Characteristica universalis

Many Leibniz scholars writing in English seem to agree that he intended his characteristica universalis or "universal character" to be a form of pasigraphy, or ideographic language.

Others, such as Jaenecke, for example, have observed that Leibniz also had other intentions for the characteristica universalis, and these aspects appear to be a source of the aforementioned vagueness and inconsistency in modern interpretations.

According to Jaenecke, the Leibniz project is not a matter of logic but rather one of knowledge representation, a field largely unexploited in today's logic-oriented epistemology and philosophy of science.

It is precisely this one-sided orientation of these disciplines, which is responsible for the distorted picture of Leibniz's work found in the literature.As Louis Couturat wrote, Leibniz criticized the linguistic systems of George Dalgarno and John Wilkins for this reason since they focused on ...practical uses rather than scientific utility, that is, for being chiefly artificial languages intended for international communication and not philosophical languages that would express the logical relations of concepts.

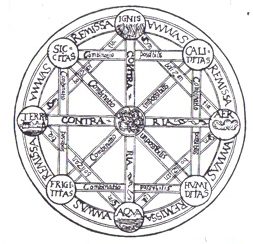

He favors, and opposes to them, the true "real characteristic", which would express the composition of concepts by the combination of signs representing their simple elements, such that the correspondence between composite ideas and their symbols would be natural and no longer conventional.Leibniz said that his goal was an alphabet of human thought, a universal symbolic language (characteristic) for science, mathematics, and metaphysics.

In the domain of science, Leibniz aimed for his characteristica to form diagrams or pictures, depicting any system at any scale, and understood by all regardless of native language.

Leibniz talked about his dream of a universal scientific language at the very dawn of his career, as follows: We have spoken of the art of complication of the sciences, i.e., of inventive logic...

If these are correctly and ingeniously established, this universal writing will be as easy as it is common, and will be capable of being read without any dictionary; at the same time, a fundamental knowledge of all things will be obtained.

Their pictures, however, are not reduced to a fixed alphabet... with the result that a tremendous strain on the memory is necessary, which is the contrary of what we propose.Nicholas Rescher, reviewing Cohen's 1954 article, wrote that: Leibniz's program of a universal science (scientia universalis) for coordinating all human knowledge into a systematic whole comprises two parts: (1) a universal notation (characteristica universalis) by use of which any item of information whatever can be recorded in a natural and systematic way, and (2) a means of manipulating the knowledge thus recorded in a computational fashion, so as to reveal its logical interrelations and consequences (the calculus ratiocinator).Near the end of his life, Leibniz wrote that combining metaphysics with mathematics and science through a universal character would require creating what he called: ... a kind of general algebra in which all truths of reason would be reduced to a kind of calculus.

It would be very difficult to form or invent this language or characteristic, but very easy to learn it without any dictionaries.The universal "representation" of knowledge would therefore combine lines and points with "a kind of pictures" (pictographs or logograms) to be manipulated by means of his calculus ratiocinator.

In a March 1706 letter to the Electress Sophia of Hanover, the spouse of his patron, he wrote: It is true that in the past I planned a new way of calculating suitable for matters which have nothing in common with mathematics, and if this kind of logic were put into practice, every reasoning, even probabilistic ones, would be like that of the mathematician: if need be, the lesser minds which had application and good will could, if not accompany the greatest minds, then at least follow them.

But I do not know if I will ever be in a position to carry out such a project, which requires more than one hand; and it even seems that mankind is still not mature enough to lay claim to the advantages which this method could provide.In another 1714 letter to Nicholas Remond, he wrote: I have spoken to the Marquis de l'Hôpital and others about my general algebra, but they have paid no more attention to it than if I had told them about a dream of mine.

Although most logistic is either founded upon or makes large use of the principles of symbolic logic, still a science of order in general does not necessarily presuppose or begin with symbolic logic.Following from this Cohen stipulated that the universal character would have to serve as: These criteria together with the notion of logistic reveal that Cohen and Lewis both associated the characteristica with the methods and objectives of general systems theory.

In this vein, Parkinson wrote: Leibniz's views about the systematic character of all knowledge are linked with his plans for a universal symbolism, a Characteristica Universalis.

The ideal now seems absurdly optimistic..."The logician Kurt Gödel, on the other hand, believed that the characteristica universalis was feasible, and that its development would revolutionize mathematical practice (Dawson 1997).

It appears that Gödel assembled all of Leibniz's texts mentioning the characteristica, and convinced himself that some sort of systematic and conspiratorial censoring had taken place, a belief that became obsessional.