Causes of the euro area crisis

The European sovereign debt crisis resulted from the structural problem of the eurozone and a combination of complex factors, including the globalisation of finance; easy credit conditions during the 2002–2008 period that encouraged high-risk lending and borrowing practices; the 2008 financial crisis; international trade imbalances; real-estate bubbles that have since burst; the 2008–2012 global recession; fiscal policy choices related to government revenues and expenses; and approaches used by nations to bail out troubled banking industries and private bondholders, assuming private debt burdens or socialising losses.

In Greece, the government increased its commitments to public workers in the form of extremely generous wage and pension benefits, with the former doubling in real terms over 10 years.

Should Italy be unable to finance itself, the French banking system and economy could come under significant pressure, which in turn would affect France's creditors and so on.

[8] Greece, Italy and other countries tried to artificially reduce their budget deficits deceiving EU officials with the help of derivatives designed by major banks.

In 1992, members of the European Union signed the Maastricht Treaty, under which they pledged to limit their deficit spending and debt levels.

[16] This allowed the sovereigns to mask their deficit and debt levels through a combination of techniques, including inconsistent accounting, off-balance-sheet transactions[16] as well as the use of complex currency and credit derivatives structures.

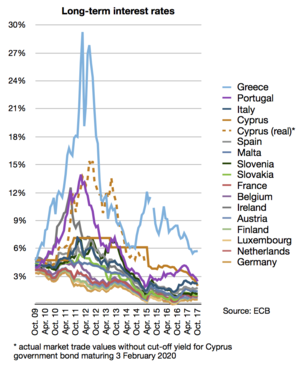

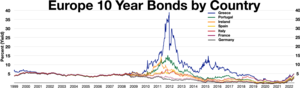

"[4] As a result, creditors in countries with originally weak currencies (and higher interest rates) suddenly enjoyed much more favorable credit terms, which spurred private and government spending and led to an economic boom.

In some countries, such as Ireland and Spain, low interest rates also led to a housing bubble, which burst at the height of the financial crisis.

[23] British economic historian Robert Skidelsky added that it was indeed excessive lending by banks, not deficit spending that created this crisis.

He notes in the run-up to the crisis, from 1999 to 2007, Germany had a considerably better public debt and fiscal deficit relative to GDP than the most affected eurozone members.

But bubbles always burst sooner or later, and yesterday’s miracle economies have become today’s basket cases, nations whose assets have evaporated but whose debts remain all too real.

Instead the opposite happened: the gap between German and Greek productivity increased, resulting in a large current account surplus financed by capital flows.

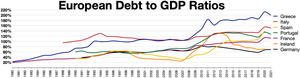

[37] Economic evidence indicates the crisis may have more to do with trade deficits (which require private borrowing to fund) than public debt levels.

"[38] A February 2013 paper from four economists concluded that, "Countries with debt above 80 % of GDP and persistent current-account [trade] deficits are vulnerable to a rapid fiscal deterioration..."[39][40][41] One theory is that these problems are caused by a structural contradiction within the euro system, the theory is that there is a monetary union (common currency) without a fiscal union (e.g., common taxation, pension, and treasury functions).

This feature brought fiscal free riding of peripheral economies, especially represented by Greece, as it is hard to control and regulate national financial institutions.

When countries with such different cultures become this interconnected and interdependent – when they share the same currency but not the same work ethics, retirement ages or budget discipline – you end up with German savers seething at Greek workers, and vice versa.

Contributing to lack of information about the risk of European sovereign debt was conflict of interest by banks that were earning substantial sums underwriting the bonds.

According to The Economist, the crisis "is as much political as economic" and the result of the fact that the euro area is not supported by the institutional paraphernalia (and mutual bonds of solidarity) of a state.

[57] Portfolio data and repeated surveys of an Italian bank's clients have shown that investors' risk aversion substantially increased after the 2008 crisis.

[58] From a macroeconomic perspective, risk aversion was an important mechanism underlying financial decisions, output, and real money balance dynamics during the European debt crisis.

[60] On 5 December 2011, S&P placed its long-term sovereign ratings on 15 members of the eurozone on "CreditWatch" with negative implications; S&P wrote that this was due to "systemic stresses from five interrelated factors: