mayors, burghesses, and town councilmen to appear before the King's sovereign auditors of the Exchequer (French gens des comptes) in Paris to render their final accounts.

Thereafter, the financial specialists received accounts for audit in a room of the royal palace that became known as the Camera compotorum or Chambre des comptes, and they began to be collectively identified under the same name, although still only a subcommission of the King's Court, consisting of about sixteen people.

In 1302, expanding French royal power led to a general assembly consisting of the chief lords, both lay and ecclesiastical, and the representatives of the principal privileged towns, which were like distinct lordships.

Certain precedents paved the way for this institution: representatives of principal towns had several times been convoked by the king, and under Philip III there had been assemblies of nobles and ecclesiastics in which the two orders deliberated separately.

To monitor the performance and curtail abuses of the prévôts or their equivalent (in Normandy a vicomte, in parts of northern France a châtelain, in the south a viguier or a bayle), Philip II Augustus, an able and ingenious administrator who founded many of the central institutions on which the French monarchy's system of power would be based, established itinerant justices known as baillis ("bailiff") based on medieval fiscal and tax divisions which had been used by earlier sovereign princes (such as the Duke of Normandy).

Provosts therefore retained the sole function of inferior judges over vassals with original jurisdiction concurrent with bailies over claims against nobles and actions reserved for royal courts (cas royaux).

The area around the lower Seine, ceded to Scandinavian invaders as the Duchy of Normandy in 911, became a source of particular concern when Duke William took possession of the kingdom of England in the Norman Conquest of 1066, making himself and his heirs the King's equal outside France (where he was still nominally subject to the Crown).

The 13th century was to bring the crown important gains also in the south, where a papal-royal crusade against the region's Albigensian or Cathar heretics (1209) led to the incorporation into the royal domain of Lower (1229) and Upper (1271) Languedoc.

However, Philip III's attempted crusade against Aragon, a blatantly political affair, ended in disaster as an epidemic struck his army, which then was soundly defeated by Aragonese forces at Col de Panissars.

Of the later Capetian rulers, Philip IV was the greatest, bringing royal power to the strongest level it would attain in the Middle Ages, yet alienated a great many people and generally left France exhausted.

With all this, the king could now assert power nearly anywhere in France, yet there was still a great deal of work yet to be done and French rulers for the time being continued to do without Brittany, Burgundy, and numerous lesser territories although they legislated for the whole realm.

In 1301, fresh trouble erupted when the Bishop of Pamiers was accused by the King of heresy and treason, leading to another protest from Boniface VIII that Church property could not be confiscated without Rome's permission and all Christian rulers were subordinate to papal authority.

The Templars had been founded during the Crusades more than a century earlier, but now consisted of old men whose prestige was greatly diminished after the fall of the Holy Land and no longer seemed to serve any useful purpose worth their privileges.

Louis died in the summer of 1316 at only 26 of an unknown illness (possibly gastroenteritis) after consuming a large quantity of chilled wine following a game of tennis on an extremely hot day.

He made plans for a new crusade to relieve the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, but the Flanders situation remained unstable and an attempted French naval expedition to the Middle East was destroyed off Genoa in 1319.

Having put an end to the chaos in southern France that his brother faced, he turned his attention to Flanders, but then a revolt broke out in Gascony over the unwelcome construction of a fortress on the border by a French vassal.

Reconciliation in 1435 between the king and Philippe the Good, duke of Burgundy, removed the greatest obstacle to French recovery, leading to the recapture of Paris (1436), Normandy (1450) and Guienne (1453), reducing England's foothold to a small area around Calais (lost also in 1558).