Western Allied invasion of Germany

[16][l][18] Combined with the capture of Berchtesgaden, any hope of Nazi leadership continuing to wage war from a so-called "national redoubt" or escape through the Alps was crushed, shortly followed by unconditional German surrender on 8 May 1945.

With the Soviets at the door of Berlin, the western Allies decided any attempt on their behalf to push that far east would be too costly, concentrating instead on mopping up resistance in the west German cities.

According to rumor, Hitler's most fanatically loyal troops were preparing to make a lengthy, last-ditch stand in the natural fortresses formed by the rugged alpine mountains of southern Germany and western Austria.

In reality, by the time of the Allied Rhine crossings the Wehrmacht had suffered such severe defeats on both the Eastern and Western Fronts that it could barely manage to mount effective delaying actions, much less muster enough troops to establish a well-organized alpine resistance force.

While Montgomery was carefully and cautiously planning for the main thrust in the north, complete with massive artillery preparation and an airborne assault, American forces in the south were displaying the kind of basic aggressiveness that Eisenhower wanted to see.

Although Montgomery's drive was still planned as the main effort, Eisenhower believed that the momentum of the American forces to the south should not be squandered by having them merely hold the line at the Rhine or make only limited diversionary attacks beyond it.

At first, this was done informally with occupants evicted immediately and taking with them few personal possessions, but the process became standardized, with three hours' notice and OMGUS personnel providing receipts for buildings' contents.

[28] These were exactly the orders Patton had hoped for; he felt that if a sufficiently strong force could be thrown across the river and significant gains made, then Eisenhower might transfer responsibility for the main drive through Germany from Montgomery's 21st Army Group to Bradley's 12th.

As soon as Patton had received the orders on the 19th to make a crossing, he had begun sending assault boats, bridging equipment and other supplies forward from depots in Lorraine where they had been stockpiled since autumn in the expectation of just such an opportunity.

In a departure from standard airborne doctrine, which called for a jump deep behind enemy lines several hours prior to an amphibious assault, Varsity's drop zones were close behind the German front, within Allied artillery range.

The wisdom of putting lightly armed paratroopers so close to the main battlefield was debated, and the plan for amphibious forces to cross the Rhine prior to the parachute drop raised questions as to the utility of making an airborne assault at all.

An intense exchange of fire lasted for about thirty minutes as assault boats kept pushing across the river and those men who had already made it across mounted attacks against the scattered defensive strongpoints.

VIII Corps crossing sites were located along the Rhine Gorge, where the river had carved a deep chasm between two mountain ranges, creating precipitous canyon walls over 300 feet (91 m) high on both sides.

[30] Plunder began on the evening of 23 March with the assault elements of the British 2nd Army massed against three main crossing sites: Rees in the north, Xanten in the center, and Wesel in the south.

When limited objective attacks provoked little response on the morning of the 25th, the division commander Major General Leland Hobbs formed two mobile task forces to make deeper thrusts with an eye toward punching through the defense altogether and breaking deep into the German rear.

The next day they gained some more ground, and one even seized its objective, having slogged a total of 6 miles (9.7 km), but the limited progress forced Hobbs to abandon the hope for a quick breakout.

The only potent unit left for commitment against the Allied Rhine crossings in the north, the 116th began moving south from the Dutch-German border on 25 March against what the Germans considered their most dangerous threat, the U.S. 9th Army.

Also on 28 March, elements of the U.S. 17th Airborne Division operating north of the Lippe River in conjunction with British armored forces—dashed to a point some 30 mi (48 km) east of Wesel, opening a corridor for the XIX Corps and handily outflanking Dorsten and the enemy to the south.

After passing north of the Lippe on 29 March, the 2nd Armored Division broke out late that night from the forward position that the XVIII Airborne Corps had established around Haltern, 12 mi (19 km) northeast of Dorsten.

German Field Marshal Walter Model, whose Army Group B was charged with the defense of the Ruhr, had deployed his troops heavily along the east–west Sieg River south of Cologne, thinking that the Americans would attack directly north from the Remagen bridgehead.

The U.S. VII Corps, on the left, had the hardest going due to the German concentration north of the bridgehead, yet its armored columns managed to advance 12 mi (19 km) beyond their line of departure.

[38] Beginning the next day, 26 March, the armored divisions of all three corps turned these initial gains into a complete breakout, shattering all opposition and roaming at will throughout the enemy's rear areas.

By the end of 28 March, Hodges' 1st Army had crossed the Lahn, having driven at least 50 mi (80 km) beyond the original line of departure, capturing thousands of German soldiers in the process.

When the task force failed to advance on 31 March, Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins, commander of the VII Corps, asked Simpson if his 9th Army, driving eastward north of the Ruhr, could provide assistance.

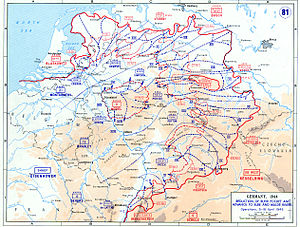

With spectacular thrusts being made beyond the Rhine nearly every day and the enemy's capacity to resist fading at an ever-accelerating rate, the campaign to finish Germany was transitioning into a general pursuit.

At the same time, General Devers' 6th U.S. Army Group would move south through Bavaria and the Black Forest to Austria and the Alps, ending the threat of any Nazi last-ditch stand there.

The change resulted from an agreement between the American and Soviet military leadership based on the need to establish a readily identifiable geographical line to avoid accidental clashes between the converging Allied forces.

Britain's Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, urged Eisenhower to continue the advance toward Berlin by the 21st Army Group, under the command of Montgomery with the intention of capturing the city.

[58] After Bradley warned that capturing a city located in a region that the Soviets had already received at the Yalta Conference might cost 100,000 casualties,[58] by 15 April Eisenhower ordered all armies to halt when they reached the Elbe and Mulde Rivers, thus immobilizing these spearheads while the war continued for three more weeks.

With his escape route to the south severed by the 12th Army Group's eastward drive and Berlin surrounded by the Soviets, Hitler committed suicide on 30 April, leaving to his successor, Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, the task of capitulation.