Cephalopod

A cephalopod /ˈsɛfələpɒd/ is any member of the molluscan class Cephalopoda /sɛfəˈlɒpədə/ (Greek plural κεφαλόποδες, kephalópodes; "head-feet")[3] such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus.

These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral body symmetry, a prominent head, and a set of arms or tentacles (muscular hydrostats) modified from the primitive molluscan foot.

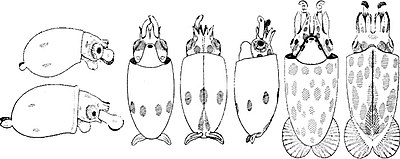

The class now contains two, only distantly related, extant subclasses: Coleoidea, which includes octopuses, squid, and cuttlefish; and Nautiloidea, represented by Nautilus and Allonautilus.

[9] Cephalopods are thought to be unable to live in fresh water due to multiple biochemical constraints, and in their >400 million year existence have never ventured into fully freshwater habitats.

The giant nerve fibers of the cephalopod mantle have been widely used for many years as experimental material in neurophysiology; their large diameter (due to lack of myelination) makes them relatively easy to study compared with other animals.

[23] Consequently, cephalopod vision is acute: training experiments have shown that the common octopus can distinguish the brightness, size, shape, and horizontal or vertical orientation of objects.

Coleoid cephalopods (octopus, squid, cuttlefish) have a single photoreceptor type and lack the ability to determine color by comparing detected photon intensity across multiple spectral channels.

The unusual off-axis slit and annular pupil shapes in cephalopods enhance this ability by acting as prisms which are scattering white light in all directions.

[41] Evidence of original coloration has been detected in cephalopod fossils dating as far back as the Silurian; these orthoconic individuals bore concentric stripes, which are thought to have served as camouflage.

[43] Coleoids, a shell-less subclass of cephalopods (squid, cuttlefish, and octopuses), have complex pigment containing cells called chromatophores which are capable of producing rapidly changing color patterns.

For example, when the octopus Callistoctopus macropus is threatened, it will turn a bright red brown color speckled with white dots as a high contrast display to startle predators.

It lies beneath the gut and opens into the anus, into which its contents – almost pure melanin – can be squirted; its proximity to the base of the funnel means the ink can be distributed by ejected water as the cephalopod uses its jet propulsion.

But unlike hemoglobin, which are attached in millions on the surface of a single red blood cell, hemocyanin molecules float freely in the bloodstream.

[69] Since the Paleozoic era, as competition with fish produced an environment where efficient motion was crucial to survival, jet propulsion has taken a back role, with fins and tentacles used to maintain a steady velocity.

That being said, squid and other cephalopod that dwell in deep waters tend to be more neutrally buoyant which removes the need to regulate depth and increases their locomotory efficiency.

[91] Females of the octopus genus Argonauta secrete a specialized paper-thin egg case in which they reside, and this is popularly regarded as a "shell", although it is not attached to the body of the animal and has a separate evolutionary origin.

[97] Externally shelled nautilids (Nautilus and Allonautilus) have on the order of 90 finger-like appendages, termed tentacles, which lack suckers but are sticky instead, and are partly retractable.

[25] Cells in the digestive gland directly release pigmented excretory chemicals into the lumen of the gut, which are then bound with mucus passed through the anus as long dark strings, ejected with the aid of exhaled water from the funnel.

Several outgrowths of the lateral vena cava project into the renal sac, continuously inflating and deflating as the branchial hearts beat.

[110] Stearns (1992) suggested that in order to produce the largest possible number of viable offspring, spawning events depend on the ecological environmental factors of the organism.

[124] Fertilized egg clusters are neutrally buoyant depending on the depth that they were laid, but can also be found in substrates such as sand, a matrix of corals, or seaweed.

[111] Because these species do not provide parental care for their offspring, egg capsules can be injected with ink by the female in order to camouflage the embryos from predators.

[129] The process from spawning to hatching follows a similar trajectory in all species, the main variable being the amount of yolk available to the young and when it is absorbed by the embryo.

[132] The traditional view of cephalopod evolution holds that they evolved in the Late Cambrian from a monoplacophoran-like ancestor[133] with a curved, tapering shell,[134] which was closely related to the gastropods (snails).

[144] In the Early Palaeozoic, their range was far more restricted than today; they were mainly constrained to sublittoral regions of shallow shelves of the low latitudes, and usually occurred in association with thrombolites.

Although the role of transposable elements in marine vertebrates is still relatively unknown, significant expression of transposons in nervous system tissues have been observed.

Shevyrev (2005) suggested a division into eight subclasses, mostly comprising the more diverse and numerous fossil forms,[164][165] although this classification has been criticized as arbitrary, lacking evidence, and based on misinterpretations of other papers.

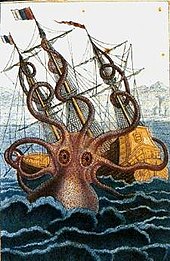

[170] Ancient seafaring people were aware of cephalopods, as evidenced by such artworks as a stone carving found in the archaeological recovery from Bronze Age Minoan Crete at Knossos (1900 – 1100 BC), which has a depiction of a fisherman carrying an octopus.

[176] A battle with an octopus plays a significant role in Victor Hugo's book Travailleurs de la mer (Toilers of the Sea), relating to his time in exile on Guernsey.

[177] Ian Fleming's 1966 short story collection Octopussy and The Living Daylights, and the 1983 James Bond film were partly inspired by Hugo's book.