Chandrayaan programme

The idea of a lunar scientific mission was first raised in 1999 during a meeting of the Indian Academy of Sciences (IAS) which was then carried forward by the Astronautical Society of India (ASI) in 2000.

It is whether we can afford to ignore it.On 15 August 2003, then prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee announced the project which was estimated to cost ₹350 crore (US$40 million).

[8][9] In November of the same year, the government approved the Chandrayaan project which would consist of an orbiter that would conduct mineralogical and chemical mapping of the surface.

[11] The MIP was planned to be dropped from 100 km (62 mi) altitude and would acquire close-range images of the surface, collect telemetry data for future soft landing missions and measure the constituents of the lunar atmosphere.

[21] However, an agreement had already been signed in the year 2007 by ISRO and Roscosmos, the Russian federal space agency, for the second lunar mission under the Chandrayaan-2 project.

[22] According to the agreement, ISRO had the responsibility of launching, orbiting, and deployment of the Pragyan rover while Russia's Roscosmos would provide the lander.

[28] With the Russian agreement falling apart, India was left alone and now had complete responsibility for the project including the development of lander technology.

According to the chairman K. Sivan, the lander was operating as expected until it was just 2.1 km (1.3 mi) above the surface when it started deviating from the intended trajectory.

[37] Four years later, ISRO chairman S. Somanath revealed three major reasons for the failure, the presence of five engines that generated a higher thrust which made the errors accumulate over time, the lander being unable to turn very fast because it was not expected to perform at such a high pace turning and the final reason was the small 500x500 m landing site chosen that left the lander with less room for error.

The Chandrayaan-3 would be a re-attempt to demonstrate the landing capabilities needed for the LUPEX mission, a proposed partnership with Japan that was planned for 2025-26 time frame.

[39] ISRO sought ₹75 crore (US$8.7 million) from the government as initial funding for the Chandrayaan-3 project that included a propulsion module, a lander, and a rover.

[48] Few more changes with strengthening the landing legs, improvisation in instruments, a failure-proof configuration and additional testing meant that the new schedule for the launch was moved to second quarter of 2023.

[49] In May 2023, the spacecraft was in its final stage of the assembly of payloads at the U R Rao Satellite Centre with the launch targeted for the first or second week of July.

[53] The Chandrayaan programme consists of robotic explorers such as the Moon Impact Probe (MIP) an impactor, Chandrayaan-1 and 2 the orbiters, Vikram lander and Pragyaan rover.

It carried a Radar altimeter to record the altitude data which would be used in qualifying technologies for future soft landing missions, a Video imaging system to acquire close-range pictures of the lunar surface, and a Mass spectrometer to study the tenuous atmosphere of the Moon.

[17] Chandrayaan-1 launched on 22 October 2008 aboard PSLV-XL was a solar-powered cuboid orbiter that weighed 1,380 kg (3,042 lb) along with the Moon Impact Probe.

Efforts such as rotating the craft by 20 degrees, shutting down the mission computers, and increasing its orbit to 200 km (120 mi) were made to bring its temperature down and to avoid damaging the onboard instruments.

[59] A year later, the overheating problem was responsible for ending the mission as it damaged the star sensors which maintained the orientation of craft.

The orientation was then barely maintained with the help of gyroscopes as a temporary measure before losing contact on 28 August 2009, which ended the mission a year before its intended duration.

Considering the estimated fuel availability and the safety to GEO spacecraft, the optimal Earth return trajectory was designed for October 2023.

[79] The initial descent and critical braking procedures went as intended but upon reaching 2.1 km (1.3 mi) altitude, the lander began deviating and lost its contact with the mission control after subsequent crash landing.

Coarse throttling of main engines, error in computing the remaining time in the mission and a small landing site of 500 x 500 m were the other reasons attributed to the failure.

[89] On 3 September 2023, before putting Vikram to sleep mode, ISRO conducted a hop on the lunar surface by firing its engines that moved it 40 cm (16 in) vertically as well as laterally before touching down again.

The hop experiment proved to be the most significant test conducted by ISRO as the data would aid in future sample return missions under the programme.

Unlike the lander, there were no changes made in the Pragyan rover except for switching ISRO's logo with Emblem of India on the left and right wheels respectively that would imprint them on the regolith.

[97] The samples returned from the equatorial region during Apollo programme failed to provide definitive evidence, reinforcing the need for research on the lunar poles.

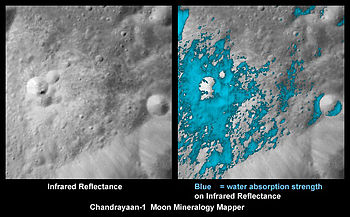

On 12 November 2008, the MIP separated from the Chandrayaan-1 orbiter and began its descent to the surface, during which it detected the clear presence of molecules with atomic mass unit 18 i.e., water.

In 2018, the data obtained from the M3 was used by the scientist at University of Hawaiʻi, Dr. Shuai Li and his team to research lunar water in the dark craters of the poles.

With successful demonstration in soft landing and roving, the programme then moved into its next phase where a rover with greater scientific payload is to be sent to conduct on-site sample analysis.

Each flight is designed to progressively expand India's capabilities in lunar exploration, potentially with the co-operation of all Artemis accords signatories.