Causal graph

In statistics, econometrics, epidemiology, genetics and related disciplines, causal graphs (also known as path diagrams, causal Bayesian networks or DAGs) are probabilistic graphical models used to encode assumptions about the data-generating process.

As communication devices, the graphs provide formal and transparent representation of the causal assumptions that researchers may wish to convey and defend.

As inference tools, the graphs enable researchers to estimate effect sizes from non-experimental data,[1][2][3][4][5] derive testable implications of the assumptions encoded,[1][6][7][8] test for external validity,[9] and manage missing data[10] and selection bias.

[11] Causal graphs were first used by the geneticist Sewall Wright[12] under the rubric "path diagrams".

They were later adopted by social scientists[13][14][15][16][17] and, to a lesser extent, by economists.

[18] These models were initially confined to linear equations with fixed parameters.

Modern developments have extended graphical models to non-parametric analysis, and thus achieved a generality and flexibility that has transformed causal analysis in computer science, epidemiology,[19] and social science.

Causal models often include "error terms" or "omitted factors" which represent all unmeasured factors that influence a variable Y when Pa(Y) are held constant.

However, if the graph author suspects that the error terms of any two variables are dependent (e.g. the two variables have an unobserved or latent common cause) then a bidirected arc is drawn between them.

Thus, the presence of latent variables is taken into account through the correlations they induce between the error terms, as represented by bidirected arcs.

A fundamental tool in graphical analysis is d-separation, which allows researchers to determine, by inspection, whether the causal structure implies that two sets of variables are independent given a third set.

In recursive models without correlated error terms (sometimes called Markovian), these conditional independences represent all of the model's testable implications.

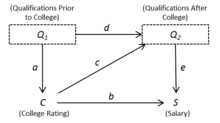

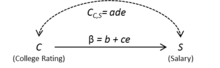

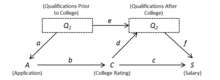

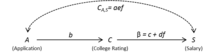

[22] Suppose we wish to estimate the effect of attending an elite college on future earnings.

Simply regressing earnings on college rating will not give an unbiased estimate of the target effect because elite colleges are highly selective, and students attending them are likely to have qualifications for high-earning jobs prior to attending the school.

Assuming that the causal relationships are linear, this background knowledge can be expressed in the following structural equation model (SEM) specification.

Figure 1 is a causal graph that represents this model specification.

In some cases, we may label the arrow with its corresponding structural coefficient as in Figure 1.

This can be verified using the single-door criterion,[1][23] a necessary and sufficient graphical condition for the identification of a structural coefficients, like