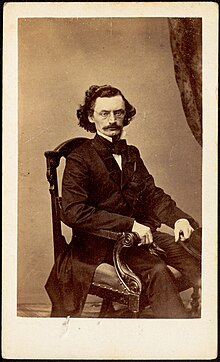

Carl Schurz

Born in the Kingdom of Prussia's Rhine Province, Schurz fought for democratic reforms in the German revolutions of 1848–1849 as a member of the academic fraternity association Deutsche Burschenschaft.

He also became a strong advocate for the anti-slavery movement and joined the newly organized Republican Party, unsuccessfully running for Lieutenant Governor of Wisconsin.

Schurz chaired the 1872 Liberal Republican convention, which nominated a ticket that unsuccessfully challenged President Grant in the 1872 presidential election.

Schurz sought to make civil service based on merit rather than political and party connections and helped prevent the transfer of the Bureau of Indian Affairs to the War Department.

He remained active in politics and led the "Mugwump" movement, which opposed nominating James G. Blaine in the 1884 presidential election.

He joined the nationalistic Studentenverbindung Burschenschaft Franconia at Bonn, which at the time included among its members Friedrich von Spielhagen, Johannes Overbeck, Julius Schmidt, Carl Otto Weber, Ludwig Meyer and Adolf Strodtmann.

[6][7] In response to the early events of the revolutions of 1848, Schurz and Kinkel founded the Bonner Zeitung, a paper advocating democratic reforms.

[8] When the Frankfurt rump parliament called for people to take up arms in defense of the new German constitution, Schurz, Kinkel, and others from the University of Bonn community did so.

During this struggle, Schurz became acquainted with Franz Sigel, Alexander Schimmelfennig, Fritz Anneke, Friedrich Beust, Ludwig Blenker and others, many of whom he would meet again in the Union Army during the U.S. Civil War.

[10] While in London, Schurz married fellow revolutionary Johannes Ronge's sister-in-law, Margarethe Meyer, in July 1852 and then, like many other Forty-Eighters, migrated to the United States.

[5] Living initially in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the Schurzes moved to Watertown, Wisconsin, where Carl nurtured his interests in politics and Margarethe began her seminal work in early childhood education.

In Faneuil Hall, Boston, on April 18, 1859,[12] he delivered an oration on "True Americanism", which, coming from an alien, was intended to clear the Republican party of the charge of "nativism".

In June, he took command of a division, first under John C. Frémont, and then in Franz Sigel's corps, with which he took part in the Second Battle of Bull Run in August 1862.

Containing several German-American units, the XI Corps performance during both battles was heavily criticized by the press, fueling anti-immigrant sentiments.

[15] The report was ignored by the President, but it helped fuel the movement pushing for a larger congressional role in Reconstruction and holding Southern states to higher standards.

[citation needed] During this period, he broke with the Grant administration, starting the Liberal Republican movement in Missouri, which in 1870 elected B. Gratz Brown governor.

Schurz was identified with the committee's investigation of arms sales to and cartridge manufacture for the French army by the United States government during the Franco-Prussian War.

During Reconstruction, Schurz was opposed to federal military enforcement and protection of African American civil rights, and held nineteenth century ideas of European superiority and fears of miscegenation.

[17][18] In 1870, Schurz helped form the Liberal Republican Party, which opposed President Ulysses S. Grant's annexation of Santo Domingo and his use of the military to destroy the Ku Klux Klan in the South under the Enforcement Acts.

Grant won by a landslide, and Greeley died shortly after election day in November, before the Electoral College had even met.

[20] Promises made to Indian chiefs at White House meetings with President Rutherford B. Hayes and Schurz were often broken.

In this department, Schurz put into force his belief that merit should be the principal consideration in appointing people to jobs in the Civil Service.

[10] During Schurz's tenure as Secretary of the Interior, a movement to transfer the Office of Indian Affairs to the control of the War Department began, assisted by the strong support of Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman.

That year German-born Henry Villard, president of the Northern Pacific Railway, acquired the New York Evening Post and The Nation and turned the management over to Schurz, Horace White and Edwin L.

In 1892, he succeeded George William Curtis as president of the National Civil Service Reform League and held this office until 1901.

[28] True to his anti-imperialist convictions, Schurz exhorted McKinley to resist the urge to annex land following the Spanish–American War.

[29] He authored an opinion piece warning that prominent imperialists would take in "Spanish- Americans, with all the mixtures of Indian and negro blood, and Malays and other unspeakable Asiatics, by the tens of millions!

[31] Carl Schurz lived in a summer cottage in Northwest Bay on Lake George, New York which was built by his good friend Abraham Jacobi.