Catherine de' Medici's patronage of the arts

Works of art included tapestries, hand-drawn maps, sculptures, and hundreds of pictures, many by Côme Dumoûtier and Benjamin Foulon, Catherine's last official painters.

[3] Despite the destruction, loss, and fragmentation of Catherine's heritage, a collection of portraits formerly in her possession has been assembled at the Musée Condé, Château de Chantilly.

The vogue for portrait drawings intensified during Catherine de' Medici's life, and she may have regarded part of her collection as the equivalent of today's family photograph album.

[7] On 3 July 1571, Catherine wrote to Monsieur de la Mothe-Fénelon, ambassador in London, discussing the work of François Clouet and requesting a portrait of Queen Elizabeth.

Jean drew and painted in the style of the Italian High Renaissance, but in the portraits of François, a northern-European naturalism is apparent, and a flatter, more meticulous technique.

[13] After the death of Catherine de' Medici, a decline in the quality of portraiture set in; and by 1610, the native school patronised by the late Valois court and brought to its pinnacle by François Clouet had all but died out, and the Bourbon became reliant on foreign artists.

[16] He adopted from Niccolò dell'Abbate the technique of elongated and twisted figures, placing them in spaces dominated by fantastical fragments of architecture borrowed from the drawings of Jacques Androuet du Cerceau and painted in surprising rainbow contrasts.

His most important surviving work is The Last Judgement in the Louvre, which like Caron's art, depicts human beings dwarfed by the landscape and, in Blunt's words, "made to swarm over the earth like worms".

[28] In the 1580s, Pilon began work on statues for the chapels that were to circle the tomb of Catherine de' Medici and Henry II at the basilica of Saint Denis.

"As the daughter of the Medici", suggests French art historian Jean-Pierre Babelon, "she was driven by a passion to build and a desire to leave great achievements behind her when she died.

"[32] Having witnessed in her youth the huge architectural schemes of Francis I at Chambord and Fontainebleau, Catherine set out, after Henry II's death, to enhance the grandeur of the Valois monarchy through a series of costly building projects.

In a long poem of 1562, Nicolas Houël, laying stress on her love for architecture, likened Catherine to Artemisia, who had built the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, as a tomb for her dead husband.

[40] Art historian Henri Zerner has called the design "a grand ritualistic drama which would have filled the rotunda's celestial space" and "the last and most brilliant of the royal tombs of the Renaissance".

[42] Catherine de' Medici spent extravagant sums on the building and embellishment of monuments and palaces, and as the country slipped deeper into anarchy, her plans grew ever more ambitious.

Little remains of Catherine de' Medici's investment today: one Doric column, a few fragments in the corner of the Tuileries gardens, an empty tomb at Saint Denis.

Catherine believed in the humanist ideal of the learned Renaissance prince whose power depended on letters as well as arms, and she was familiar with the writing of Erasmus, among others, on the subject.

Catherine de' Medici was also interested in Italian literature: Tasso presented his Rinaldo to her, and Aretino eulogised her as "woman and goddess serene and pure, the majesty of beings human and divine".

She drew the line at obscenity, however: in 1567, after seeing Le Brave, an adaptation of Plautus's Miles Gloriosus by one of her official poets Jean-Antoine de Baïf, Catherine told the author to cut the "lascivious talk" of the classical writers.

[56] At the same time, she believed these elaborate entertainments and sumptuous court rituals, which incorporated martial sports and tournaments of many kinds, would occupy her feuding nobles and distract them from fighting against each other to the detriment of the country and the royal authority.

[55] Catherine employed the leading writers, artists, and architects of the day, including Antoine Caron, Germain Pilon, and Pierre Ronsard, to create the dramas, music, scenic effects, and decorative works required to animate the themes of the festivals, which were usually mythological and dedicated to the ideal of peace in the realm.

It is difficult for scholars to reconstruct the exact form of Catherine's entertainments, but research into the written accounts, scripts, artworks, and tapestries that derived from these famous occasions has provided evidence of their richness and scale.

She forbade heavy tilting of the sort that led to the death of her husband in 1559; and she developed and increased the prominence of dance in the shows that climaxed each series of entertainments.

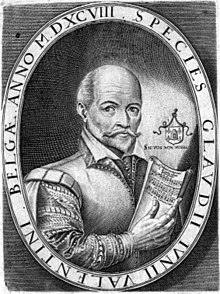

[61] The most significant figure was Balthasar de Beaujoyeulx (his name gallicised from the Italian Baldassare da Belgiojoso), whom Catherine placed in charge of training dancers and producing performances at court.

[62] Historian Frances Yates has credited Catherine as the guiding light of the ballets de cour: It was invented in the context of the chivalrous pastimes of the court, by an Italian, and a Medici, the Queen Mother.

Many poets, artists, musicians, choreographers, contributed to the result, but it was she who was the inventor, one might perhaps say, the producer; she who had the ladies of her court trained to perform these ballets in settings of her devising.

Choreographed by Beaujoyeulx, the dancers performed complex, interlaced figures and patterned movements, each expressing a certain moral or spiritual truth that the spectators, assisted by printed programmes, were expected to recognise.

[67] The figured choreography that enacted the mythological and symbolic themes reflected the principle, derived from the Enneads of Plotinus (c. 205–270), of "cosmic dance", the imitation of heavenly bodies by human motion to produce harmony.

[64] The Ballet Comique de la Reine marked the final transformation of court dance as a purely personal and social activity into a unified theatrical performance with a philosophical and political agenda.

[70] The dance, verse, and musical elements of Catherine's entertainments increasingly reflected the principles of an academic movement—also influential in the Florentine Camerata—to unify the performing arts in what was believed to be the classical, Greek way.

[73] When, at the climax of the show, Jupiter descended from the heavens, forty singers and musicians performed a song in honour of the wisdom and virtue of the Valois monarchy.