Celts

The interrelationships of ethnicity, language and culture in the Celtic world are unclear and debated;[8] for example over the ways in which the Iron Age people of Britain and Ireland should be called Celts.

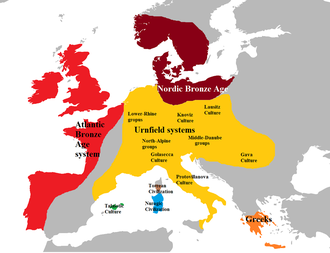

The traditional "Celtic from the East" theory, says the proto-Celtic language arose in the late Bronze Age Urnfield culture of central Europe, named after grave sites in southern Germany,[12][13] which flourished from around 1200 BC.

[16] A newer theory, "Celtic from the West", suggests proto-Celtic arose earlier, was a lingua franca in the Atlantic Bronze Age coastal zone, and spread eastward.

He suggests it meant the people or descendants of "the hidden one", noting the Gauls claimed descent from an underworld god (according to Commentarii de Bello Gallico), and linking it with the Germanic Hel.

He says "If the Gauls' initial impact on the Mediterranean world was primarily a military one typically involving fierce young *galatīs, it would have been natural for the Greeks to apply this name for the type of Keltoi that they usually encountered".

After the word 'Celtic' was rediscovered in classical texts, it was applied for the first time to the distinctive culture, history, traditions, and language of the modern Celtic nations – Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, Brittany, and the Isle of Man.

[37] 'Celt' is a modern English word, first attested in 1707 in the writing of Edward Lhuyd, whose work, along with that of other late 17th-century scholars, brought academic attention to the languages and history of the early Celtic inhabitants of Great Britain.

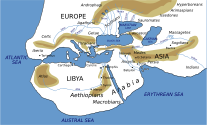

By the time Celts are first mentioned in written records around 400 BC, they were already split into several language groups, and spread over much of western mainland Europe, the Iberian Peninsula, Ireland and Britain.

[46][47] The mainstream view during most of the twentieth century is that the Celts and the proto-Celtic language arose out of the Urnfield culture of central Europe around 1000 BC, spreading westward and southward over the following few hundred years.

However, Stephen Oppenheimer shows that Herodotus seemed to believe the Danube rose near the Pyrenees, which would place the Ancient Celts in a region which is more in agreement with later classical writers and historians (i.e. in Gaul and Iberia).

[11] A new theory suggested that Celtic languages arose earlier, along the Atlantic coast (including Britain, Ireland, Armorica and Iberia), long before evidence of 'Celtic' culture is found in archaeology.

Myles Dillon and Nora Kershaw Chadwick argued that "Celtic settlement of the British Isles" might date to the Bell Beaker culture of the Copper and Bronze Age (from c. 2750 BC).

[60] Arnaiz-Villena et al. (2017) demonstrated that Celtic-related populations of the European Atlantic (Orkney Islands, Scottish, Irish, British, Bretons, Basques, Galicians) shared a common HLA system.

At the beginning of the 20th century the belief that these "Culture Groups" could be thought of in racial or ethnic terms was held by Gordon Childe, whose theory was influenced by the writings of Gustaf Kossinna.

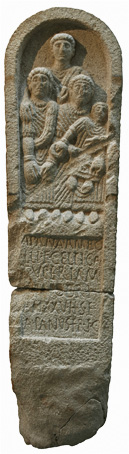

Frey notes that in the 5th century, "burial customs in the Celtic world were not uniform; rather, localised groups had their own beliefs, which, in consequence, also gave rise to distinct artistic expressions".

[citation needed] The Greek historian Ephorus of Cyme in Asia Minor, writing in the 4th century BC, believed the Celts came from the islands off the mouth of the Rhine and were "driven from their homes by the frequency of wars and the violent rising of the sea".

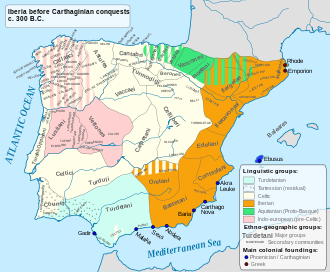

[84] A modern scholarly review[85] found several archaeological groups of Celts in Spain: The origins of the Celtiberians might provide a key to understanding the Celticisation process in the rest of the Peninsula.

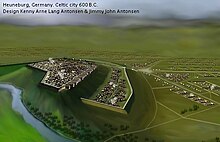

Some, like the Heuneburg, the oldest city north of the Alps,[97] grew to become important cultural centres of the Iron Age in Central Europe, that maintained trade routes to the Mediterranean.

The older view was that Celtic influence in the Isles was the result of successive migrations or invasions from the European mainland by diverse Celtic-speaking peoples over several centuries, accounting for the P-Celtic vs. Q-Celtic isogloss.

By the 10th century AD, the Insular Celtic peoples had diversified into the Brittonic-speaking Welsh (in Wales), Cornish (in Cornwall), Bretons (in Brittany) and Cumbrians (in the Old North); and the Gaelic-speaking Irish (in Ireland), Scots (in Scotland) and Manx (on the Isle of Man).

In historical times, the offices of high and low kings in Ireland and Scotland were filled by election under the system of tanistry, which eventually came into conflict with the feudal principle of primogeniture in which succession goes to the first-born son.

The horned Waterloo Helmet in the British Museum, which long set the standard for modern images of Celtic warriors, is in fact a unique survival; it may have been a piece for ceremonial rather than military wear.

Low-value coinages of potin, a bronze alloy with high tin content, were minted in most Celtic areas of the continent and in South-East Britain prior to the Roman conquest of these lands.

[161] Cassius Dio suggests there was great sexual freedom among women in Celtic Britain:[162] ... a very witty remark is reported to have been made by the wife of Argentocoxus, a Caledonian, to Julia Augusta.

[167] Under Brehon Law, which was written down in early Medieval Ireland after conversion to Christianity, a woman had the right to divorce her husband and gain his property if he was unable to perform his marital duties due to impotence, obesity, homosexual inclination or preference for other women.

Much of the surviving material is in precious metal, which no doubt gives a very unrepresentative picture, but apart from Pictish stones and the Insular high crosses, large monumental sculpture, even with decorative carving, is very rare; possibly it was originally common in wood.

[citation needed] French archaeologist J. Monard speculated that it was recorded by druids wishing to preserve their tradition of timekeeping in a time when the Julian calendar was imposed throughout the Roman Empire.

"[182] Writing in the first century BC, Greek historians Posidonius and Diodorus Siculus said Celtic warriors cut off the heads of enemies slain in battle, hung them from the necks of their horses, then nailed them up outside their homes.

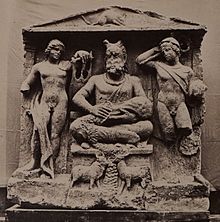

[193] Some figures in medieval Insular Celtic myth have ancient continental parallels: Irish Lugh and Welsh Lleu are cognate with Lugus, Goibniu and Gofannon with Gobannos, Macán and Mabon with Maponos, while Macha and Rhiannon may be counterparts of Epona.

Some mythical heroes visit it by entering ancient burial mounds or caves, by going under water or across the western sea, or after being offered a silver apple branch by an Otherworld resident.

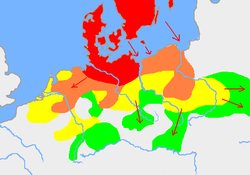

-

Core Hallstatt territory, by the sixth century BC

-

Greatest Celtic expansion by 275 BC

-

Lusitanian area of Iberia where Celtic presence is uncertain

-

Areas in which Celtic languages were spoken throughout the Middle Ages

-

Areas where Celtic languages remain widely spoken today