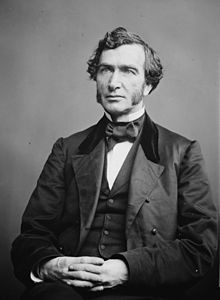

John Sherman

As a senator, he was a leader in financial matters, helping to redesign the United States' monetary system to meet the needs of a nation torn apart by civil war.

Serving as Secretary of the Treasury in the administration of Rutherford B. Hayes, Sherman continued his efforts for financial stability and solvency, overseeing an end to wartime inflationary measures and a return to gold-backed money.

[15] In 1852, Sherman was again a delegate to the Whig National Convention, where he supported the eventual nominee, Winfield Scott, against rivals Daniel Webster and incumbent Millard Fillmore, who had become president following Taylor's death.

[21] Preventing the expansion of slavery to Kansas was the one issue that united Banks's fragile majority, and the House resolved to send three members to investigate the situation in that territory; Sherman was one of the three selected.

In March 1857, the Supreme Court issued its decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, holding that Congress had no power to prevent slavery in the territories and that blacks—whether free or enslaved—could not be citizens of the United States.

[29] In December of that year, in an election boycotted by free-state partisans, Kansas adopted the pro-slavery Lecompton Constitution and petitioned Congress to be admitted as a slave state.

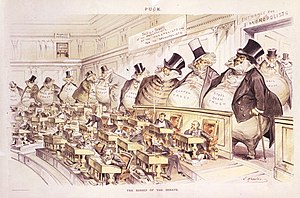

[33] Citing the need to pare unnecessary expenditures in light of diminished revenue, Sherman especially criticized Southern senators for adding appropriations to the House's bills.

[39] The election for Speaker was sidetracked immediately by a furor over an anti-slavery book, The Impending Crisis of the South, written by Hinton Rowan Helper and endorsed by many Republican members.

[55] The Civil War expenditures quickly strained the government's already fragile financial situation and Sherman, assigned to the Senate Finance Committee, was involved in the process of increasing the revenue.

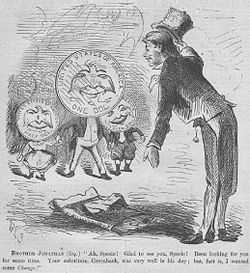

Sherman understood that "a radical change in existing laws relating to our currency must be made, or ... the destruction of the Union would be unavoidable ..."[64] Secretary Chase agreed and proposed that the Treasury Department issue United States Notes that were redeemable not in specie but in 6% government bonds.

[66] The idea of making paper money legal tender was controversial, and William Pitt Fessenden of Maine, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, was among many who opposed the proposal.

He defended his position as necessary in his memoirs, saying "from the passage of the legal tender act, by which means were provided for utilizing the wealth of the country in the suppression of the rebellion, the tide of war turned in our favor".

[92] Most Senate Finance Committee members had no objection, and Sherman found himself alone in opposition to it, believing that withdrawing greenbacks from circulation would contract the money supply and harm the economy.

[90] In his memoirs, Sherman called this law "the most injurious and expensive financial measure ever enacted by Congress," as the continued high-interest payments it required "added fully $300,000,000 of interest" to the national debt.

[105] Sherman emphasized in his memoirs that the bill was openly debated for several years and passed both Houses with overwhelming support and that, given the continued circulation of smaller silver coins at the same 16:1 ratio, nothing had been "demonetized," as his opponents claimed.

On the other hand, later scholars have suggested that Sherman and others wished to demonetize silver for years and move the country onto a gold-only standard of currency—not for some corrupt gain, but because they believed it was the path to a strong, secure currency.

[109] Farmers and laborers, especially, clamored for the return of coinage in both metals, believing the increased money supply would restore wages and property values, and the divide between pro- and anti-silver forces grew in the decades to come.

[110] Writing in 1895, Sherman defended the bill, saying that, barring some international agreement to switch the entire world to a bimetallic standard, the United States dollar should remain a gold-backed currency.

[119] The issue of specie payments was debated in the campaign, with Hayes endorsing Sherman's position and his Democratic opponent, incumbent Governor William Allen, in favor of increased circulation of greenbacks redeemable in bonds.

[123] Sherman, by this time thoroughly displeased with Grant and his administration, nonetheless took up the call in the name of party loyalty, joining James A. Garfield, Stanley Matthews, and other Republican politicians in Louisiana a few days later.

Democratic Representative Richard P. Bland of Missouri proposed a bill that would require the United States buy as much silver as miners could sell the government and strike it into coins, a system that would increase the money supply and aid debtors.

[135] "In view of the strong public sentiment in favor of the free coinage of the silver dollar", he later wrote, "I thought it better to make no objections to the passage of the bill, but I did not care to antagonize the wishes of the President.

[141] Hayes issued an executive order that forbade federal office holders from being required to make campaign contributions or otherwise taking part in party politics.

[160] He spoke on behalf of Ohio Governor Charles Foster's effort for a second term and went to Kenyon College with ex-President Hayes, where he received an honorary degree.

After completing a long-planned visit to Yellowstone National Park and other Western sites with his brother William, Sherman returned to a second special session of Congress in October 1881.

[172] Sherman opposed both the 1880 treaty revisions and the bill Miller proposed, believing that the Exclusion Act reversed the United States' traditional welcoming of all people and the country's dependence on foreign immigration for growth.

[210] Academic debate continues over the efficacy of the bond issues, but the consensus is that the repeal of the Silver Purchase Act was, at worst, unharmful and, at best, useful in restoring the nation's financial health.

Sherman believed there was a lot America could learn from England as an example with respects to economic systems, railroads and governance, and he was fond of highlighting the English origins of American political thought.

[219] The appointment was seen as a good one, but many in Washington soon began to question whether Sherman, at age 73, still had the strength and intellectual vigor to handle the job; rumors circulated to that effect, but McKinley did not believe them.

Burton, in summing up his subject, wrote: It is true that there was much that was prosaic in the life of Sherman, and that his best efforts were not connected with that glamour which gains the loudest applause; but in substantial influence upon those characteristic features which have made this country what it is, and in the unrecognized but permanent results of efficient and patriotic service for its best interests, there are few for whom a more beneficial record can be claimed.