Guajeo

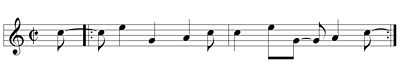

A guajeo (Anglicized pronunciation: wa-hey-yo) is a typical Cuban ostinato melody, most often consisting of arpeggiated chords in syncopated patterns.

Some musicians only use the term guajeo for ostinato patterns played specifically by a tres, piano, an instrument of the violin family, or saxophones.

The guajeo shares rhythmic, melodic and harmonic similarities with the short ostinato figures played on marimbas, lamellophones, and string instruments in sub-Saharan Africa.

Moore states: "Hip fans will often flaunt their knowledge by pointing out that the song was originally recorded by Tito Puente in 1963, and before that by Arcaño y sus Maravillas as "Chanchullo" in 1957, but it goes all the way back to Cachao's "Rareza de Melitón" in 1942.

The following example shows five different variants of a 2–3 trombone moña improvised by José Rodrígues on "Bilongo" (c. 1969), performed by Eddie Palmieri.

"Tanga" was initially a descarga (Cuban jam session) with jazz solos superimposed, spontaneously composed by Mario Bauzá at a rehearsal (May 29, 1943).

From jazz came a harmonic vocabulary based on extended harmonies of altered and unaltered ninths, elevenths and thirteenths, as well as quartal harmony—chords built on fourths.

[17]The chachachá can be thought of as a rare "de-Africanizing" step in Cuban popular music's trajectory in the mid-20th century because it involves unison singing, instead of call-and-response.

Although the term, dance step, and popular mania of chachachá took hold in 1951, its key musical elements were already in place in Arcaño's group of 1948, including Enrique Jorrín, the violinist‐composer who would later be credited as the "inventor" of the genre.

Mauleón makes the point that since the Cuban mozambique originally began in what was essentially a percussion ensemble with trombones, there is no set piano part for the rhythm.

It started as a dance craze, with the dancers mimicking the movement of stirring a vat of roasting coffee beans, but long after the dance had been relegated to the history of pop culture, the rhythm itself continued to influence the likes of José Luis "Changuito" Quintana of Los Van Van, Orlando Mengual of Charanga Habanera, Denis "Papacho" Savón of Issac Delgado, Tomás "El Panga" Ramos of Paulito FG and Cubanismo, and many Latin Jazz musicians—Moore.

Formell had been surreptitiously listening to forbidden North American and British pop music and used his new influences to create several hits in a new shockingly un-Cuban style.

Changüí '68 broke so many established rules that subsequent genres, including Formell's own songo, were free to reassemble the stylistic elements as they saw fit.

On "Con el bate de aluminio" (1979), the right hand plays steady onbeats, sounding a rock‐influenced imi – bVII – bVI chord progression.

[24] The Cuban jazz pianist Gonzalo Rubalcaba developed a technique of pattern and harmonic displacement in the 1980s, which was adopted into timba guajeos in the 1990s.

By adopting polyrhythmic elements from the son, the horns took on a vamp-like role similar to the piano montuno and tres (or string) guajeo"—Mauleón (1993: 155).

Moore states: "Pupy's arrangement pushes the envelope ... by expanding the violin part from the usual sparse rhythmic loop to a long and constantly varying melody, pitted against an almost equally inventive piano [guajeo].

The violin part is active and creative enough to stand alone as a mambo section, but it is used as the underpinning for an equally complex and interesting coro.

The unique style of R&B that emerged from New Orleans during this period played a pivotal role in the development of funk and the rock guitar riff.

[35] In the 1940s New Orleans pianist "Professor Longhair" (Henry Roeland Byrd) was playing with Caribbean musicians, listening a lot to Perez Prado's mambo records, and absorbing and experimenting with it all.

[38] Alexander Stewart states that Longhair was a key figure bridging the worlds of boogie woogie and the new style of rhythm and blues.

Tresillo, the habanera, and related African-based single-celled figures have long been heard in the left hand part of piano compositions by New Orleans musicians, for example—Louis Moreau Gottschalk ("Souvenirs From Havana" 1859), and Jelly Roll Morton ("The Crave" 1910).

In a related development, the underlying rhythms of American popular music underwent a basic, yet generally unacknowledged transition from triplet or shuffle feel to even or straight eighth notes.

[42] Concerning funk motifs, Stewart states: "This model, it should be noted, is different from a time line (such as clave and tresillo) in that it is not an exact pattern, but more of a loose organizing principle.

"[46]Banning Eyre distills down the Congolese guitar style to this skeletal figure, where clave is sounded by the bass notes (notated with downward stems).

Eventually they created their own original Cuban-like compositions, with lyrics sung in French or Lingala, a lingua franca of the western Congo region.

[50] Some African guitar genres such as Zimbabwean chimurenga (created by Thomas Mapfumo), are a direct adaptation of traditional ostinatos, in this case mbira music.

[51] In a densely textured seben section of a soukous song (below), the three interlocking guitar parts are reminiscent of the Cuban practice of layering guajeos.

[55] The Nigerian multi-instrumentalist and bandleader Fela Kuti, who gave it its name,[55] used it to revolutionise musical structure as well as the political context in his native Nigeria.

John Storm Roberts states: "It was the Cuban connection ... that provided the major and enduring influences—the ones that went deeper than earlier imitation or passing fashion.