History of evolutionary thought

Alternatives to natural selection suggested during "the eclipse of Darwinism" (c. 1880 to 1920) included inheritance of acquired characteristics (neo-Lamarckism), an innate drive for change (orthogenesis), and sudden large mutations (saltationism).

Following the establishment of evolutionary biology, studies of mutation and genetic diversity in natural populations, combined with biogeography and systematics, led to sophisticated mathematical and causal models of evolution.

[19] The Roman Skeptic philosopher Cicero wrote that Zeno was known to have held the view, central to Stoic physics, that nature is primarily "directed and concentrated...to secure for the world...the structure best fitted for survival.

[20] In line with earlier Greek thought, the third-century Christian philosopher and Church Father Origen of Alexandria argued that the creation story in the Book of Genesis should be interpreted as an allegory for the falling of human souls away from the glory of the divine, and not as a literal, historical account:[25][26] For who that has understanding will suppose that the first, and second, and third day, and the evening and the morning, existed without a sun, and moon, and stars?

And if God is said to walk in the paradise in the evening, and Adam to hide himself under a tree, I do not suppose that anyone doubts that these things figuratively indicate certain mysteries, the history having taken place in appearance, and not literally.Gregory of Nyssa wrote:Scripture informs us that the Deity proceeded by a sort of graduated and ordered advance to the creation of man.

[35][36] Henry Fairfield Osborn wrote in From the Greeks to Darwin (1894): If the orthodoxy of Augustine had remained the teaching of the Church, the final establishment of Evolution would have come far earlier than it did, certainly during the eighteenth instead of the nineteenth century, and the bitter controversy over this truth of Nature would never have arisen.

Plainly as the direct or instantaneous Creation of animals and plants appeared to be taught in Genesis, Augustine read this in the light of primary causation and the gradual development from the imperfect to the perfect of Aristotle.

[37]In A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (1896), Andrew Dickson White wrote about Augustine's attempts to preserve the ancient evolutionary approach to the creation as follows: For ages a widely accepted doctrine had been that water, filth, and carrion had received power from the Creator to generate worms, insects, and a multitude of the smaller animals; and this doctrine had been especially welcomed by St. Augustine and many of the fathers, since it relieved the Almighty of making, Adam of naming, and Noah of living in the ark with these innumerable despised species.

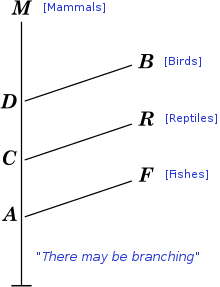

[54] Later in the 18th century, the French philosopher Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, one of the leading naturalists of the time, suggested that what most people referred to as species were really just well-marked varieties, modified from an original form by environmental factors.

Buffon's works, Histoire naturelle (1749–1789) and Époques de la nature (1778), containing well-developed theories about a completely materialistic origin for the Earth and his ideas questioning the fixity of species, were extremely influential.

[55][56] Another French philosopher, Denis Diderot, also wrote that living things might have first arisen through spontaneous generation, and that species were always changing through a constant process of experiment where new forms arose and survived or not based on trial and error; an idea that can be considered a partial anticipation of natural selection.

[57] Between 1767 and 1792, James Burnett, Lord Monboddo, included in his writings not only the concept that man had descended from primates, but also that, in response to the environment, creatures had found methods of transforming their characteristics over long time intervals.

One of the French scientists who influenced Grant was the anatomist Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, whose ideas on the unity of various animal body plans and the homology of certain anatomical structures would be widely influential and lead to intense debate with his colleague Georges Cuvier.

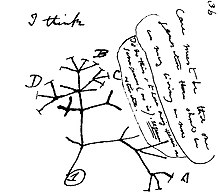

Darwin would make good use of the homologies analyzed by Owen in his own theory, but the harsh treatment of Grant, and the controversy surrounding Vestiges, showed him the need to ensure that his own ideas were scientifically sound.

As an example, Loren Eiseley has found isolated passages written by Buffon suggesting he was almost ready to piece together a theory of natural selection, but states that such anticipations should not be taken out of the full context of the writings or of cultural values of the time which made Darwinian ideas of evolution unthinkable.

"[85] Darwin was influenced by Charles Lyell's ideas of environmental change causing ecological shifts, leading to what Augustin de Candolle had called a war between competing plant species, competition well described by the botanist William Herbert.

Darwin's hypothesis of pangenesis, while relying in part on the inheritance of acquired characteristics, proved to be useful for statistical models of evolution that were developed by his cousin Francis Galton and the "biometric" school of evolutionary thought.

[105] Charles Darwin was aware of the severe reaction in some parts of the scientific community against the suggestion made in Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation that humans had arisen from animals by a process of transmutation.

By the early 1860s, as summarized in Charles Lyell's 1863 book Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man, it had become widely accepted that humans had existed during a prehistoric period—which stretched many thousands of years before the start of written history.

[109] Richard Owen vigorously defended the classification suggested by Georges Cuvier and Johann Friedrich Blumenbach that placed humans in a separate order from any of the other mammals, which by the early 19th century had become the orthodox view.

[115][116] The American biologist Sewall Wright, who had a background in animal breeding experiments, focused on combinations of interacting genes, and the effects of inbreeding on small, relatively isolated populations that exhibited genetic drift.

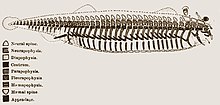

[115][116][120] In the 1944 book Tempo and Mode in Evolution, George Gaylord Simpson showed that the fossil record was consistent with the irregular non-directional pattern predicted by the developing evolutionary synthesis, and that the linear trends that earlier paleontologists had claimed supported orthogenesis and neo-Lamarckism did not hold up to closer examination.

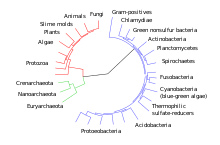

In the early 1960s, biochemists Linus Pauling and Emile Zuckerkandl proposed the molecular clock hypothesis (MCH): that sequence differences between homologous proteins could be used to calculate the time since two species diverged.

Established evolutionary biologists—particularly Ernst Mayr, Theodosius Dobzhansky, and George Gaylord Simpson, three of the architects of the modern synthesis—were extremely skeptical of molecular approaches, especially their connection (or lack thereof) to natural selection.

[131][132] Contrary to the expectations of the Red Queen hypothesis, Hanley et al. found that the prevalence, abundance and mean intensity of mites was significantly higher in sexual geckos than in asexuals sharing the same habitat.

[133] Furthermore, Parker, after reviewing numerous genetic studies on plant disease resistance, failed to find a single example consistent with the concept that pathogens are the primary selective agent responsible for sexual reproduction in their host.

There was a renewal of structuralist themes in evolutionary biology in the work of biologists such as Brian Goodwin and Stuart Kauffman,[165] which incorporated ideas from cybernetics and systems theory, and emphasized the self-organizing processes of development as factors directing the course of evolution.

[177][178][179][180] Pierre Teilhard de Chardin's metaphysical Omega Point theory, found in his book The Phenomenon of Man (1955),[181] describes the gradual development of the universe from subatomic particles to human society, which he viewed as its final stage and goal, a form of orthogenesis.

The mathematical biologist Stuart Kauffman suggested that self-organization may play roles alongside natural selection in three areas of evolutionary biology: population dynamics, molecular evolution, and morphogenesis.

[165] However, Kauffman does not take into account the essential role of energy in driving biochemical reactions in cells, as proposed by Christian de Duve and modelled mathematically by Richard Bagley and Walter Fontana.