Engraving

Engraving was a historically important method of producing images on paper in artistic printmaking, in mapmaking, and also for commercial reproductions and illustrations for books and magazines.

Engravers use a hardened steel tool called a burin, or graver, to cut the design into the surface, most traditionally a copper plate.

[3] However, modern hand engraving artists use burins or gravers to cut a variety of metals such as silver, nickel, steel, brass, gold, and titanium, in applications ranging from weaponry to jewellery to motorcycles to found objects.

The burin produces a unique and recognizable quality of line that is characterized by its steady, deliberate appearance and clean edges.

When the tool's point breaks or chips, even on a microscopic level, the graver can become hard to control and produces unexpected results.

Modern innovations have brought about new types of carbide that resist chipping and breakage, which hold a very sharp point longer between resharpening than traditional metal tools.

Very few master engravers exist today who rely solely on "feel" and muscle memory to sharpen tools.

Originally, handpieces varied little in design as the common use was to push with the handle placed firmly in the center of the palm.

With modern pneumatic engraving systems, handpieces are designed and created in a variety of shapes and power ranges.

The traditional "hand push" process is still practiced today, but modern technology has brought various mechanically assisted engraving systems.

The internal mechanisms move at speeds up to 15,000 strokes per minute, thereby greatly reducing the effort needed in traditional hand engraving.

One of the major benefits of using a pneumatic system for hand engraving is the reduction of fatigue and decrease in time spent working.

Pneumatic systems greatly reduce the effort required for removing large amounts of metal, such as in deep relief engraving or Western bright cut techniques.

A variety of spray lacquers and finishing techniques exist to seal and protect the work from exposure to the elements and time.

Finishing also may include lightly sanding the surface to remove small chips of metal called "burrs" that are very sharp and unsightly.

Some engravers prefer high contrast to the work or design, using black paints or inks to darken removed (and lower) areas of exposed metal.

The modern discipline of hand engraving, as it is called in a metalworking context, survives largely in a few specialized fields.

Engraving machines such as the K500 (packaging) or K6 (publication) by Hell Gravure Systems use a diamond stylus to cut cells.

The machine uses an electronic spindle to quickly rotate the head as it pushes it into the material, then pulls it along whilst it continues to spin.

Today laser engraving machines are in development but still mechanical cutting has proven its strength in economical terms and quality.

[4] Hatched banding upon ostrich eggshells used as water containers found in South Africa in the Diepkloof Rock Shelter and dated to the Middle Stone Age around 60,000 BC are the next documented case of human engraving.

Many classic postage stamps were engraved, although the practice is now mostly confined to particular countries, or used when a more "elegant" design is desired and a limited color range is acceptable.

In the United States, especially during the Great Depression, coin engraving on the large-faced Indian Head nickel became a way to help make ends meet.

The craft continues today, and with modern equipment often produces stunning miniature sculptural artworks and floral scrollwork.

For correction, the plate was held on a bench by callipers, hit with a dot punch on the opposite side, and burnished to remove any signs of the defective work.

The process involved intensive pre-planning of the layout, and many manuscript scores with engraver's planning marks survive from the 18th and 19th centuries.

[9]By 1837 pewter had replaced copper as a medium, and Berthiaud gives an account with an entire chapter devoted to music (Novel manuel complet de l'imprimeur en taille douce, 1837).

[10] By 1900 music engravers were established in several hundred cities in the world, but the art of storing plates was usually concentrated with publishers.

There, every day thousands of pages are mechanically engraved onto rotogravure cylinders, typically a steel base with a copper layer of about 0.1 mm in which the image is transferred.

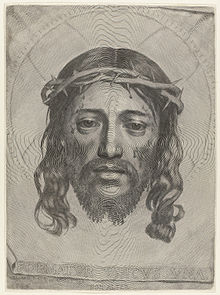

In traditional engraving, which is a purely linear medium, the impression of half-tones was created by making many very thin parallel lines, a technique called hatching.