Casey Jones

All are agreed, however, that Jones managed to avert a potentially disastrous crash through his exceptional skill at slowing the engine and saving the lives of the passengers at the cost of his own.

[8] In the summer of 1887, a yellow fever epidemic struck many train crews on the neighboring Illinois Central Railroad (IC), providing an unexpected opportunity for faster promotion of firemen on that line.

[7] During the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois, in 1893, IC was charged with providing commuter service for the thousands of visitors to the fairground.

He had left the cab with a fellow engineer Bob Stevenson, who had reduced speed sufficiently for Jones to walk safely out on the running board to oil the relief valves.

He had finished well before they arrived at the station, as planned, and was returning to the cab when he noticed a group of small children dart in front of the train some 60 yards (55 m) ahead.

Realizing that she was still immobile, he raced to the tip of the pilot (cowcatcher) and braced himself on it, reaching out as far as he could to pull the frightened but unharmed girl from the rails.

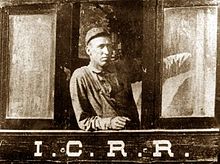

He was by all accounts an ambitious engineer, eager to move up the seniority ranks and serve on the better-paying, more prestigious passenger trains.

[7] Engineer Willard W. "Bill" Hatfield had transferred from Memphis back to a run out of Water Valley, thus opening up trains No.

In the account given in the book Railroad Avenue by Freeman H. Hubbard, which was based on an interview with fireman Sim Webb, he and Casey had been used extra on trains 3 and 2 to cover for engineer Sam Tate, who had marked off ill.

With 25 miles (40 km) of fast track ahead, Jones likely felt he had a good chance to make it to Canton by 4:05 am "on the advertised".

72, a long freight train (located to the south and headed north), were both on the passing track to the east of the main line.

72 to move northward and pull its overlapping cars off the main line and onto the east side track from the south switch.

Sim then stepped down the ladder on Casey's side of the engine, crouched, and flung himself into the darkness an estimated 300 feet (90 m) before impact, landing hard on the ballast and knocking himself unconscious.

[11] As the crews of the parked freight trains ran to the scene, they quickly extinguished a small fire, caused when the hot coals from the firebox of Jones' engine lit the scattered hay from one of the boxcars ablaze.

The railroad employees carried Jones' remains over half a mile to the Vaughan depot, and laid them upon a baggage cart.

The depot was closed for the night, requiring some of the men to kick the door down, in order to access the telegraph office to report the crash.

– Fireman and Messenger Injured – Passenger Train Crashed Into a Local Freight Partly on the Siding – Several Cars Demolished.

1 was running under a full head of steam when it crashed into the rear end of a caboose and three freight cars which were standing on the main track, the other portion of the train being on a sidetrack.

The caboose and two of the cars were smashed to pieces, the engine left the rails and plowed into an embankment, where it overturned and was completely wrecked, the baggage and mail coaches also being thrown from the track and badly damaged.

I imagine that the Vaughan wreck will be talked about in roundhouses, lunchrooms and cabooses for the next six months, not alone on the Illinois Central, but many other roads in Mississippi and Louisiana.

In the report, Fireman Sim Webb states that he heard the torpedo explode before going to the gangway on the engineer's side and seeing the flagman with the red and white lights standing alongside the tracks.

have disputed the official account over the years, finding it difficult if not impossible to believe that an engineer of Jones's experience would have ignored a flagman and fusees (flares) and torpedoes exploded on the rail to alert him to danger.

"[7] For at least ten years after the wreck, the imprint of Jones's engine was clearly visible in the embankment on the east side of the tracks about two-tenths of a mile north of Tucker's Creek, which is where the marker was located.

The imprint of the headlight, boiler, and the spokes of the wheels could be seen and people would ride up on handcars to view the traces of the famous wreck.

[13] The wrecked 382 was brought to the Water Valley shop and rebuilt "just as it had come from the Rogers Locomotive Works in 1898," according to Bruce Gurner.

Jones's wife received $3,000 in insurance payments (Jones was a member of two unions, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers, and had a $1,500 policy with each union), and later settled with IC for an additional $2,650 (Earl Brewer, a Water Valley attorney who would later serve as Governor of Mississippi, represented her in the settlement).

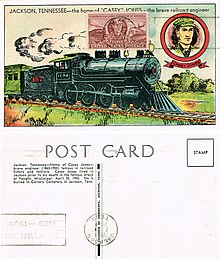

[7] Jones's tombstone in Jackson's Mount Calvary Cemetery gives his birth year as 1864, but according to information his mother wrote in the family Bible, he was born in 1863.

IWW activist Joe Hill wrote and sang a protest song parody of "The Ballad of Casey Jones", entitled ″Casey Jones—the Union Scab″.

The rebellious musicians form a local union and throw Casey down into Hell, where Satan urges him to shovel sulphur in the furnaces.

Hill's version of the song was later performed and recorded by Utah Phillips, Pete Seeger, in Russian by Leonid Utyosov, and Hungarian by the Szirt Együttes.