Characteristic impedance

The characteristic impedance or surge impedance (usually written Z0) of a uniform transmission line is the ratio of the amplitudes of voltage and current of a wave travelling in one direction along the line in the absence of reflections in the other direction.

Equivalently, it can be defined as the input impedance of a transmission line when its length is infinite.

The characteristic impedance of a lossless transmission line is purely real, with no reactive component (see below).

A transmission line of finite length (lossless or lossy) that is terminated at one end with an impedance equal to the characteristic impedance appears to the source like an infinitely long transmission line and produces no reflections.

is the ratio of the voltage and current of a pure sinusoidal wave of the same frequency travelling along the line.

Generally, a wave is reflected back along the line in the opposite direction.

When the reflected wave reaches the source, it is reflected yet again, adding to the transmitted wave and changing the ratio of the voltage and current at the input, causing the voltage-current ratio to no longer equal the characteristic impedance.

This new ratio including the reflected energy is called the input impedance of that particular transmission line and load.

A surge of energy on a finite transmission line will see an impedance of

The voltage and current phasors on the line are related by the characteristic impedance as:

where the subscripts (+) and (−) mark the separate constants for the waves traveling forward (+) and backward (−).

doing so is functionally equivalent of solving for the Fourier coefficients for voltage and current amplitudes, at some fixed angular frequency

And for typical transmission lines, that are carefully built from wire with low loss resistance

in the exponential solutions of the equation, similar to the time-dependent part

In order to be compatible, they must still satisfy the original differential equations, one of which is

and combining identical powers, we see that in order for the above equation to hold for all possible values of

defined in the above equations has the dimensions of impedance (ratio of voltage to current) and is a function of primary constants of the line and operating frequency.

It is called the “characteristic impedance” of the transmission line, and conventionally denoted by

Manufacturers make commercial cables to approximate this condition very closely over a wide range of frequencies.

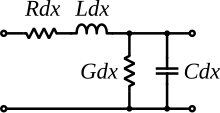

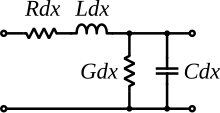

Consider an infinite ladder network consisting of a series impedance

Its solution is: For a transmission line, it can be seen as a limiting case of an infinite ladder network with infinitesimal impedance and admittance at a constant ratio.

[6][4][5] Taking the positive root, this equation simplifies to: Using this insight, many similar derivations exist in several books[6][4][5] and are applicable to both lossless and lossy lines.

For a lossless line, R and G are both zero, so the equation for characteristic impedance derived above reduces to:

The above expression is wholly real, since the imaginary term j has canceled out, implying that

The solutions to the long line transmission equations include incident and reflected portions of the voltage and current:

When the line is terminated with its characteristic impedance, the reflected portions of these equations are reduced to 0 and the solutions to the voltage and current along the transmission line are wholly incident.

Their magnitudes remain constant along the length of the line and are only rotated by a phase angle.

The characteristic impedance of coaxial cables (coax) is commonly chosen to be 50 Ω for RF and microwave applications.

Coax for video applications is usually 75 Ω for its lower loss.

This article incorporates public domain material from Federal Standard 1037C.