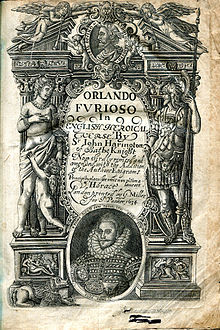

Orlando Furioso

Many themes are interwoven in its complicated episodic structure, but the most important are the paladin Orlando's unrequited love for the pagan princess Angelica, which drives him mad; the love between the female Christian warrior Bradamante and the Saracen Ruggiero, who are supposed to be the ancestors of Ariosto's patrons, the House of Este of Ferrara; and the war between Christian and Infidel.

[4] The poem is divided into forty-six cantos, each containing a variable number of eight-line stanzas in ottava rima (a rhyme scheme of abababcc).

Ottava rima had been used in previous Italian romantic epics, including Luigi Pulci's Morgante and Boiardo's Orlando Innamorato.

Ariosto continued to write more material for the poem and in the 1520s he produced five more cantos, marking a further development of his poetry, which he decided not to include in the final edition.

Ariosto had sought stylistic advice from the humanist Pietro Bembo to give his verse the last degree of polish and this is the version known to posterity.

[10] In Orlando Furioso, instead of the chivalric ideals which were no longer current in the 16th century, a humanistic conception of man and life is vividly celebrated under the appearance of a fantastical world, notwithstanding his early modern approaches to feminism.

[11] The action of Orlando Furioso takes place against the background of the war between the Christian emperor Charlemagne and the Saracen king of Africa, Agramante [it; la], who has invaded Europe to avenge the death of his father Troiano.

Meanwhile, Orlando, Charlemagne's most famous paladin, has been tempted to forget his duty to protect the emperor because of his love for the pagan princess Angelica.

When Orlando learns the truth, by finding the pair's secret garden of love, or Locus Amoenus, he goes mad with despair and rampages through Europe and Africa destroying everything in his path, and thus demonstrates the frenzy that the title suggests.

He also has to avoid the enchantments of his foster father, the wizard Atlante, who does not want him to fight or see the world outside of his iron castle, because looking into the stars it is revealed that if Ruggiero converts himself to Christianity, he will die.

In chapter 11 of Sir Walter Scott's novel Rob Roy published in 1817, but set circa 1715, Mr. Francis Osbaldistone talks of completing "my unfinished version of Orlando Furioso, a poem which I longed to render into English verse...".

[22] The English novelist Anthony Powell's Hearing Secret Harmonies includes images from Orlando Furioso to open chapter two.

The Castle of Iron, a fantasy novel by L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt, takes place in the "universe" of Orlando Furioso.

The enthusiasm for operas based on Ariosto continued into the Classical era and beyond with such examples as Johann Adolph Hasse’s Il Ruggiero (1771), Niccolò Piccinni's Roland (1778), Haydn's Orlando paladino (1782), Méhul's Ariodant (1799) and Simon Mayr's Ginevra di Scozia (1801).

[24] Orlando Furioso has been the inspiration for many works of art, including paintings by Eugène Delacroix, Tiepolo, Ingres, Redon, and a series of illustrations by Gustave Doré.

Luzatti's original verse story in Italian is about the plight of a beautiful maiden called Biancofiore – White Flower, or Blanchefleur – and her brave hero, Captain Rinaldo, and Ricardo and his paladins – the term used for Christian knights engaged in Crusades against the Saracens and Moore.

The catalyst for victory is the good magician, Urlubulu, who lives in a lake, and flies through the air on the back of his magic blue bird.

In 2014, Enrico Maria Giglioli created Orlando's Wars: lotta tra cavalieri, a trading card game with characters and situations of the poem, divided in four categories: Knight, Maiden, Wizard and Fantastic Creature.

Around the middle of the 16th century, some Italian critics such as Gian Giorgio Trissino complained that the poem failed to observe the unity of action as defined by Aristotle, by having multiple plots rather than a single main story.

[27] Ariosto's defenders, such as Giovanni Battista Giraldi, replied that it was not a Classical epic but a romanzo, a genre unknown to Aristotle; therefore his standards were irrelevant.

In the 19th century, Hegel considered that the work's many allegories and metaphors did not serve merely to refute the ideal of chivalry, but also to demonstrate the fallacy of human senses and judgment.

[35] A comparison of the original text of Book 1, Canto 1 with various translations into English is given in the following table: Le donne, i cavallier, l'arme, gli amori Le cortesie, l'audaci imprese io canto; Che furo al tempo, che passaro i Mori D'Africa il mare, e in Francia nocquer tanto; Seguendo l'ire, e i giovenil furori D'Agramante lor Re, che si diè vanto Di vendicar la morte di Troiano Sopra Re Carlo Imperador Romano.

Of Dames, of Knights, of armes, of loues delight, Of courtesies, of high attempts I speake, Then when the Moores transported all their might On Affrick seas the force of France to breake: Drawne by the youthfull heate and raging spite, Of Agramant their king, that vowd to wreake The death of King Trayana (lately slayne) Vpon the Romane Emperour Charlemaine.

Of Dames, of Knights, of armes, of loves delight, Of courtesies, of high attempts I speake, Then when the Moores transported all their might On Africke seas, the force of France to breake: Incited by the youthfull heate and spight Of Agramant their king, that vow'd to wreake The death of King Trayano (lately slaine) Vpon the Romane Emperour Charlemaine.

Of ladies, cavaliers, of arms and love, Their courtesies, their bold exploits, I sing, When over Afric's sea the Moor did move, On France's realm such ruin vast to bring; While they the youthful ire and fury strove Of Agramant to follow, boastful King, That of Trojano he'd revenge the doom, On Charlemain, the Emperor of Rome.

What time the Moors from Afric's hostile strand Had crost the seas to ravage Gallia's land, By Agramant, their youthful monarch, led In deep resentment for Troyano dead, With threats on Charlemain t'avenge his fate, Th'imperial guardian of the Roman state.

OF LOVES and LADIES, KNIGHTS and ARMS, I sing, Of COURTESIES, and many a DARING FEAT; And from those ancient days my story bring, When Moors from Afric passed in hostile fleet, And ravaged France, with Agramant their king, Flushed with his youthful rage and furious heat; Who on king Charles', the Roman emperor's head Had vowed due vengeance for Troyano dead.

Of ladies, cavaliers, of love and war, Of courtesies and of brave deeds I sing, In times of high endeavour when the Moor Had crossed the seas from Africa to bring Great harm to France, when Agramante swore In wrath, being now the youthful Moorish king, To avenge Troiano, who was lately slain, Upon the Roman Emperor Charlemagne.

Of ladies, knights, of passions and of wars, of courtliness, and of valiant deeds I sing that took place in that era when the Moors crossed the sea from Africa to bring such troubles to France.