Animal embryonic development

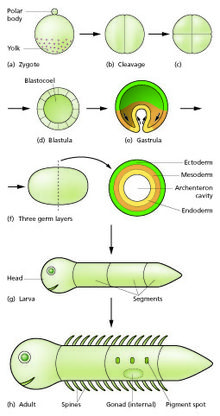

The zygote undergoes mitotic divisions with no significant growth (a process known as cleavage) and cellular differentiation, leading to development of a multicellular embryo[2] after passing through an organizational checkpoint during mid-embryogenesis.

In animals, the process involves a sperm fusing with an ovum, which eventually leads to the development of an embryo.

Fast block, the membrane potential rapidly depolarizing and then returning to normal, happens immediately after an egg is fertilized by a single sperm.

Slow block begins in the first few seconds after fertilization and is when the release of calcium causes the cortical reaction, in which various enzymes are released from cortical granules in the eggs plasma membrane, causing the expansion and hardening of the outside membrane, preventing more sperm from entering.

In the early mouse embryo, the sister cells of each division remain connected during interphase by microtubule bridges.

[8][9] Holoblastic cleavage occurs in animals with little yolk in their eggs,[10] such as humans and other mammals who receive nourishment as embryos from the mother, via the placenta or milk, such as might be secreted from a marsupium.

[citation needed] Mammals at this stage form a structure called the blastocyst,[1] characterized by an inner cell mass that is distinct from the surrounding blastula.

As already stated, the cells of the trophoblast do not contribute to the formation of the embryo proper; they form the ectoderm of the chorion and play an important part in the development of the placenta.

Towards the narrow, posterior end, an opaque primitive streak, is formed and extends along the middle of the disc for about half of its length; at the anterior end of the streak there is a knob-like thickening termed the primitive node or knot, (known as Hensen's knot in birds).

The primitive streak is produced by a thickening of the axial part of the ectoderm, the cells of which multiply, grow downward, and blend with those of the subjacent endoderm.

The blastoderm now consists of three layers, an outer ectoderm, a middle mesoderm, and an inner endoderm; each has distinctive characteristics and gives rise to certain tissues of the body.

[18][20] During gastrulation cells migrate to the interior of the blastula, subsequently forming two (in diploblastic animals) or three (triploblastic) germ layers.

The groove gradually deepens as the neural folds become elevated, and ultimately the folds meet and coalesce in the middle line and convert the groove into a closed tube, the neural tube or canal, the ectodermal wall of which forms the rudiment of the nervous system.

The coalescence of the neural folds occurs first in the region of the hind brain, and from there extends forward and backward; toward the end of the third week, the front opening (anterior neuropore) of the tube finally closes at the anterior end of the future brain, and forms a recess that is in contact, for a time, with the overlying ectoderm; the hinder part of the neural groove presents for a time a rhomboidal shape, and to this expanded portion the term sinus rhomboidalis has been applied.

[citation needed] By the upward growth of the mesoderm, the neural tube is ultimately separated from the overlying ectoderm.

[24][9] The cephalic end of the neural groove exhibits several dilatations that, when the tube is closed, assume the form of the three primary brain vesicles, and correspond, respectively, to the future forebrain (prosencephalon), midbrain (mesencephalon), and hindbrain (rhombencephalon) (Fig.

The walls of the vesicles are developed into the nervous tissue and neuroglia of the brain, and their cavities are modified to form its ventricles.

[25] Toward the end of the second week after fertilization, transverse segmentation of the paraxial mesoderm begins, and it is converted into a series of well-defined, more or less cubical masses, also known as the somites, which occupy the entire length of the trunk on either side of the middle line from the occipital region of the head.