California Trail

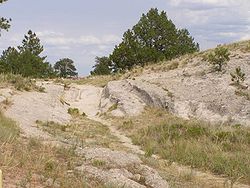

About 1,000 miles (1,600 km) of the rutted traces of these trails remain in Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, Nevada, and California as historical evidence of the great mass migration westward.

Trapper Jim Beckwourth describes: "Mirth, songs, dancing, shouting, trading, running, jumping, singing, racing, target-shooting, yarns, frolic, with all sorts of drinking and gambling extravagances that white men or Indians could invent.

[7] His return route from California went across the southern Sierra mountains via what's named now Walker Pass—named by U.S. Army topographic engineer, explorer, adventurer, and map maker John C. Frémont.

The Humboldt River with its water and grass needed by the livestock (oxen, mules horses and later cattle) and emigrants provided a key link west to northern California.

In July 1836, missionary wives Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding were the first white pioneer women to cross South Pass on their way to Oregon Territory via Fort Hall.

They left Missouri with 69 people and reasonably easily reached the future site of Soda Springs, Idaho on the Bear River by following experienced trapper Thomas "Broken-hand" Fitzpatrick on his way to Fort Hall.

[17] From Carson pass they followed the northern Sierra's southern slopes, to minimize snow depth, of what is now called the American River Valley down to Sutter's Fort located near what is now Sacramento, California.

All of the Hastings Cutoffs to California were found to be very hard on the wagons, livestock and travelers as well as being longer, harder, and slower to traverse than the regular trail and was largely abandoned after 1846.

In 1834 Benjamin Bonneville, a United States Army officer on leave to pursue an expedition to the west financed by John Jacob Astor, sent Joseph R. Walker and a small horse mounted party westward from the Green River in present-day Wyoming.

Fremont and his men, led by his guide and former trapper Kit Carson, made extensive expeditions starting in 1844 over parts of California and Oregon including the important Humboldt River and Old Spanish Trail routes.

[27] 1849 was also the first year of large scale cholera epidemics in the United States and the rest of the world, and thousands are thought to have died along the trail on their way to California—most buried in unmarked graves in Kansas and Nebraska.

The wheels were greased with a mixture of tar or pine resin and lard contained in a covered wooden bucket or large ox horn often hanging from the rear axle to keep its greasy contents away from other goods.

Horses were often found to be incapable of the months of daily work and poor feed encountered without using supplemental grain (initially unavailable or too heavy), and thousands were recorded as dying near the end of the trip in the Forty Mile Desert.

Ex-trappers, ex-army soldiers and Indians often used pemmican made by pounding jerky until it was a coarse meal, putting it into a leather bag and then pouring rendered fat (and sometimes pulverized dried berries) over it—this was very light weight, could keep for months and provided a lot of energy.

The wagons and their teams were the ultimate "off road" equipment in their time and were able to traverse incredibly steep mountain ranges, gullies, large and small streams, forests, brush, and other rough country.

Many emigrants from the eastern seaboard traveled from the east coast across the Allegheny Mountains to Brownsville, Pennsylvania (a barge building and outfitting center) or Pittsburgh and thence down the Ohio River on flatboats or steamboats to St. Louis, Missouri.

Once the water supplies became contaminated, because the cholera bacillus is zoophilic (it can infect birds, various mammals, and live in micro-organisms) it could easily spread and remain a threat along much of the Trail.

Later settlers who had crossed to the northern side of the river at Casper would come to favor a route through a small valley called Emigrant Gap which headed directly to Rock Avenue, bypassing Red Buttes.

Expeditions under the command of Frederick W. Lander surveyed a new route starting at Burnt Ranch following the last crossing of the Sweetwater River before it turned west over South Pass.

From Smoot, the road then continued north about 20 miles (32 km) down Star Valley west of the Salt River before turning almost due west at Stump Creek near the present town of Auburn, Wyoming and passing into the present state of Idaho and following the Stump Creek valley about ten miles (16 km) northwest over the Caribou Mountains (Idaho) (this section of the trail is now accessible only by US Forest Service path as the main road (Wyoming Highway 34) now goes through Tincup canyon to get across the Caribous.)

On March 2, 1861, before the American Civil War had actually begun at Fort Sumter, the United States Government formally revoked the contract of the Butterfield Overland Stagecoach Company in anticipation of the coming conflict.

The desert covered an area of over 70 by 150 miles (110 by 240 km), forming a fire box: its loose, white, salt-covered sands and baked alkali clay wastes reflected the sun's heat onto the stumbling travelers and animals.

After hitting the Truckee River just as it turned almost due north towards Pyramid Lake near today's Wadsworth, Nevada, the emigrants had crossed the dreaded Forty Mile Desert.

Beginning in 1860 and continuing for some nine years, the road underwent major improvements, becoming one of the busiest trans-Sierra trails being favored by teamsters and stage drivers over the Placerville Route (Johnson Cutoff) because of its lower elevations, easier grades, and access to ship cargo.

[111] They followed Iron Mountain Ridge southeast of what is now Placerville, California (there were essentially no settlements east of Sutter's Fort in 1848) before hitting Tragedy Spring near Silver Lake.

Travelers heading west in 1848 and later, crossed Forty Mile Desert, then followed the trail blazed by the Mormons in 1848 up the Carson River valley from what is now Fallon, Nevada, in 1850 the town was called "Ragtown".

Winter and its attendant runoffs raised havoc with the road and in spring 1860, when the mobs were trying to get to Virginia City, Nevada, and the new Comstock Lode strike, it was reported as a barely passably trail in places (April 1860).

To help the emigrants leaving the main trail at Lassen's meadow and going to Honey Lake, Lander had two large reservoir tanks built at Rabbit Hole and Antelope Springs.

During summer daylight hours, the roads were often packed for miles in busy spots with heavily laden wagons headed east and west usually pulled by up to ten mules.

The ongoing massive needs for millions of board feet of Sierra timber and thousands of cords of firewood in the Comstock Lode mines and towns would be the single major exception, although they even built narrow gauge railroads to haul much of this.