Catholic art

The Protestant Reformation in the 16th century produced new waves of image-destruction, to which the Catholic Church responded with the dramatic, elaborate emotive Baroque and Rococo styles to emphasise beauty as a transcendental.

These basilica-churches had a center nave with one or more aisles at each side and a rounded apse at one end: on this raised platform sat the bishop and priests, and also the altar.

Richer materials could now be used for art, such as the mosaics that decorate Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome and the 5th century basilicas of Ravenna, where narrative sequences begin to develop.

The dedication of Constantinople as capital in 330 AD created a great new Christian artistic centre for the Eastern Roman Empire, which soon became a separate political unit.

Byzantine art became increasingly conservative, as the form of images themselves, many accorded divine origin or thought to have been painted by Saint Luke or other figures, was held to have a status not far off that of a scriptural text.

Other images that are certainly of Greek origin, like the Salus Populi Romani and Our Lady of Perpetual Help, both icons in Rome, have been subjects of specific veneration for centuries.

El Greco left Crete when relatively young, but Michael Damaskinos returned after a brief period in Venice, and was able to switch between Italian and Greek styles.

It was prepared circa 790 for Charlemagne after a bad translation had led his court to believe that the Byzantine Second Council of Nicaea had approved the worship of images, which in fact was not the case.

Bernard was in fact only opposed to decorative imagery in monasteries that was not specifically religious, and popular preachers like Saint Bernardino of Siena and Savonarola regularly targeted secular images owned by the laity.

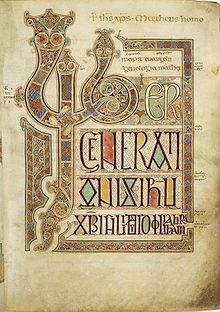

[5] Anglo-Saxon art was often freer, making more use of lively line drawings, and there were other distinct traditions, such as the group of extraordinary Mozarabic manuscripts from Spain, including the Saint-Sever Beatus, and those in Girona and the Morgan Library.

Charlemagne had a life-size crucifix with the figure of Christ in precious metal in his Palatine Chapel in Aachen, and many such objects, all now vanished, are recorded in large Anglo-Saxon churches and elsewhere.

Carvings in stone adorned the exteriors and interiors, particularly the tympanum above the main entrance, which often featured a Christ in Majesty or in Judgement, and the large wooden crucifix was a German innovation right at the start of the period.

The principal media of Gothic art were sculpture, panel painting, stained glass, fresco and the illuminated manuscript, though religious imagery was also expressed in metalwork, tapestries and embroidered vestments.

Artists like Giotto, Fra Angelico and Pietro Lorenzetti in Italy, and Early Netherlandish painting, brought realism and a more natural humanity to art.

Iconography was affected by changes in theology, with depictions of the Assumption of Mary gaining ground on the older Death of the Virgin, and in devotional practices such as the Devotio Moderna, which produced new treatments of Christ in andachtsbilder subjects such as the Man of Sorrows, Pensive Christ and Pietà, which emphasized his human suffering and vulnerability, in a parallel movement to that in depictions of the Virgin.

Over the period many ancient iconographical features that originated in New Testament apocrypha were gradually eliminated under clerical pressure, like the midwives at the Nativity, though others were too well-established, and considered harmless.

By the end of the century, printed books with illustrations, still mostly on religious subjects, were rapidly becoming accessible to the prosperous middle class, as were engravings of fairly high-quality by printmakers like Israhel van Meckenem and Master E. S. For the wealthy, small panel paintings, even polyptychs in oil painting, were becoming increasingly popular, often showing donor portraits alongside, though often much smaller than, the Virgin or saints depicted.

However a clear loss of religious intensity is apparent in many Early Renaissance religious paintings – the famous frescoes in the Tornabuoni Chapel by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1485–1490) seem more interested in the detailed depiction of scenes of bourgeois city life than their actual subjects, the Life of the Virgin and that of John the Baptist, and the Magi Chapel of Benozzo Gozzoli (1459–1461) is more a celebration of Medici status than an Arrival of the Magi.

Some stone sculpture, illuminated manuscripts and stained glass windows (expensive to replace) survived, but of the thousands of high quality works of painted and wood-carved art produced in medieval Britain, virtually none remain.

[10] In Rome, the sack of 1527 by the Catholic Emperor Charles V and his largely Protestant mercenary troops was enormously destructive both of art and artists, many of whose biographical records end abruptly.

Italian painting after 1520, with the notable exception of the art of Venice, developed into Mannerism, a highly sophisticated style, striving for effect, that drew the concern of many churchman that it lacked appeal for the mass of the population.

Previous Catholic Church councils had rarely felt the need to pronounce on these matters, unlike Orthodox ones which have often ruled on specific types of images.

[13] But the number of such decorative treatments of religious subjects declined sharply, as did "unbecomingly or confusedly arranged" Mannerist pieces, as a number of books, notably by the Flemish theologian Molanus (De Picturis et Imaginibus Sacris, pro vero earum usu contra abusus ("Treatise on Sacred Images"), 1570), Cardinal Federico Borromeo (De Pictura Sacra) and Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti (Discorso, 1582), and instructions by local bishops, amplified the decrees, often going into minute detail on what was acceptable.

One of the earliest of these, Degli Errori dei Pittori (1564), by the Dominican theologian Andrea Gilio da Fabriano, joined the chorus of criticism of Michelangelo's Last Judgement and defended the devout and simple nature of much medieval imagery.

New iconic subjects popularized in the Baroque period included the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and the Immaculate Conception of Mary; the definitive iconography for the latter seems to have been established by the master and then father-in-law of Diego Velázquez, the painter and theorist Francisco Pacheco, to whom the Inquisition in Seville also contracted the approval of new images.

After a spate of building and re-building in the Baroque period, Catholic countries were mostly clearly overstocked with churches, monasteries and convents, in the case of some places such as Naples, almost absurdly so.

The number of sales of paintings, metalwork and other church fittings to private collectors increased during the century, especially in Italy, where the Grand Tour gave rise to networks of dealers and agents.

Suppression of monasteries, which had been under way for decades under Catholic Enlightened despots of the Ancien Régime, for example in the Edict on Idle Institutions (1780) of Joseph II of Austria, intensified considerably.

This undoubtedly widened access to many works, and promoted public awareness of the heritage of Catholic art, but at a cost, as objects came to be regarded as of primarily artistic rather than religious significance, and were seen out of their original context and the setting they were designed for.

Architects began to revive other earlier Christian styles, and experiment with new ones, producing results such as Sacre Coeur in Paris, Sagrada Familia in Barcelona and the Byzantine-influenced Westminster Cathedral in London.