Catawba people

These were primarily the tribes of different language families: the Iroquois, who ranged south from the Great Lakes area and New York; the Algonquian Shawnee and Lenape (Delaware); and the Iroquoian Cherokee, who fought for control over the large Ohio Valley (including what is in present-day West Virginia).

Decimated by colonial smallpox epidemics, warfare and cultural disruption, the Catawba declined markedly in number in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Terminated as a tribe by the federal government in 1959, the Catawba Indian Nation had to reorganize to reassert their sovereignty and treaty rights.

[7] In the late 19th century, the ethnographer Henry Rowe Schoolcraft theorized that the Catawba had lived in Canada until driven out by the Iroquois (supposedly with French help) and that they had migrated to Kentucky and to Botetourt County, Virginia.

[8] However, early 20th-century anthropologist James Mooney later dismissed most elements of Schoolcraft's account as "absurd, the invention and surmise of the would-be historian who records the tradition."

Mooney accepted the tradition that, following a protracted struggle, the Catawba and Cherokee had settled on the Broad River their mutual boundary.

[8] The Catawba also had armed confrontations with several northern tribes, particularly the Haudenosaunee Seneca nation, and the Algonquian-speaking Lenape, with whom they competed for hunting resources and territory.

The governments had not been able to prevent settlers going into Iroquois territory, but the governor of Virginia offered the tribe payment for their land claim.

The peace was probably final for the Iroquois, who had established the Ohio Valley as their preferred hunting ground by right of conquest and pushed other tribes out of it.

[citation needed] In 1826, the Catawba leased nearly half their reservation to whites for a few thousand dollars of annuity; their dwindling number of members (as few as 110 by an 1896 estimate)[13] depended on this money for survival.

In 1840, by the Treaty of Nation Ford with South Carolina, the Catawba sold to the state all but one square mile (2.6 km2) of their 144,000 acres (225 sq mi; 580 km2) reserved by the English Crown.

The treaty was invalid ab initio because the state did not have the right to make it, which was reserved for the federal government, and never gained Senate ratification.

[14] About the same time, a number of the Catawba, dissatisfied with their condition among the whites, removed to join the remaining eastern Cherokee, who were based in far Western North Carolina.

[citation needed] The customs and beliefs of the early Catawba were documented by the anthropologist Frank Speck in the twentieth century.

In response, the Catawba prepared to file 60,000 lawsuits against individual landowners in York County to regain ownership of their land.

[19] On October 27, 1993, the U.S. Congress enacted the Catawba Indian Tribe of South Carolina Land Claims Settlement Act of 1993 (Settlement Act), which reversed the "termination", recognized the Catawba Indian Nation and, together with the state of South Carolina, settled the land claims for $50 million, to be applied toward economic development for the Nation.

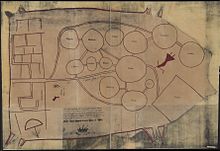

[citation needed] The Catawba Reservation (34°54′17″N 80°53′01″W / 34.90472°N 80.88361°W / 34.90472; -80.88361) is located in two disjointed sections in York County, South Carolina, east of Rock Hill.

It also has a congressionally established service area in North Carolina, covering Mecklenburg, Cabarrus, Gaston, Union, Cleveland, and Rutherford counties.

The Catawba also own a 16.57-acre (6.71 ha) site in Kings Mountain, North Carolina, which they will develop for a gaming casino and mixed-use entertainment complex.

Instead, the Catawba agreed to be governed by the terms of the Settlement Agreement and the State Act as pertains to games of chance; which at the time allowed for video poker and bingo.

[23] After the state established the South Carolina Education Lottery in 2002, the tribe lost gambling revenue and decided to shut down the Rock Hill bingo operation.

The Catawba filed suit against the state of South Carolina for the right to operate video poker and similar "electronic play" devices on their reservation.

[26] In 2014, the Catawba made a second attempt to operate a bingo parlor, opening one at what was formerly a BI-LO, on Cherry Road in Rock Hill.

[27] On September 9, 2013, the Catawba announced plans to build a $600 million casino along Interstate 85 in Kings Mountain, North Carolina.

But Governor Pat McCrory, over 100 North Carolina General Assembly members and the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) opposed it.

AS is customary, the suit names the DOI, the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs, Secretary David Bernhardt, and several other department officials.

In May 2020, the EBCI filed an amended complaint in its federal lawsuit, saying that the DOI's approval of the trust land resulted from a scheme by casino developer Wallace Cheves.

He was said to have persuaded the Catawba to lend their name to the scheme, and had a history of criminal and civil enforcement actions against him and his companies for illegal gambling.

The Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma also filed an amended complaint, seeking to protect cultural artifacts on their ancestral land where the casino is planned.

[36] On April 16, the Catawba Nation received a victory in federal court, as U.S. District Judge James Boasberg found no basis for the Cherokees' claims in the lawsuit.