Library catalog

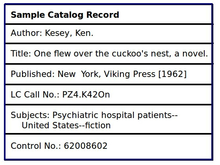

A bibliographic item can be any information entity (e.g., books, computer files, graphics, realia, cartographic materials, etc.)

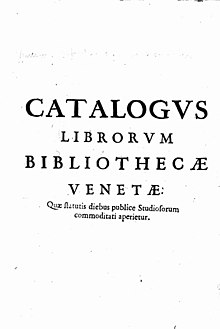

The earliest library catalogs were lists, handwritten or enscribed on clay tablets and later scrolls of parchment or paper.

[4] Antonio Genesio Maria Panizzi in 1841[5] and Charles Ammi Cutter in 1876[6] undertook pioneering work in the definition of early cataloging rule sets formulated according to theoretical models.

Cutter made an explicit statement regarding the objectives of a bibliographic system in his Rules for a Printed Dictionary Catalog.

It solved the problems of the structural catalogs in marble and clay from ancient times and the later codex—handwritten and bound—catalogs that were manifestly inflexible and presented high costs in editing to reflect a changing collection.

[12] In November 1789, during the dechristianization of France during the French Revolution, the process of collecting all books from religious houses was initiated.

[13][14]: 30–31 English inventor Francis Ronalds began using a catalog of cards to manage his growing book collection around 1815, which has been denoted as the first practical use of the system.

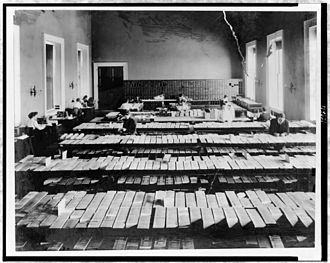

Very shortly afterward, Melvil Dewey and other American librarians began to champion the card catalog because of its great expandability.

Melvil Dewey saw well beyond the importance of standardized cards and sought to outfit virtually all facets of library operations.

To the end he established a Supplies Department as part of the ALA, later to become a stand-alone company renamed the Library Bureau.

In one of its early distribution catalogs, the bureau pointed out that "no other business had been organized with the definite purpose of supplying libraries".

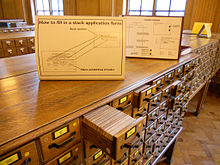

With a focus on machine-cut index cards and the trays and cabinets to contain them, the Library Bureau became a veritable furniture store, selling tables, chairs, shelves and display cases, as well as date stamps, newspaper holders, hole punchers, paper weights, and virtually anything else a library could possibly need.

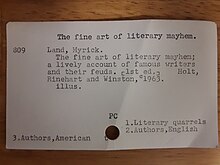

If it was a non-fiction record, Charles A. Cutter's classification system would help the patron find the book they wanted in a quick fashion.

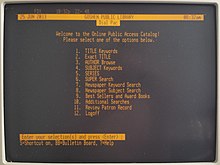

Cutter's classification system is as follows:[19] Some libraries with OPAC access still have card catalogs on site, but these are now strictly a secondary resource and are seldom updated.

Some libraries have eliminated their card catalog in favor of the OPAC for the purpose of saving space for other use, such as additional shelving.

The seventh century BCE Babylonian Library of Ashurbanipal was led by the librarian Ibnissaru who prescribed a catalog of clay tablets by subject.

The task of recording the contents of libraries is more than an instinct or a compulsive tic exercised by librarians; it began as a way to broadcast to readers what is available among the stacks of materials.

[citation needed] As librarian, Gottfried van Swieten introduced the world's first card catalog (1780) as the Prefect of the Imperial Library, Austria.

card for personal filing systems, enabling much more flexibility, and toward the end of the 20th century the online public access catalog was developed (see below).

An equivalent scheme in the United Kingdom was operated by the British National Bibliography from 1956[23] and was subscribed to by many public and other libraries.

Simply put, authority control is defined as the establishment and maintenance of consistent forms of terms – such as names, subjects, and titles – to be used as headings in bibliographic records.