Charles Bonnet

Charles Bonnet (French pronunciation: [ʃaʁl bɔnɛ]; 13 March 1720 – 20 May 1793) was a Genevan[a] naturalist and philosophical writer.

[3] The last twenty five years of his life he spent quietly in the country, at Genthod, near Geneva, where he died after a long and painful illness on 20 May 1793.

The account of the ant-lion in Noël-Antoine Pluche's Spectacle de la nature, which he read in his sixteenth year, turned his attention to insect life.

[5] In 1741, Bonnet began to study reproduction by fusion and the regeneration of lost parts in the freshwater hydra and other animals; and in the following year he discovered that the respiration of caterpillars and butterflies is performed by pores, to which the name spiracles has since been given.

In 1743, he was admitted a fellow of the Royal Society; and in the same year he became a doctor of laws—his last act in connection with a profession which had ever been distasteful to him.

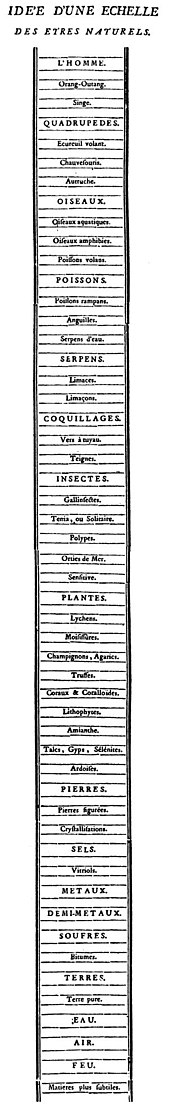

[6] His first published work appeared in 1745, entitled Traité d'insectologie, in which were collected his various discoveries regarding insects, along with a preface on the development of germs and the scale of organized beings.

This was followed by the Essai analytique sur les facultés de l'âme (Analytical essay on the faculties of the soul) (Copenhagen, 1760), in which he develops his views regarding the physiological conditions of mental activity.

He returned to physical science, but to the speculative side of it, in his Considerations sur les corps organisées (Amsterdam, 1762), designed to refute the theory of epigenesis, and to explain and defend the doctrine of pre-existent germs.

He documented it in his 87-year-old grandfather,[8] who was nearly blind from cataracts in both eyes but perceived men, women, birds, carriages, buildings, tapestries and scaffolding patterns.

The divine Being originally created a multitude of germs in a graduated scale, each with an inherent power of self-development [citation needed].

[4] In this final proposition, Bonnet violates his own principle of continuity, by postulating an interval between the highest created being and the Divine[citation needed].