Carcharodontosaurus

'jagged toothed lizard') is a genus of large carnivorous theropod dinosaur that lived in Northwest Africa from about 100 to 94 million years ago during the Cenomanian age of the Cretaceous.

A partial skeleton initially referred to this genus was collected by crews of German paleontologist Ernst Stromer during a 1914 expedition to Egypt.

Its jaws were lined with sharp, recurved, serrated teeth that bear striking resemblances to those of the great white shark (genus Carcharodon), the inspiration for the name.

Many gigantic theropods are known from North Africa during this period, including both species of Carcharodontosaurus as well as the spinosaurid Spinosaurus, the possible ceratosaur Deltadromeus and unnamed large abelisaurids.

North Africa at the time was blanketed in mangrove forests and wetlands, creating a hotspot of fish, crocodyliforms, and pterosaur diversity.

In 1925, Depéret and his colleague Justin Savornin described the teeth as syntypes (name-bearing specimens) of a new species of theropod dinosaur, Megalosaurus saharicus.

[11][1] However, fossils referred to C. saharicus were first found in marls near Ain Gedid, Egypt in early April 1914 by Austro-Hungarian paleontologist Richard Markgraf.

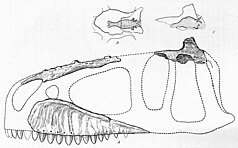

This Egyptian skeleton (SNSB-BSPG 1922 X 46) consisted of a partial skull, including much of the braincase, teeth, three cervical and a caudal vertebra, incomplete pelvis, a manual ungual, femora, and the left fibula.

However, he found it necessary to erect a new genus for this species, Carcharodontosaurus, for their similarities, in sharpness and serrations, to the teeth of the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias).

[13] World War II would break out in 1939, leading SNSB-BSPG 1922 X 46 and other material from Bahariya to be destroyed during a British bombing raid on Munich during the night of April 24/25, 1944.

[15] Few discoveries of Carcharodontosaurus material were made until 1995, when American paleontologist Paul Sereno found an incomplete skull during an expedition embarked on by the University of Chicago.

[7] In 2007, SGM-Din 1 was officially designated as the neotype of C. saharicus due to the loss of other specimens and the similar age and geographic location to previously noted material.

[9] The taxonomy of Carcharodontosaurus was discussed by Chiarenza and Cau (2016),[20] who suggested that the neotype of C. saharicus was similar but distinct from the holotype in the morphology of the maxillary interdental plates.

Several other remains such as a braincase, a lacrimal, a dentary, a cervical vertebra, and a collection of teeth were referred to C. iguidensis based on size and supposed similarities to other Carcharodontosaurus bones.

[20] Stromer hypothesized that C. saharicus was around the same size as the tyrannosaurid Gorgosaurus, which would place it at around 8–9 metres (26–30 ft) long, based on his specimen SNSB-BSPG 1922 X 46 (now Tameryraptor).

The lower jaw articulation was placed farther back behind the occipital condyle (where the neck is attached to the skull) compared to other theropods.

[7] Two dentary (lower jaw bone) fragments which were referred to C. saharicus by Ibrahim et al. (2020) have deep and expanded alveoli (tooth sockets), traits found in other large theropods.

In life, the floccular lobe of the brain would have projected into the area surrounded by the semicircular canals, just like in other non-avian theropods, birds, and pterosaurs.

Carcharodontosauridae was a clade created by Stromer for Carcharodontosaurus and Bahariasaurus, though the name remained unused until the recognition of other members of the group in the late 20th century.

He noted the likeness of Carcharodontosaurus bones to the American theropods Allosaurus and Tyrannosaurus, leading him to consider the family part of Theropoda.

The results of their analysis using merged OTUs (operational taxonomic units) is displayed in the cladogram below:[15] Lusovenator Lajasvenator Carcharodontosaurus iguidensis Taurovenator Tyrannotitan Rodolfo Coria and Leonardo Salgado suggested that the convergent evolution of gigantism in theropods could have been linked to common conditions in their environments or ecosystems.

Dispersal routes between the northern and southern continents appear to have been severed by ocean barriers in the Late Cretaceous, which led to more distinct, provincial faunas, by preventing exchange.

[65][7] Previously, it was thought that the Cretaceous world was biogeographically separated, with the northern continents being dominated by tyrannosaurids, South America by abelisaurids, and Africa by carcharodontosaurids.

[66] The subfamily Carcharodontosaurinae, in which Carcharodontosaurus belongs, appears to have been restricted to the southern continent of Gondwana (formed by South America and Africa), where they were probably the apex predators.

[75] Isotopic analyses of the teeth of C. saharicus have found δ18O values that are higher than that of the contemporary Spinosaurus, suggesting the latter pursued semi-aquatic habits whereas Carcharodontosaurus was more terrestrial.

[79] A 2006 study by biologist Kent Stevens analyzed the binocular vision capabilities of the allosauroids Carcharodontosaurus and Allosaurus as well as several coelurosaurs including Tyrannosaurus and Stenonychosaurus.

By applying modified perimetry to models of these dinosaurs' heads, Stevens deduced that the binocular vision of Carcharodontosaurus was limited, a side effect of its large, elongated rostrum.

[80] The neotype skull of C. saharicus is one of many allosauroid individuals to preserve pathologies, with signs of biting, infection, and breaks observed in Allosaurus and Acrocanthosaurus among others.

[21][7] North Africa during this period bordered the Tethys Sea, which transformed the region into a mangrove-dominated coastal environment filled with vast tidal flats and waterways.

[87] This led to an abundance of piscivorous crocodyliformes evolving in response, such as the giant stomatosuchid Stomatosuchus in Egypt and the genera Elosuchus, Laganosuchus, and Aegisuchus from Morocco.