Societal effects of cars

Automobiles provide easier access to remote places and mobility, in comfort, helping people to geographically widen their social and economic interactions.

Although the introduction of the mass-produced car represented a revolution in industry and convenience,[1][2] creating job demand and tax revenue, the high motorisation rates also brought severe consequences to the society and to the environment.

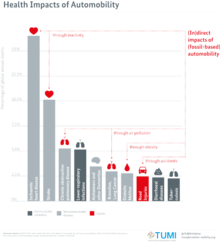

The modern negative associations with heavy automotive use include the use of non-renewable fuels, a dramatic increase in the rate of accidental death, the disconnection of local community,[3][4] the decrease of local economy,[5] the rise in cardiovascular diseases, the emission of air and noise pollution, the emission of greenhouse gases, generation of urban sprawl and traffic, segregation of pedestrians and other active mobility means of transport, decrease in the railway network, urban decay, and the high cost per unit-distance of private transport.

Hence, neglecting the negative externalities of private automobility is irresponsible, and replacing combustion engine vehicles with EVs is merely a strategy to lose more slowly from social and environmental points of view.

Not only would this provide a speedy and effective punishment for the erring motorist, but it would also supply the dwellers on popular high roads with a comfortable increase of income.

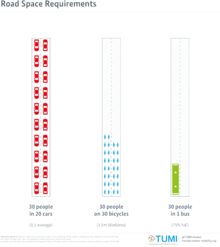

The resulting traffic congestion and urban sprawl has brought an increase in average journey times in large cities, and the decommissioning of older tram systems.

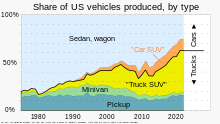

[20] Certain developments in retail are partially due to car use, such as supermarket growth, drive-thru fast food purchasing, and gasoline station grocery shopping as well.

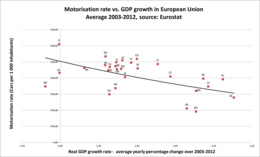

Several auto-dependent countries, lacking an automobile industry and oil wells, must import vehicles and fuel, affecting their commercial balance.

In Denmark, cycling policies were adopted as a direct consequence of the 1973 oil crisis, whereas bike advocacy in the Netherlands started in earnest with a campaign against traffic deaths called "stop child murder".

Because cars did not require rest, were faster than horse-drawn conveyances, and soon had a lower total cost of ownership, more people were routinely able to travel farther than in earlier times.

[30] Beginning in the 1940s, most urban environments in the United States lost their streetcars, cable cars, and other forms of light rail, to be replaced by diesel-run motor coaches or buses.

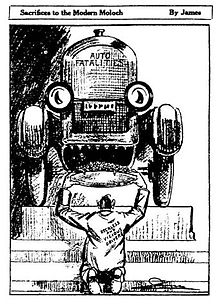

With the proliferation of the car, a pedestrian has to anticipate safety risks of automobiles traveling at high speeds because they can cause serious injuries to a human and can be fatal,[21] unlike in previous times when traffic deaths were usually due to horses escaping control.

[citation needed] Following World War II in the United States, government policies and regulations such as the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, low-cost mortgages through the G.I.

The automotive industry was also under attack from bureaucratic fronts, and new emission and CAFÉ regulations began to hamper Big Three (automobile manufacturers) profit margins as the United States went into a recession.

In combination with his second book On the Nature of Cities (1979), he called for a struggle to halt and partially reverse negative developments in transportation, although he was largely ignored at the time.

The 1973 Arab-Israeli War was followed by the OPEC oil embargo, leading to an explosion of prices, long queues at filling stations, and talks of rationing fuel.

While it may appear clear, in retrospect, that the automotive/suburban culture would continue to persist, as it did in the 1950s and 1960s, no such certainty existed at the time when British architect Martin Pawley authored his seminal work, The Private Future (1973).

Pawley called the automobile "the shibboleth of privatisation; the symbol and the actuality of withdrawal from the community" and perceived that, in spite of its momentary misfortunes, its dominance in North American society would continue.

[36] The American Motor League had promoted the making of more and better cars since the early days of the car, and the American Automobile Association joined the good roads movement begun during the earlier bicycle craze; when manufacturers and petroleum fuel suppliers were well established, they also joined construction contractors in lobbying governments to build public roads.

Cheap restaurants and motels appeared on favorite routes and provided wages for locals who were reluctant to join the trend to rural depopulation.

In Europe, massive freeway building programs were initiated by a number of social democratic governments after World War II, in an attempt to create jobs and make the car available to the working classes.

[citation needed] The 1973 oil crisis and with it fuel rationing measures brought to light for the first time in a generation, what cities without cars might look like, reinvigorating or creating environmental consciousness in the process.

Green parties emerged in several European countries in partial response to car culture, but also as the political arm of the anti-nuclear movement.

Many prestigious social events around the world today are centered around the hobby, a notable example is the Pebble Beach Concours d'Elegance classic car show.

[45][failed verification] It is estimated that motor vehicle collisions caused the death of around 60 million people during the 20th century[46] around the same number of World War II casualties.

[48] Besides improving general road conditions like lighting and separated walkways, Japan has been installing intelligent transportation system technology such as stalled-car monitors to avoid crashes.

In countries such as the United States the infrastructure that makes car use possible, such as highways, roads and parking lots is funded by the government and supported through zoning and construction requirements.

This government support of the automobile through subsidies for infrastructure, the cost of highway patrol enforcement, recovering stolen cars, and many other factors makes public transport a less economically competitive choice for commuters when considering out-of-pocket expenses.

In 2013, annual car ownership costs including repair, insurance, gas and taxes were highest in Georgia ($4,233) and lowest in Oregon ($2,024) with a national average of $3,201.

The Austrian philosopher Ivan Illich, a critic of the modern society habits, was one of the first thinkers to establish the so-called consumer speed concept.